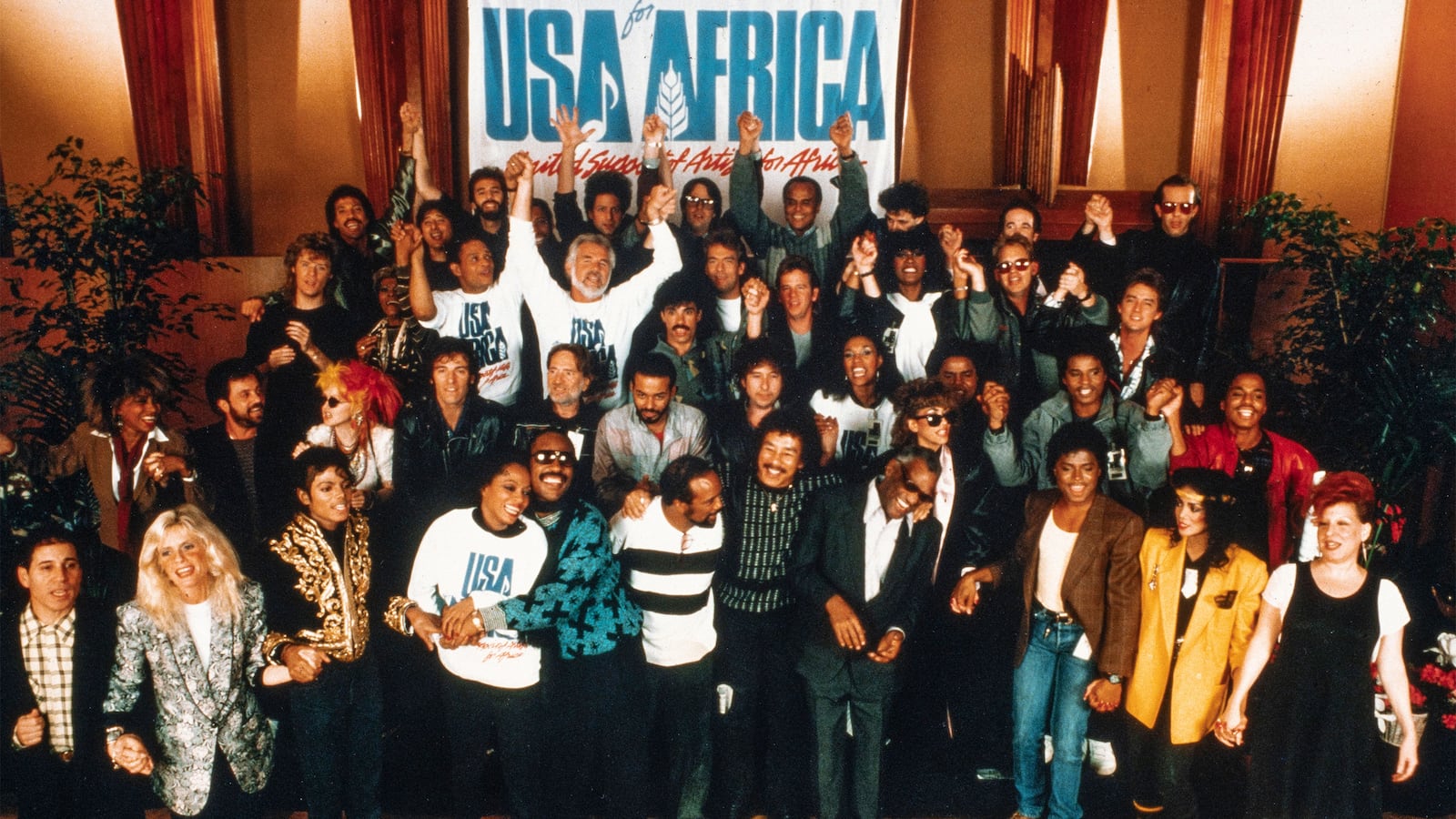

PARK CITY, Utah—A history lesson for any millennial or Gen-Z music fan who might think “We Are the World” is that 2010 abomination spearheaded by Wyclef Jean, The Greatest Night in Pop (which premiered Jan. 19 at the Sundance Film Festival, ahead of its Jan. 29 bow on Netflix) is a nostalgic look back at the creation of the insanely popular and well-known 1985 charity single. Featuring copious behind-the-scenes footage as well as the participation of many song contributors, Bao Nguyen’s documentary doesn’t strive to make the same transformative impact as its subject. Still, as far as celebratory backward glances go, it’s compelling enough to temporarily brighten one’s day.

