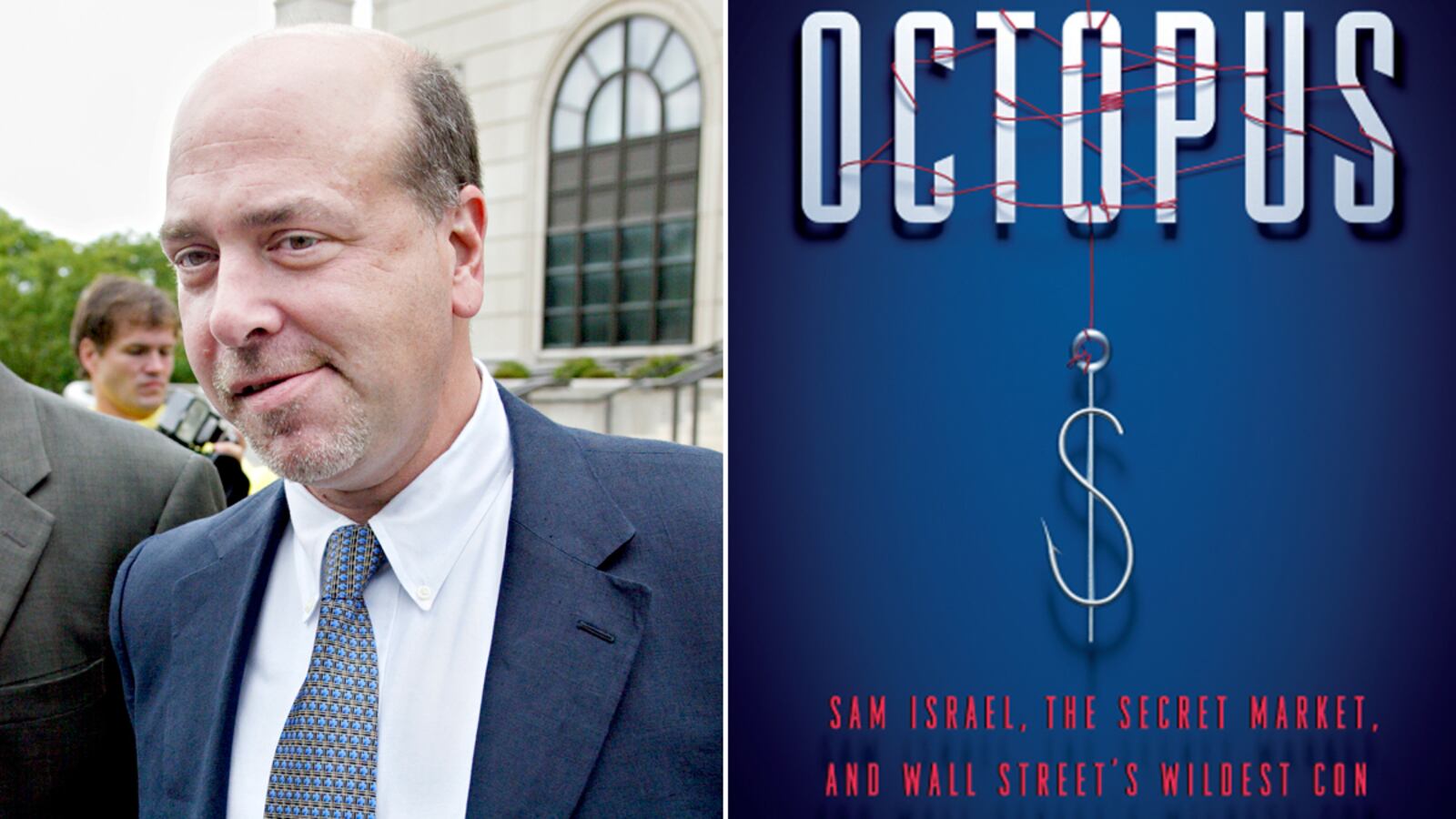

If you dig movies about cons, like Catch Me If You Can, The Sting, and The Spanish Prisoner you will blow through Octopus, Guy Lawson’s deftly and enthusiastically told tale of Sam Israel and the Bayou hedge fund fraud. If you think you know all about Ponzi schemes and have had enough, you don’t know the whole story. The Israel caper is the best real-life scam story since Ivar Kreuger convinced post-World War I America he had loaned money to Europe’s broken governments in exchange for monopoly rights to sell matches on the continent.

