PARK CITY, Utah—No matter what progressives pronounce on T-shirts and social media, the rich can’t be eaten because they’re society’s true apex predators, eager to not only feast upon those beneath them but to afterwards arrogantly laugh and sneer at anyone who dares object. Such is the message of Veni Vidi Vici, Austrian directors Daniel Hoes and Julia Niemann’s satire about the super-wealthy, whose message is made during its opening minutes and then over and over again, to ever-diminishing results, for its remainder. Although handsomely mounted and occasionally chilling, it’s the cinematic equivalent of a one-note tweet.

Per the film’s Julius Caesar-inspired title, the Maynards have come, seen and conquered, and at the outset of Veni Vidi Vici—which premiered Jan. 18 at this year’s Sundance Film Festival—there’s nothing standing in the way of their continued rule. On a winding road, a bicyclist is suddenly shot by a distant sniper, and once the second bullet finishes him off, two men appear. The younger, Amon (Laurence Rupp), is dressed for cycling and takes the deceased’s bike. His bald accomplice, butler Alfred (Markus Schleinzer), stays behind to cover up the mess. All of this takes place in the bright midday sun, with other bikers and motorists passing by without giving the scene a single glance, and thus it’s no surprise that as he speeds down the hill, Amon lets out a triumphant “whoo hoo!” Despite the extremeness of his transgression, he’s untouchable.

Amon’s love for “the most dangerous game” is in tune with his business ethos. At present, he’s working to create a new complex in an unspoiled rural valley that will serve as Europe’s largest battery manufacturer. Pulling off this endeavor means screwing over his mentor Carl (Manfred Böll), but Amon doesn’t hesitate, since ruthless conquest and betrayal are par for life’s course. With profits to be earned, the local government minister is on board with this plan, regardless of the fact that she suspects, along with a colleague, that Amon is the serial killer terrorizing the region. A gamekeeper (Haymon Maria Buttinger) catches Amon in the homicidal act and yet is dismissed by local authorities, driving him to despair. Also anguished about Amon’s invincibility is Volker (Dominik Warta), a journalist whose attempts to convince his ex-wife Regina (Andrea Wenzl) to publish an exposé about the magnate goes nowhere, with Regina shrugging Volker off as a “flat-earther.”

Amon can get away with murder because he has money and, with it, power; he can shield himself from investigations by bribing others or hiring the best lawyers (should that situation ever become necessary), and moreover, people want to protect him so they can be in his good graces. This is, let’s say, not a particularly insightful point to make, and Veni Vidi Vici makes it far too mundanely. Hoes and Niemann stage their material with polished reserve, panning gracefully over the line of identical white Porsches that Amon uses to commit his crimes, and luxuriating in the opulence of his mansion, replete with an indoor lap pool and spacious grounds fit for prodigious birthday parties. However, while their restrained approach echoes the Maynards’ calm, confident sense of untouchability, it never generates any laughs or shocks. Where over-the-top outrageousness is needed, only manicured coolness exists.

