No matter how adventurous the eater, there is always something he or she just can’t tolerate. While I’m not quite Andrew Zimmern, there are only a couple of things that I don’t ever want to eat and they’re pretty pedestrian: zucchini and chopped liver.

Often enough, I’ve found that culinary opposition is based on a past mistake or on ungrounded suspicion. Many people I’ve met who proclaim that they don’t like sushi usually have never actually tried it.

The good news is that these opinions can sometimes be changed. Over the years, I’ve had a number of people tell me that they don’t like gin. I typically ask if they’d be willing to try a drink. “You don’t have to finish it if you don’t like it, just give it a shot,” I tell them. Then I fix them a cocktail with three-parts gin and one-part Lillet Blanc, a dash of orange bitters, stirred for a full thirty count and whammo, they’re suddenly into gin.

Okra, however, is a much harder sell.

For many people, okra is at the top of the list of things they do not like to eat. They will not be convinced of its virtues no matter how it’s cooked.

You can score a few converts by deep frying it or slicing it in half and roasting it or grilling it—it’s the slime that people don’t like, and the slime, fortunately, cooks off.

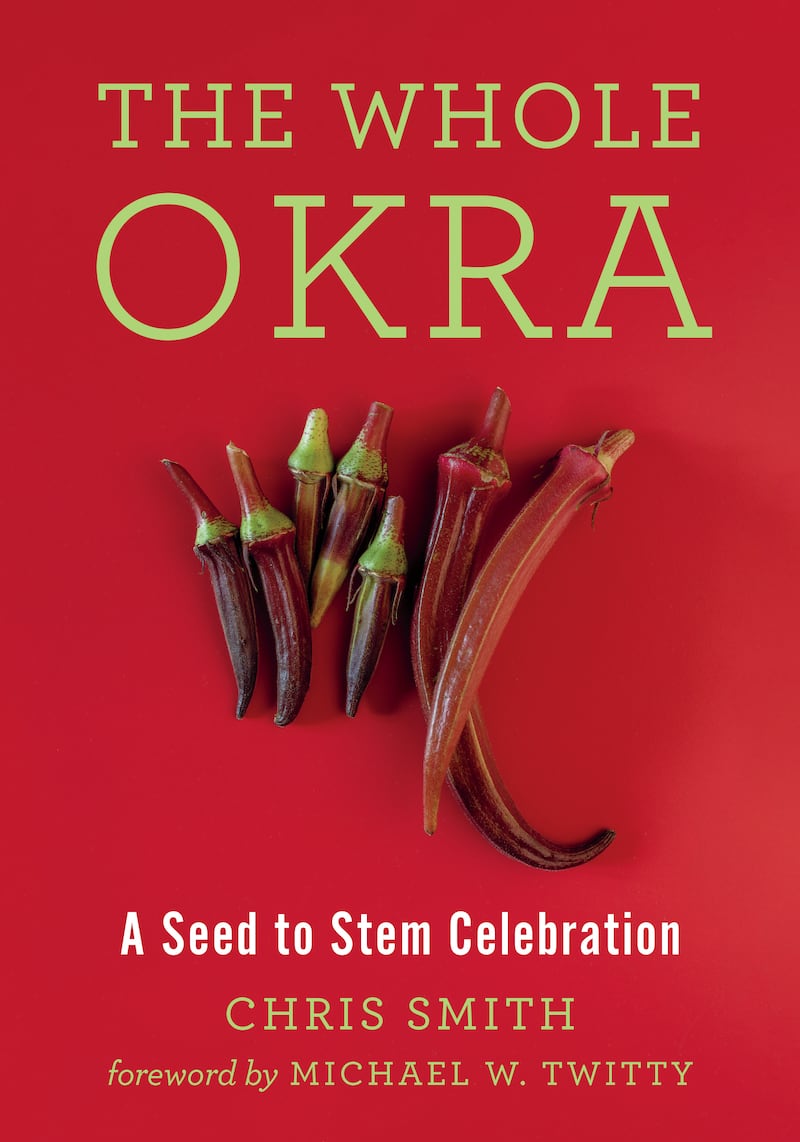

I personally love okra. But my love, however, does not hold a candle to the passion that beats in the breast of Chris Smith, who is the author of The Whole Okra. If there’s any way to cover okra after this exhaustive new book, I can’t imagine it. This is definitive. There seems to be no angle of the plant that Smith has left unexamined, no avenue unexplored.

I don’t feel the need to make okra ornaments for the holidays or to make cordage from okra fibers, but I am impressed by the fact that it can be done, and that Smith knows how to do it. I certainly look forward to okra flower infused vodka—it actually turns red, and Smith describes the flavors as robust and vegetal.

The flavors throughout the book are the star, and most of the recipes come from food writers and chefs. You’ll find Sandor Katz’s fermented okra, Sean Brock’s pickled okra, Michael Twitty’s okra soup, Virginia Willis’s round steak and okra gumbo, and Vivian Howard’s okra fries.

They’re all great. I flipped over B.J. Dennis’ recipe for Limpin’ Susan. “Limpin’ Susan has often been called the wife (or sometimes cousin) of Hoppin’ John, the more famous dish of peas and rice traditionally made on New Year’s Day,” Smith writes in the headnote. “There are many variations of Limpin’ Susan, but they always include rice, shrimp, and okra, and often bacon.” It’s like a sort of Gullah Geechee fried rice, thickened and bound together by the okra, and it just screams summer to me. The leftovers also make for an amazing omelet filling.

Throughout this history/cookbook/gardening guide, Smith remains charming. He even introduces his own recipe for okra seed pancakes, which he’s been feeding to his family for three or four years. Oddly, he doesn’t actually indicate that they’re good. The closest thing to an endorsement is that he says “someone would have told me if they were terrible!”

Make no mistake, however, his knowledge is serious stuff. He drops science throughout, and it’s wonderful to pick up little facts and insights that move the discussion outside of the world of okra.

And then, towards the end of the book, is the icing on this okra cake. Smith actually went to the trouble of planting 60 varieties of okra, from all over the world and tasting them with a panel of judges to find out which is the best. His results are cleverly tallied in a handy table that includes notes on the origin of the variety, the shape, the color and the spininess of the pods, and notes on how it grew. This is gardening gold. I know what I’m planting next!

But, of course, he must know that there are many who will turn up their noses at the mere mention of an entire book about okra. I wish they’d give the veggie a shot, but if they won’t, that means there is more for us! Maybe they’ll eat my zucchini or chopped liver...