Maybe not much of a headline: Gay Man Excited that Gay Music Remains Gay, but here we are. This weekend, audiences stormed the Emerald City to make Wicked: Part One the third biggest opening of the year—and the largest opening for a movie musical ever. It’s a classic four-quadrant hit: youngs, olds, gals, and gays. My screening was wall-to-wall witch costumes, BFAs, and queer people breathing a collective sigh of relief. To paraphrase Jennifer Garner in Love, Simon: “You get to exhale now, gays.” Wicked is here, and it’s still very, very queer.

Based on Gregory Maguire’s novel Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West, Wicked: Part One follows Elphaba, a magically inclined outcast at Shiz University, and G(a)linda, a nepo baby hiding her mean streak behind hair tosses, on their journeys to becoming the Wicked Witch of the West and Glinda the Good, respectively. At school, Elphaba and Glinda go from frenemies to besties (as so many do), squabble over a boy (as is so often the case), and ultimately forge divergent paths: Elphaba as the villainized rebel against Oz’s oppressive Wizard and Glinda as a political pawn.

The story of Wicked has become a resonant allegory for many marginalized communities, particularly the LGBTQ+. Elphaba’s story is one of “othering,” as she’s ostracized for traits she cannot, will not, and should not change about herself (the casting of queer, Black Cynthia Ervico in the role only underlines these themes).

Meanwhile the plight of the animals of Oz echoes systemic, government oppression which may hit a little hard folks preparing to dodge post-election small talk with relatives during the holidays. Wicked is also about finding a way to live with your annoying roommate—which isn’t exclusively gay but is somehow very queer-relatable.

The Curse of De-Queering: Lessons from Into the Woods and Beyond

Ten years ago, the Into the Woods adaptation was a glaring example of what can go wrong when trying to simplify a complex Broadway adaptation on the road to the silver screen. Onstage, Stephen Sondheim and James Lapine’s Into the Woods is a dissection of fairy tales, featuring Rapunzel’s death, the Baker’s Wife’s affair with Prince Charming, and Little Red Riding Hood’s sexual awakening thanks to the Wolf. The Disney adaptation neutered it: Rapunzel simply disappears, the affair is watered down to a kiss, and the Wolf is reduced to something akin to a drunk uncle making his niece uncomfortable at her bat mitzvah.

Other adaptations have been even more explicit in erasing queerness, and the Disney live-action remakes have led the charge, stripping that queer subtext from its villains. Melissa McCarthy’s Ursula in The Little Mermaid is serviceable but lacks the camp menace of the Divine-inspired original. Scar’s queening-out is gone in The Lion King, and while Marwan Kenzari’s Jafar in Aladdin is distractingly hot, he doesn’t bring the manic gay energy of his animated counterpart.

Even The Prom, a musical explicitly about queer empowerment, fumbled its adaptation by casting James Corden in a widely criticized performance as a flamboyant gay man. There are lots of problems with The Prom, but laying them all at Corden’s feet somehow feels justified. Even for a musical as difficult to “butch up” as Wicked, the fears that it might suffer the same fate as some of these previous adaptations were very real.

