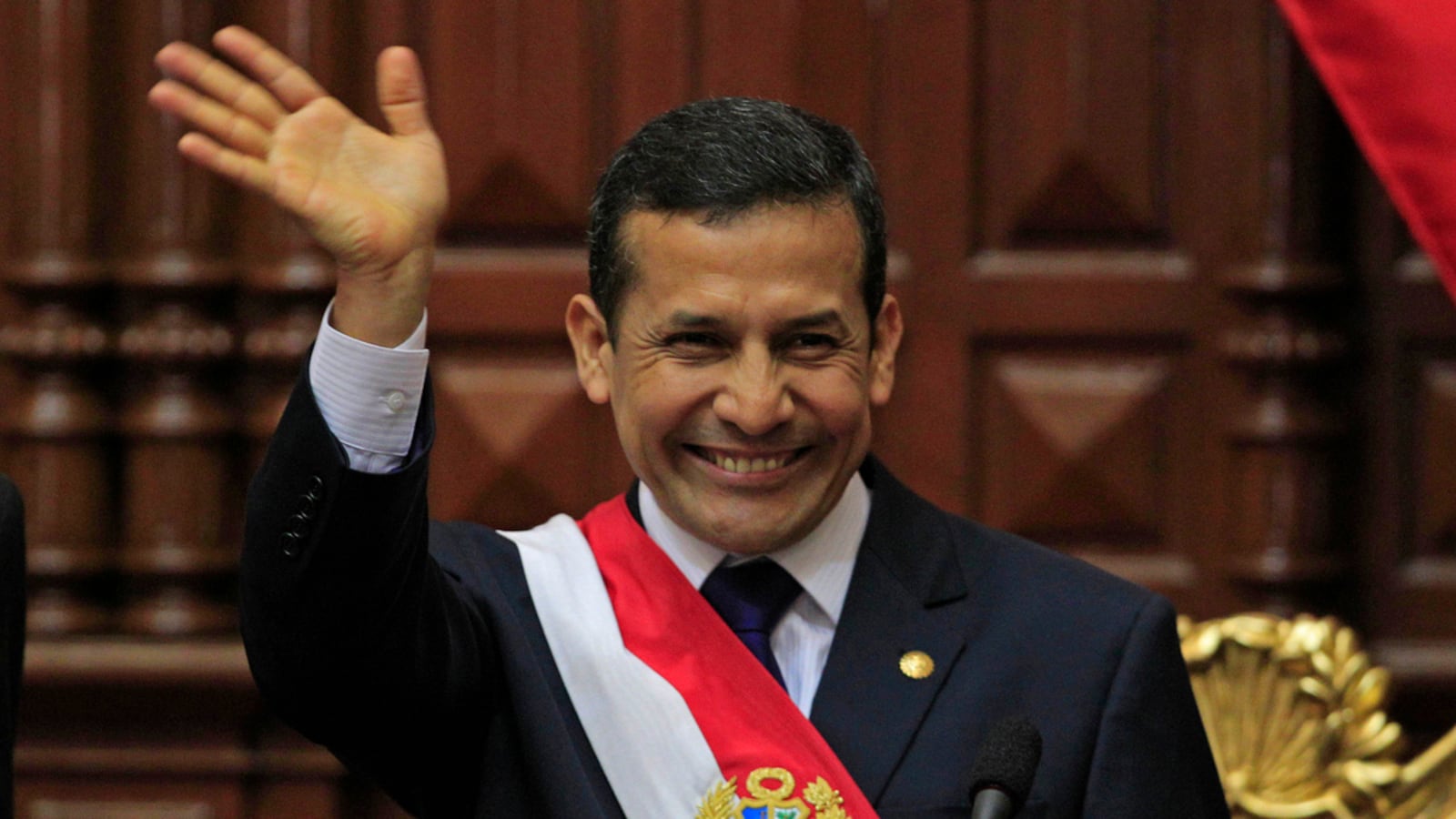

When Peru’s new president, Ollanta Humala, was sworn in last week, there was a little something for everyone. For international and local investors spooked by his incendiary political past, he rolled out a cabinet brimming with business executives and notables from the Peruvian establishment. In a nod to neglected minorities, he named Susana Baca, a famed singer who is black, to tend the culture ministry. And to “Ollantistas”, his longtime comrades on the left, he served up “Peru for all,” a grab bag of benefits including a 25 percent hike in the minimum wage over two years, universal pensions, and a new ministry of development and social inclusion.

