Universal Language opens with a spectacle of hilarious inappropriateness.

In a classroom in a fantastical Winnipeg where residents speak both French and Farsi, teacher Iraj Bilodeau (Mani Soleymanlou) enters late to find his students misbehaving. With comical fury, he lambastes these “creatures” for their conduct and, once the lesson begins, continues his censure on an individual basis, be it directed at a boy dressed as Groucho Marx (“Your face is disgusting to others. Go stand in the closet”) or Omid (Sobhan Javadi), who has “below-average intelligence,” is “blind as a bat,” and whose excuse for not having his glasses is that they were stolen by a wild turkey.

Hearing their ambitions for the future, Iraj proclaims that there’s no hope for human survival and that “all of you will fail” before having them read a sentence on the blackboard: “We are lost forever in this world.” Then, he expels them all until Omid recovers his spectacles, declaring, “No more education. Everyone go stand in the closet!”

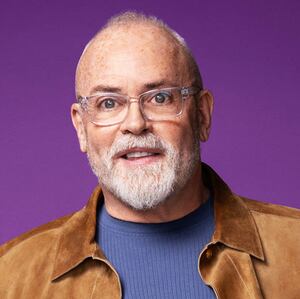

Showing at the 62nd New York Film Festival following its celebrated appearance at this year’s Cannes and Toronto fests, Universal Language is the drollest and oddest film of the year—and one of the funniest as well. Writer/director Matthew Rankin’s latest defies easy categorization and is all the better for it, segueing between absurdist registers with a deftness that allows it to both amuse and move. A fragmented tale about disparate individuals in search of themselves, community, and home—and, in its self-consciousness, about cinema’s ability to bring people together—it’s an off-kilter creation that feels like the wacko offspring of Aki Kaurismäki and Abbas Kiarostami’s cinemas.

A still from Universal Language

Courtesy of New York Film FestivalIn the aftermath of Iraj’s classroom tirade, Universal Language introduces us to its weird alterna-Winnipeg, where children line up to have three swings on the schoolyard’s lone swing, an adolescent photographer snaps pics of a classmate and his donkey, and Negin (Rojina Esmaeili) informs Omid that if she finds his glasses, she’ll return them to him. Every building in this metropolis—which is divided between Beige and Grey districts—is either concrete or brick, and they loom large over its inhabitants, often taking up most of the frame’s background. Marked by sharp angles and curved openings, this geometric architecture is as cold and drab as the city’s history, which includes “the Great Parallel Parking Incident of 1958” and a memorial to Louis Riel that’s located between a freeway and an exit ramp.

Navigating this milieu, Negin goes to a nearby floral shop where signs caution “Do not scream near the flowers!” and, for her good grades, she’s given a flower by the owner. In this store, she hands her gift to a stranger and convinces her sister Nazgol (Saba Vahedyousefi) to help her with “a matter of life and death.”