"Nothing will ever be the same after tonight,” proclaimed Lionel Richie on stage at the American Music Awards on Jan. 28, 1985, and while that may not have been technically true, it was certainly a monumental evening for the recording artist. Tasked with hosting the televised awards gala, Richie also won a boatload of trophies, thereby establishing himself as a solo artist in his own right (this, after he’d left the Commodores) and cementing his standing as one of the decade’s Billboard kings. Richie discusses the overwhelming insanity of that production in The Greatest Night in Pop, albeit only in the context of his genuine triumph: organizing the after-show get-together at A&M Recording Studios in Hollywood where he, his manager Ken Kragen, producer Quincy Jones, and superstar Michael Jackson assembled a who’s-who of the pop-music universe.

The impetus for that gathering was “We Are the World,” a ditty designed as a fundraising tool for African famine relief. Inspired by Harry Belafonte, who himself was motivated by Bob Geldof’s Band Aid single “Do They Know It’s Christmas?”, the song was intended as an unparalleled chart-topper. From the start, however, there were problems. At the front of that line was the fact that wrangling disparate luminaries was a logistical nightmare. The solution, it turned out, was to record the song in a single night, immediately after the American Music Awards, since so many hit-makers would already be in one Los Angeles location. Just as pressing an issue, though, was the tune itself, which Richie and Jackson furiously wrote on deadline, this after Stevie Wonder—whom Richie initially tried to enlist—failed to return his calls.

Even without Wonder’s assistance, Richie and Jackson turned around a song that wowed Jones, and demos were swiftly sent to potential collaborators with a note that cryptically refused to reveal the recording’s location—a measure that Kragen believed was necessary in order to keep paparazzi at bay and, thus, to encourage artists to attend.

As history proved, many did, from Bob Dylan, Tina Turner, and Kenny Rogers to Diana Ross, Billy Joel, and Al Jarreau, who apparently struggled to complete his brief solo due to excessive wine consumption. Quite a few “We Are the World” A-listers chime in with fond remembrances in The Greatest Night in Pop, including Bruce Springsteen, Dionne Warwick, Smokey Robinson, Cyndi Lauper, Kenny Loggins, and Huey Lewis. None of them have anything revelatory to say about the proceedings other than what a thrill and honor it was to be in the same room with these amazingly talented individuals, and aside from Sheila E. bitterly admitting that she was only invited in order to lure Prince to the studio. Yet their commentary lends the material requisite mega-watt personality.

Despite boasting brief audio snippets of Richie and Jackson writing “We Are the World”—complemented by Richie remembering his run-ins with Jackson’s pet snake and chimp BFF Bubbles—The Greatest Night in Pop works best in its back half by situating viewers inside the recording studio where the project’s numerous musicians congregated. Anyone who’s seen the song’s music video will know this space well, since that too was filmed on this important occasion, although there are plentiful never-before-seen outtakes of these men and women toiling away on the track. Witnessing legends invent in real-time, quarrel, and nervously prepare and perform, each one eager to not look like they don’t belong—a situation with which Lewis had to contend when asked to develop an on-the-fly three-part harmony with Lauper and Kim Carnes—is arguably the reason for this documentary’s existence.

The Greatest Night in Pop is a chance to spend time in VIP company, and its best moments are its glimpses at these 46 greats figuring out ways to blend their singular skills, as when Wonder takes Dylan aside to help the latter nail his part—a process that entails Wonder doing a spot-on impersonation of the folk icon. In fact, those are just about all that the film has going for it, since Nguyen eschews any serious discussion about the charity aspect of the song; where the money went, and what difference it made, are left to closing text cards that keep things vague and uplifting. The focus is squarely on watching stars create globally popular art by the seat of their pants, and that turns out to be moderately compelling, whether it’s Jackson workshopping lyrics and melodies mere hours before the rest of his illustrious compatriots arrive at the studio, or Rogers and Paul Simon working to make their voices properly mesh.

Nguyen keeps the late Jackson and now-90-year-old Jones in the foreground throughout, highlighting the chief roles they played in accomplishing this groundbreaking achievement. Nonetheless, at the center of The Greatest Night in Pop is Richie, who certainly did it all over the course of 24 hours on Jan. 28, 1985, and who still seems blown away by the fact that they pulled off this all-nighter feat with such success (“We Are the World” is presently the eighth best-selling single of all time). Richie turns out to be a gregarious chronicler of his own story, which ultimately suggests that musicians are attracted to (and in awe of) other musicians as much as they are to noble causes. All that’s missing from this spirited if superficial rewind, then, is an answer to the greatest question regarding “We Are the World”: Who the hell invited Dan Aykroyd?