The Queer Triumph of Wicked: Part One

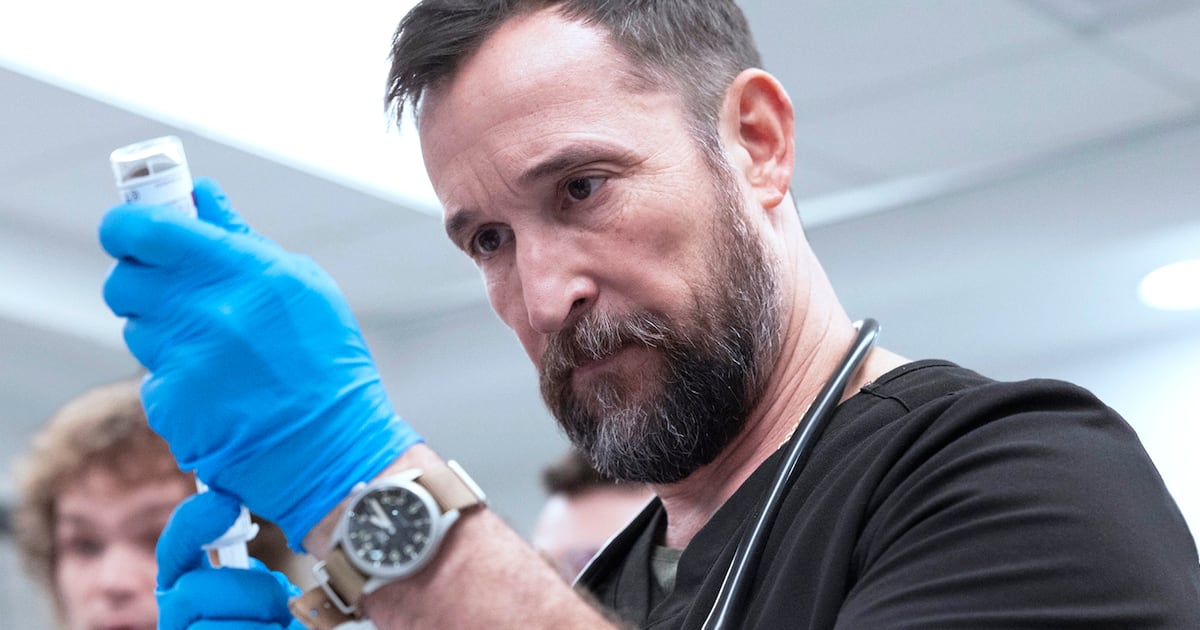

Instead, Wicked: Part One leans fully into its queerness. Cynthia Erivo plays Elphaba; Jonathan Bailey, an openly gay actor, takes on Fiyero; and Bowen Yang steals scenes as Glinda’s sidekick, Pfannee. Unlike Beauty and the Beast’s infamous “exclusive gay moment” for LeFou, Pfannee isn’t an ambiguously feminine prop—he’s a proper gay man in a skirted school uniform who reacts to Fiyero exactly as he should: “You can do anything to me,” Pfannee says upon meeting him. Same, girl, same.

Bailey’s Fiyero exudes “bisexual energy,” as Yang aptly described it on Las Culturistas. After seeing the film It’s not just an energy he’s exuding, Fiyero has known the touch of a man. Director Jon M. Chu leans into this, shooting Bailey with a seductive gaze that objectifies him in the most knowing way. Fiyero comes in to seduce everyone with glances, touches, and winks. No one is safe: Not you, Glinda; not you, Elphaba; not you, the horse Fiyero rode in on; not you, the lucky extra who has his face caressed by Jonathan Bailey. We have a Bisexual King on our hands, everyone, and I am thrilled to see it.

The film’s queerness extends to its world-building. Shiz University and the Emerald City are spaces where queer people simply exist. Background actors of all genders respond to Fiyero with genuine thirst, and the Oz Dust Ballroom is filled by men with beat mugs who are dressed to the gods. These details shouldn’t feel radical, but in tent-pole adaptations where queerness is often sanded down, they feel bold.

(This is to say nothing of Michelle Yeoh dressed in full-on drag in every scene, mean and wonderful, looking like she’s about to walk the runway for a Night of 1,000 Marie Antoinettes on Drag Race. “Icon” is an often overused label, but not when referring to this Queen!)

It would be irresponsible to discuss Wicked without the central queerness of the relationship between Glinda and Elphaba. Their relationship has launched a thousand ’ships and countless pieces of fan fiction. The chemistry between Erivo and Grande in the first half of the film is electric, crackling with tension—part rivalry, part lust; They want to wand each other’s brains out. As the film progresses, that chemistry becomes tender and romantic, landing somewhere between love and friendship.

Grande herself said she believes Glinda “might be a little in the closet” and Cynthia Erivo calling Elphaba and Glinda’s bond “true love.” FWIW, the OG Glinda, Kristen Chenoweth, backs them up. Who are we to argue? It’s a reminder that queer love stories don’t have to be overt to be impactful.

Why Wicked Being Queer Matters

Queer audiences have long sought representation in mainstream media, claiming everything from the Pigeon Lady in Home Alone 2 and the Babadook to Star Wars stormtroopers and the Green M&M. Go on Bluesky any day of the week, you’ll find someone saying: “Yes, she ate the house down boots! Queer icon!” and it’s, like, a background animated character from a 1996 episode of Nickelodeon’s Doug. But with Wicked, there’s no need to squint. The queerness is baked into its DNA—from the casting to the storytelling to the aesthetic choices.

And yet, the online discourse has been as wild as you’d expect. A now-viral clip features an interviewer earnestly telling Cynthia Erivo that “people are holding space for your rendition of Defying Gravity.” Erivo reacts in a way that is so theater kid, clutching her chest, eyes immediately dotted with tears, it may be the clearest form of representation the film has to offer. Not to be outdone, Twitter and TikTok are alight with posts debating whether Grande’s Glinda has the “right vibrato” and analyzing if Jonathan Bailey’s butt got enough screen time. (Spoiler: it could never.)

The only way the stakes on social media could be higher is if Wicked were a dress that is either blue and black or gold and white. These are the kinds of debates that will live on in gay bars for the next 20 years. And we’re already holding space for it.