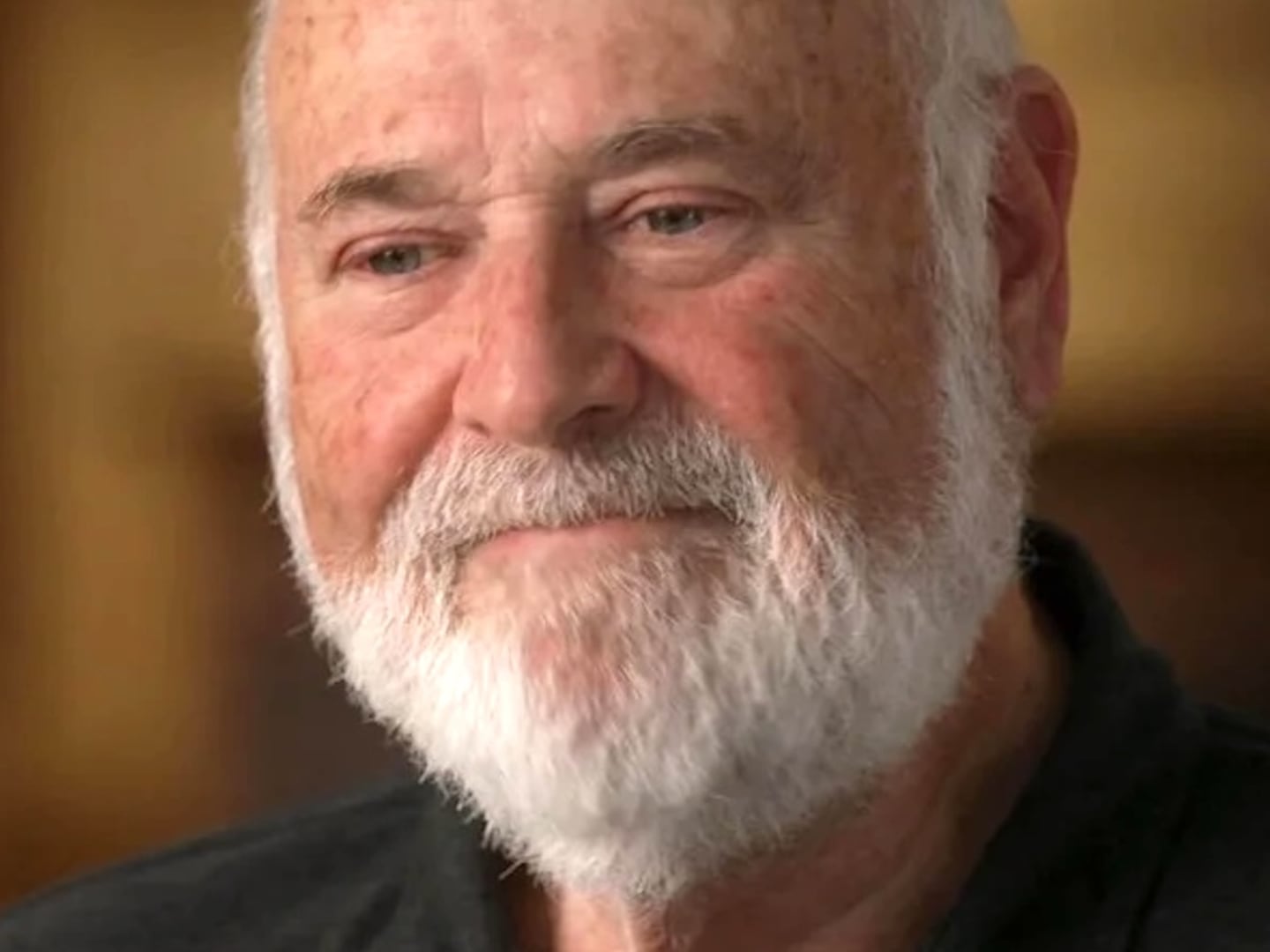

A still from Universal Language

Courtesy of New York Film FestivalThe issue in question is that Negin has found a 500 Riels note frozen in the ice and doesn’t know how to extricate it. As they discuss this dilemma, an adult stranger named Massoud (Pirouz Nemati) appears and recommends that they visit the nearby turkey store to get an axe. Negin doesn’t trust Massoud, believing he wants to steal the money, yet she and Nazgol follow his advice.

As they search for this business—asking directions from a man whose body is encased in a Christmas tree—Universal Language cuts to Montreal, where Matthew (Rankin) is quitting his government job. Meeting with a superior, he’s ordered to tell everyone that his experience in the Ministry was “preferably positive, but we can accept neutral.” Matthew agrees, admitting that “it was by far the most neutral experience of my life” while a man in a cubicle weeps loudly and the director cuts between his two characters’ perspectives to reveal that the room’s opposing walls are decorated in the exact same way.

After procuring sleeping pills from a pharmacy where fentanyl and ginkgo biloba are stacked side-by-side behind the counter in matching nondescript boxes, Matthew travels to Winnipeg and tries to find his mother. His phone call home, however, is answered by an unknown man who asks to meet him that evening at a local Tim Hortons, which sells Arabic tea as well as donuts and is frequented by women who silently knit at their tables.

At the same time, Massoud gives city tours to visitors who bitterly complain about its dullness, including a mall fountain that boasts no water, meaning “All wishes are canceled.” This and more bizarreness runs rampant throughout Universal Language. The film’s splintered narrative immerses viewers in its eccentric environment before it explains who its characters are and what they’re doing, and it employs transitional fades (courtesy of Xi Feng’s lyrical editing) to weave its various concerns into a pensive tapestry of loneliness, aimlessness, and longing for purpose and connection.

Rankin’s Matthew gradually emerges as the nominal protagonist, and his deadpan reactions and interactions are emblematic of the proceedings’ dry tone. Universal Language becomes less traditional as it meanders in multiple directions, casually laying out its plot strands and then intertwining them in unexpected ways until everyone winds up in the same place. Despite that climactic get-together, though, the writer/director’s tale is mysterious until the end, proposing that communion and happiness are possible and, also, that detachment from love and family results in a loss of self. Never italicizing its intentions, it suggests tantalizingly, all while providing a steady stream of nuttiness.

A still from Universal Language

Courtesy of New York Film FestivalDespite its multicultural set-up, Universal Language isn’t overtly political. Nonetheless, its borderless urban dreamscape—and its characters’ attempts to help themselves and each other—renders the film a witty plea for individual and social harmony.

Such notions course throughout its concise 89 minutes, even as Rankin devises one ridiculous sight and situation after another, whether it’s a turkey salesman in a pink cowboy hat, a man wearing a blue snowsuit and shiny reflective glasses who owns a head of magnificently long, curly blonde locks, Iraj admitting that his wife was fatally flattened in a steamrolling accident, a bus driver talking about a person who choked to death at a marshmallow-eating contest, or a “Forgotten Briefcase” on a bus stop bench that’s now a UNESCO World Heritage site and “a monument to absolute inter-human solidarity, even at its most basic and banal”—a description that additionally applies to this charmingly cockeyed comedic drama.