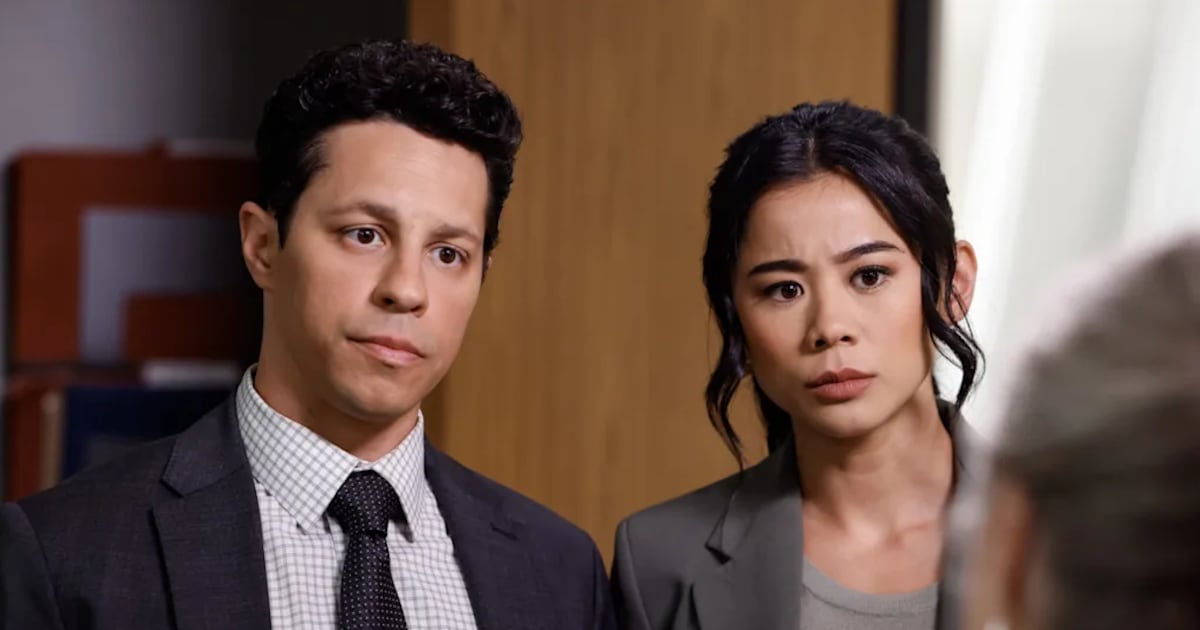

Amon is the central Teflon-Don villain of Veni Vidi Vici, but the film’s critique extends to the rest of his clan. Amon’s wife Viktoria (Ursina Lardi) is a public defender who represents the downtrodden—a legal position that makes her strategically useful as well as gives her family handy PR cover. Viktoria has long struggled to have children of her own and is now intent on using a surrogate to fulfill her dream, even though she’s already mother to three kids: 13-year-old Paula (Olivia Goschler), whose biological mom (Amon’s first wife) died in childbirth; and adopted adolescents Coco (Tamaki Uchida) and Bella (Kyra Kraus). That Coco and Bella are, respectively, Asian and Black is a reflection of the family’s ugly calculations; the unspoken implication is that Amon and Veronika selected them as a way to demonstrate their inclusive tolerance, thereby further insulating them from reproach. Yet like so much of the material, this detail is a pedestrian jab at these cretins, neither sharp nor funny.

Veni Vidi Vici’s secondary focus is Paula, who provides intermittent narration and subscribes to her father’s cutthroat code (“Everything created deserves to be destroyed”). Paula is frustrated that she isn’t allowed to shoot any of Amon’s numerous guns or to join him on his hunting trips with Alfred. Consequently, she amuses herself by playfully flirting with Carl’s son Sylvester (Laurenz Walter), whom she simultaneously looks down upon, and shoplifting at a local store with a friend who shares her conviction that if you don’t get caught, you deserve to have everything stolen. Paula is a chip off the old block, her entitlement resting on the foundational belief that she’s superior to her fellow men and women, and therefore permitted to do as she pleases until someone stops her. That they don’t proves that money buys influence; even after being scolded for this infraction and forced to apologize, her mate starts stealing again, and Veronika continues buying off the proprietor with shop renovations.

Hoes’ script argues that everyone is for sale and happy to be purchased, since fighting injustice and upholding laws (and morality) is far less beneficial—individually and collectively—than playing along and getting a piece of the pie. Veni Vidi Vici makes this familiar case from multiple angles but adds nothing new to it. Worse, it doesn’t care to articulate it with comically or terrifyingly wacko verve. The directors’ clean, pristine aesthetics, which include a soundtrack punctuated by opera and Ravel, capture the way in which these monsters cloak themselves in upper-crust refinement. What’s missing, alas, is the sort of genuinely wild exaggeration that might complicate, or at least energize, their censure. In spite of fine performances from Rupp and Goschler, the latter exuding a chipper friendliness that masks her inner vacancy, the film merely restates its thesis until the entire affair takes on an air of self-satisfaction that the Maynards would both recognize and endorse.