So this guy walks in and parks himself at the bar, a couple of stools down from me. He’s a type you see a lot of out here in Los Angeles—middle-aged Don Henley-looking gink, expensive jeans, expensive t-shirt, expensive ball cap, shades. The vague young bartender comes over and the guy speaks to him like you speak to the kid at the office who always gets everything just a little bit wrong but can’t really help it.

“Can I get a Tito’s and Soda, no fruit… and from now on, that’ll be a ‘club soda.’ I’ll be speaking in code.”

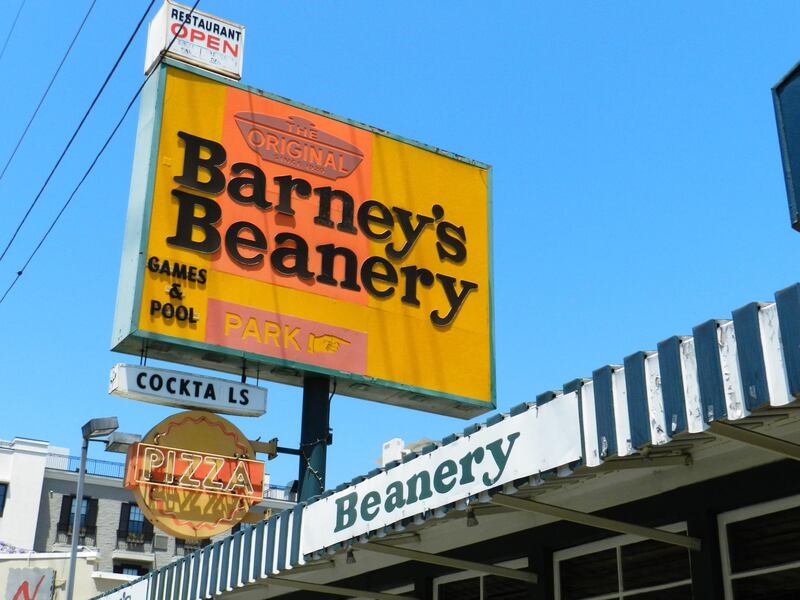

He pins the bartender with a flat stare until he gets a nod of comprehension and goes back to his phone. From where I’m sitting I can see 15 flat-screen TVs, tuned to three or four different games. There are 45 taps, almost all of them domestic, almost all of those IPA. The music playing is of the genre known to old guys like me as “sumshit.”

ADVERTISEMENT

I hate this bar.

But I’m glad it’s still there. Thirty-plus years ago, I was more or less a regular, and it was old then. It opened at its current spot in West Hollywood, California, in 1927, back before there was a West Hollywood. John “Barney” Anthony, a native Angeleno, was a Berkeley man, at a time when college grads were pretty thin on the ground, and he had been in the Navy during World War I. When he got out, he tried managing boxers and then came to his senses and opened a little hole-in–the-wall lunch counter in Berkeley, right by his alma mater. (In the Navy, he had been a cook.) That was in 1920. “Barney’s Beanery,” as he called it, was a hangout for the university’s undergrad literati—men only, please—until 1927, when a 9-year-old boy burned the building down for kicks.

Rather than rebuild in Berkeley, Anthony moved operations, such as they were, back home, buying a little bungalow at the spot where Santa Monica Boulevard bends southwest toward the beach. When Repeal came, he added a bar by the simple expedient of roofing over the breezeway between the bungalow and the building next door and knocking a hole in the wall.

Anthony kept the old name, but this time, he let women in. Among them were the likes of Clara Bow, Veronica Lake, Jane Wyman, and Marilyn Monroe. Movie stars. Plenty of their male counterparts came in, too, from Clark Gable to Vincent Price to professional Irishman Barry Fitzgerald, who used to spend his afternoons there.

Despite the fame of his clientele, who eventually stretched to the likes of Herbert Hoover and Earl Warren, Barney kept his place the same cheap hash-house it had always been. The kitchen was famous for its French onion soup and its chili con carne (billed as “L.A.’s second best,” perhaps as a poke at Chasen’s, the no-longer-cheap-at-all hash-house that was the reigning celeb joint in town and was famous for its chili). The bar was famous for—well, it poured a lot of beer.

Indeed, that refusal to get fancy is why Anthony had the famous clientele, a great many more movie stars having begun life among the hash-house classes than in the pheasant-under-glass ones. Of course, they wouldn’t have come if it was an ordinary, working-man’s joint. But Anthony was smart enough to butter the place with a thick layer of irony, so that it was both a real hash-house and a “hash-house.” The menu was labeled “Poison Chart,” there were ridiculous signs all over the place, the hours were from 5 PM to 5 AM, the décor was mostly license plates, old and new, and if the celebrities had to “wait in line with truck drivers and bookies” (as one journalist noted), once they got in there were always plenty of other movie folk in there to make them feel at home, even if some of them were only directors or screenwriters or whatnot. And if they were between pictures and feeling the pinch, Barney would take an I.O.U. To be sure, he’d also take their license plates as security, but they could worry about that tomorrow.