That is the good news from Lima, where the onetime military man, best known for his fevered nationalist rhetoric and a failed coup d´état in 2000, is trying to repackage himself as a statesman and conciliator.

That is also the troubling news. Humala seems ill-suited for the high wire. The 49-year-old retired lieutenant colonel rose to national politics from the hard left, promising to bring foreign investors to heel, rewrite the constitution and return the national economy to state care. Having failed to gain power by bayonet, he befriended Hugo Chávez, the fiery president of Venezuela and herald of so-called “21st century socialism”, and vowed nothing less than a revolution by ballot box—the bourgeoisie be damned.

This rising nation of 30 million, riding a decade-long run of prosperity, had other ideas, and split its vote in a crowded field, sending the 2011 race to a runoff in June. Humala saw the graffiti on the wall and dialed back, climbing into a suit and tie and trading in the balled fist for an ecumenical abrazo to Peruvians mighty and meek. He even hired professional spin men, flying in ringers from Brazil’s Workers’ Party, the party of ultrapopular former president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, who branded him the Lula of the Andes.

But there’s quite a distance between the stump and the presidential palace, and now Humala has the unenviable task of keeping his balance in this patch of the hemisphere where even the most successful and celebrated leaders can quickly fall from grace. Already doubts have arisen.

Consider Humala’s promise on the inaugural dais to abide by the national constitution—not the current one, but the prior version, drafted in 1979. The reference was a swipe at the 1993 charter written during the tenure of Alberto Fujimori, the divisive dictator who closed congress and ruled with an iron hand.

Humala has a point. Though drafted by legislators and approved by a national referendum, the current constitution was heavily influenced by Fujimori. (His opponents boycotted the election of the constituent assembly that wrote the charter). But it also sanctioned economic liberties—privatization and rolling back state interference in the market—that untethered the economy and transformed Peru from a chronically dysfunctional nation into a model for Latin America.

The result has been the most spectacular jag of growth in the region. Surfing the commodities boom, Peru’s economy has expanded for the last 12 consecutive years, with low inflation and nearly $47 billion in international reserves. With jobs in mining and construction on the rise and better social spending, the number of Peruvians living in poverty has dropped from nearly half to 31 percent, in a decade. And another $42 billion in foreign investments are reckoned to be in the works in mining alone.

Humala has every reason to tout the “other Peru”, the nearly 10 million working poor and indigent who have not caught the prosperity wave. But he also knows how to count. Elected by a thin majority in a bitterly divided campaign, his party, Gana Peru, controls only 47 of 130 seats in the new congress. Tellingly, Humala has turned away from Chávez, his putative godfather during his failed 2006 presidential run. His first international visit as president-elect was to Brazil, and he even made a surprise call on Barack Obama in mid-July.

His cabinet includes five business executives and seven ministers of former governments, not least in the key economic posts. He has retained Julio Velarde, a button-down administrator, in the Central Bank, and soothed market jitters by naming as finance minister economist Miguel Castilla, who has diplomas from Harvard and Johns Hopkins. His prime minister is prominent businessman and human rights advocate, Salomon Lerner, and his closest political ally is former president Alejandro Toledo, a stolid moderate.

Call it a political hedge. Humala takes over a country that is growing fast but also eager for changes and traditionally merciless with leaders who fail to deliver them. Just ask Alan Garcia, the outgoing president who presided over the most sustained run of economic growth in the last half-century, with a record drop in the poverty rate, and who left office by the back door, his popularity in tatters. Garcia did not even show up to pass the sash to Humala.