When Israel’s trading prowess failed to deliver the returns he had promised his investors, he lied about them and hoped to make up the losses later. While he faced few redemptions, there were no problems and for a while, he had an easy time raising capital. The hapless Wilpon family, which owns the New York Mets, even invested in Bayou to diversify the risks of its investments with Bernie Madoff. Israel’s scam was the familiar tale of a life that became a bigger lie that became a Ponzi scheme. It’s the scam that Israel fell for that is truly outrageous.

Desperate to make enough money to cover his promises, cover-over his lies, and salvage his reputation, a stressed-out Israel turned to a man named Robert Booth Nichols, who claimed to be a CIA “asset” and all-around international man of mystery. Lawson leaves it to us to decide whether Nichols had any role in covert operations. Handily for scam artists, Lawson points out, the CIA doesn’t confirm or deny claims of this sort. On the other hand, Lawson did find high-ranking military sources who knew the man, though they tended to regard him as a blowhard.

Nichols told Israel about a fantastic conspiracy of 13 families—including the Rothschilds, a conspiracy theory favorite—who control world finances through a secret “shadow market,” of bonds issued, at their direction, by central banks like the U.S. Federal Reserve. The scam works like this: bonds are issued and sold at a discount to certain selected financial institutions and secret wealthy traders. These bonds can then be sold at face value to people outside the loop. The guaranteed returns are split between the lucky trader and the cabal that runs the world, which uses its part of the proceeds to maintain global confusion and, to some extent, stability through charitable projects.

Fraud followers will recognize this as a “prime bank” scam, of the type usually used to ensnare Florida retirees. The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission even maintains a page devoted to prime bank frauds.

“‘I kept asking myself if it was all a con,” Israel told Lawson. “I was with Bob all the time. I saw everything that he saw. I knew how hard it was to keep up a fraud.”

Israel’s guilt and desperation had left him mentally vulnerable to the wildest of conspiratorial fantasies. But those weren’t the only causes of his belief. Israel comes from an influential New Orleans family, which had long participated in the global commodities trade. He grew up with connections in both finance and politics and knew well the advantages of private dealings with people of power. Also, Israel is a distant Rothschild, on his mother’s side.

When Israel tried to make a name for himself on Wall Street in the 1980s, he was trained by master traders of inside information who, in the days when trades were comparatively slower, used their non-public information of mutual fund buys and sells, as well as takeover information, to make quick profits. Israel was taught from the start that the investments were rigged to favor highly networked cheaters.

A final reason that he likely believed in the scam was that Nichols, now dead, seems to have believed his own story. Even while Nichols took Israel for $10 million of Bayou’s money—in exchange for a supposedly poison-rigged case of Federal Reserve bonds issued to fund China’s Chang Kei Shek attempt to resist Japan’s invasion—the con man seemed to believe that he needed the trader’s prowess to access the shadow bond market, where they could score real dough.

The one thing Nichols didn’t know was that Israel’s trading skills had been exaggerated.

In April 2008, after years of continually putting Bayou’s assets at risk of being stolen by a network of people that Nichols said could help them access the shadow market (at a few points, all of the money was almost absconded with), Israel was convicted of running Bayou as a Ponzi scheme and sentenced to 22 years in prison. Two months later he faked his suicide and attempted to run, only to give up when the police arrested his girlfriend, charging her with aiding his escapade.

In prison, Israel is still victim to the con. Though the Fed declared them clever frauds, he wants his Federal Reserve bonds back, he is convinced that he killed a man in Europe (long story, Lawson says it was staged), and he thinks he knows who really killed John F. Kennedy. Because what conspiracy is complete without that?