In February, a 95-year-old man was deported to Germany, a year after he was found to have served as a guard at Meppen, a Nazi concentration sub-camp of Neuengamme. It wasn’t one of the worst camps—it had no modern gas chambers, but instead relied on the old-school expedient of working the prisoners to death. An assemblage of Danes, Dutch, French, Italians, Jews, Latvians, Poles, and Russians were forced by the guards to dig anti-tank fortifications during the winter of 1945, “to the point of exhaustion and death.”

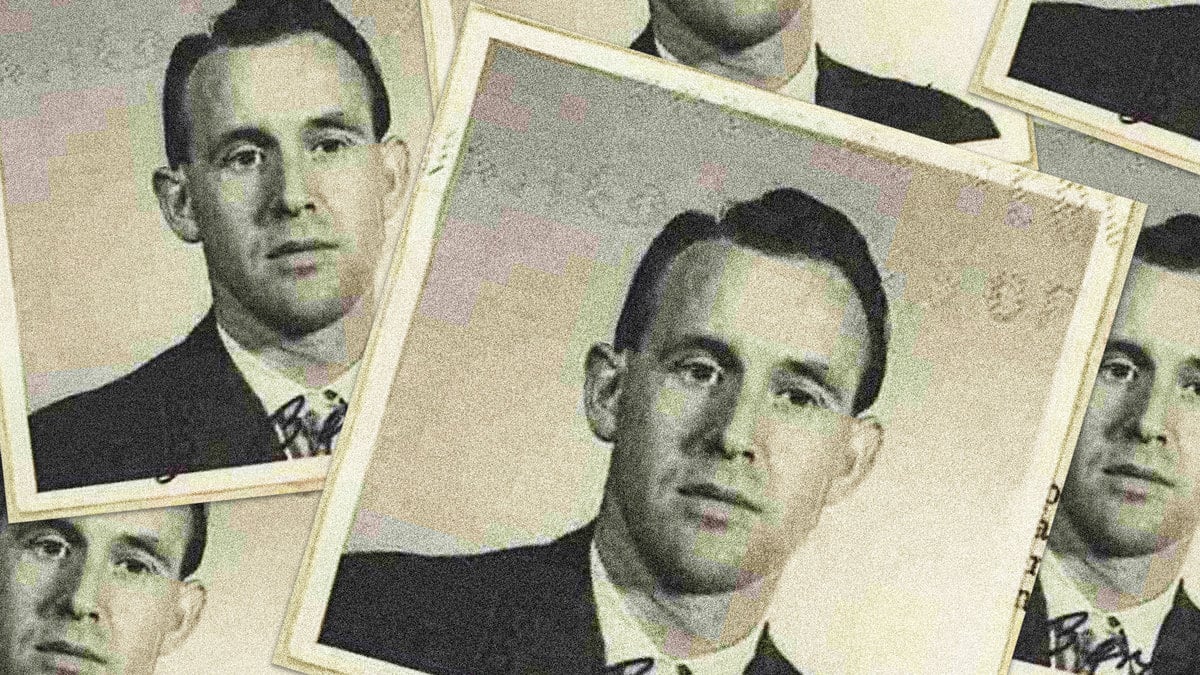

This particular guard, Friedrich Karl Berger, who had lived in comfort and safety in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, since 1959, enjoying, presumably, all the benefits of life in the U.S. for law-abiding citizens who keep their heads down, claimed he was 1.) just following orders, 2.) they’d made him do it, 3.) he hadn’t been there long, and 4.) he couldn’t be tied to any particular murder.

That defense, however, which had worked to the advantage of so many death-camp low lives in the past, proved outdated, and had since John Demjanjuk, a death camp guard who’d been living his own version of the American good life as an auto worker near Cleveland, was convicted in 2011 on 28,000 counts of accessory to murder. This legal construct gave prosecutors a way in, since it had proved nearly impossible to pin specific deaths on the surviving perpetrators, particularly as years went by.

And it came just in time. The last of these war criminals are now in their nineties, some older. One former guard under indictment in Germany is 100. Apologists for these ancient criminals are suggesting that bygones be bygones. That we the people let them live out their lives in whatever peace they have conjured for themselves. That we “leave justice to God.”

This argument might better wash if there were evidence of some moral atonement on the part of the perps. But they, for the most part, seem to have walked away from the death camps, whistling a merry tune. Some were helped to South America via the Ratline, with our CIA paving the way. Josef Mengele, the sadist who found his spiritual home at Auschwitz and whose only regret was that the killing didn’t reach its ultimate conclusion, lived pleasantly amidst friends and supporters in São Paulo till he drowned swimming at his leisure on a beautiful beach. That list goes on, and on, not excluding the princes of commerce, most of whom profited from slave labor. Bayer, Siemens, I.G. Farben, Krupp, Mercedes, and Volkswagen built their factories right next to the death camps and signed contracts with the SS, who would provide a specified supply of guards, dogs and whips, along with steady replacements for prisoners who would, it was understood, be worked to death. None of those responsible paid any significant price.

In light of this, these last old Nazis being dragged in to face the music at this point look like very small fry, as indeed they were and are. On the other hand, as Raul Hilberg pointed out in Claud Lanzmann’s film Shoah and elsewhere, it was these cogs on whom the whole death machine depended. Without the guards at the camps, or the schedulers of the trains full of prisoners, running with storied efficiency day and night, or the wholesalers of the barely used baby clothes flooding from Auschwitz into Berlin, none of it would have worked, or not nearly so seamlessly. Even a guard who didn’t personally sic his dog on a faltering inmate or turn a beautiful young girl over to Ilse Koch to make her skin into gloves, was, if you stand back a bit, guilty.

And where there’s guilt, there’s also a need for justice. Without it, one is left with resignation, fine for a Buddhist monk in a rhododendron forest, but not quite the thing for a judge and jury in contemporary America—not to mention a general public, who have by now read Anne Frank and Night. Who had to watch last month as home-grown Nazis sporting “Camp Auschwitz” hoodies beat our own police officers to death.

As we seek justice in Washington for these contemporary crazed haters, who, by the way, we can easily see standing shoulder to shoulder with the last of these indicted Nazis, whip or club or fire extinguisher in hand, we are reminded viscerally of why it matters so much. As Hannah Arendt wrote in Eichmann in Jerusalem, what we as a society are saying is that “Something happened… to which we cannot reconcile ourselves.”

Nor are we, as Americans whose fathers and grandfather fought and died to stop the Nazis, willing yet to reconcile ourselves to what happened to men, women, and children at their hands, not while there is still some measure of punishment to be meted out. It’s true that these last convicts are old, but “Justice has no expiration date,” as Christoph Heubner, vice-president of the International Auschwitz Committee put it.

Berger protested his deportation to a judge. “After 75 years, this is ridiculous—I cannot believe it. You’re forcing me out of my home.”

Welcome to the Holocaust, Mr. Berger.

Victoria Shorr is the author of the novel The Plum Trees, a story of loss and survival during the Holocaust.