By the late 1950s, though, Old Hollywood was pretty much through. Many of its favorite watering holes began to fade, growing old and staid with their clientele. But not Barney’s: the next decade saw it reborn as a Bohemian artist’s hangout, with Ed Kienholz and Dennis Hopper and all the various weirdos that made up the Los Angeles art scene eating the same chili and drinking the same beer. Kienholz even immortalized it with “The Beanery,” a three-quarters life-sized installation representing the Beanery’s bar and its patrons, only with everyone’s but Barney’s face replaced by clocks.

As the decade wore on, the artists were joined by the musicians and the freaks. The Doors were regulars at the bar. R. Crumb labeled a building “Barney’s Beanery” on the cover of Big Brother and the Holding Company’s Cheap Thrills, even though it looked nothing like Barney’s.

When Barney Anthony died in 1968, Irwin Held took over the bar, with the avowed aim of keeping things exactly the same as Anthony left them. Unfortunately, that included the ironically spelled “Fagots Stay Out” sign that Anthony put up some time in the late 1940s or early 1950s, possibly, as it has been suggested, to appease the vice squad, who thought the place wasn’t unfriendly enough to Hollywood’s much-persecuted, heavily closeted gay community. The sign was apparently never backed up by policy, but when, in the 1960s, people began to rightly complain about it as a matter of principle, Anthony dug his heels in, as did Held after him. It was part of the décor and it was staying. The louder the complaints, the more stubborn Held got (in fact, there were times in the 1970s when the sign was down; it seems like he put it back up when criticized). When West Hollywood was incorporated in 1984, it encompassed a large, thriving and open gay community, and an anti-discrimination ordinance was practically the first thing on the new city government’s agenda. The sign came down for good.

I moved to West Hollywood in 1985, in time to catch the tail end of the artists’ and rockers’ Barney’s. I was playing bass in a psychedelic-punk band at the time, so it was my kind of place. The restaurant part had been expanded and the menu stretched to hundreds of items, most of them endless variations on plain old bar grub. But the bar—besides stocking 175 beers, almost all in bottles and most imported—was pretty much as it had been in the 1960s and 1970s. Jukebox, beer, whiskey, lots of rock and roll types. It wasn’t a metal bar like the Rainbow or a punk one like—well, punks didn’t have their own bars; they just drank at all the Bukowski bars; the rundown old-man joints with which Hollywood was so liberally studded at the time. The rock and rollers at Barney’s were a little older, holdover ’70s longhairs and such. There were a lot of roadies. It was a sporty crowd—I saw one bartender get a hundred-dollar tip on a beer for the wisecracking way she delivered it.

My friends and I didn’t know much about the bar’s history, or care. I knew it had a history from the “crap on the walls” (the proper term of art in the bar-reviewing business) and the graffiti that was everywhere, but that wasn’t why I came. It had good beer, available in pitchers, a good jukebox, and the bartenders were quick and salty. Conversation at the bar was inclusive, wide-ranging, anecdotal and amusing. There was pool and pinball. If there was a TV in there I don’t remember it.

Held sold the place in 1999. The new owners kept things as they were for a while, but then they started opening branches around L.A., including in the airport (never a good sign). I don’t know when the TVs showed up, but once you’ve got the whole place covered with them you’re never going to get the kind of patrons who prefer to entertain themselves; the kind who turn a bar into a free-floating party where everyone who can be cool is invited.

When I popped in the other day and found Mr. Club Soda (in the old days, if he had asked one of the tough girls or gruff guys who worked the bar at Barney’s for “club soda” wink, wink, they would have given him club soda) and all the TVs, there was a little knot of old guys in the corner who looked like they might possibly be up for a little liveliness should any break out, but the other patrons were gawping at the TVs or their phones and conviviality was conspicuous by its absence.

But Barney’s is still an old, old bar, and under the screens it’s pretty much intact. There’s something intangible that old bars have, an atmosphere that leaches out of the beams and joists and rolls down the walls like fog down a cliff. Given the slightest encouragement, the spirit of community thrives in it like moss in fog. If you pull those beams apart, replace the joists, replaster the walls, grind the cigarette burns out of the bar, dust and scrub and paint and polyurethane, that atmosphere disappears.

Right now, it’s perfectly possible that the old, louche, free-swinging Barney’s could come back. Take the TVs down, rewire the old jukebox, switch out some of the IPAs for Pilsner Urquell and Trappist ale and such and—most important of all—find a couple of salty bartenders with a point of view, or if they’re already there, empower them to make some changes. Next thing you know it’s back to being a real “bar bar,” to use the term coined by the great Jim Atkinson, dean of American bar taxonomists, for regular, real-people bars; for the “institutions that exist as a sanctuary for those of us who just didn’t want to be anywhere in particular at the moment.”

One thing, though: There’s a plan being floated to dismantle Barney’s, put the parts in storage, build a multistory hotel on the site, and then remantle—is that a word? If not, let’s allow it so we can get to the bar—it in a space on the ground floor. Of course, that won’t work: Once those nails come out, the fog goes with them. And when that’s gone, you might as well be drinking at the airport.