Last January, I sat in a packed audience at the Sundance Film Festival screening of On the Record, a documentary by directors Amy Ziering and Kirby Dick on rape allegations going back four decades against hip-hop impresario Russell Simmons. To date, upwards of a dozen women have accused him of committing sexual assault. Ziering and Dick had invited me to participate in a panel discussion around the movie, the following day. In the weeks leading up to its public debut, the film’s notoriety had been dramatically ratcheted up by online protestations and accusations of racial treachery from Simmons himself, musician 50 Cent, and other predominantly black voices against executive producer Oprah Winfrey and the white filmmakers. Winfrey pulled her support and affiliation with On the Record just before Sundance began citing creative differences, and in the process taking an Apple TV+ distribution deal with her.

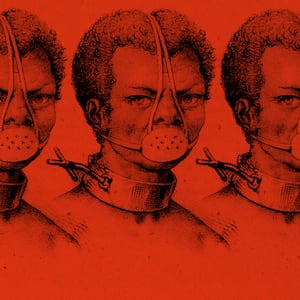

That premiere night at Sundance watching On the Record, I felt helplessly, profoundly ashamed. Overwhelmingly surrounded by hundreds of white women, I couldn’t help feeling defensive and hurt that there weren’t more black men in the film supporting the black women baring their trauma—and weren’t more black people in the audience with me in general. As several women in the film noted, they tried to share their stories with the black press and other filmmakers, but none seemed to express serious interest. A core part of me needed a chorus of black voices to bear witness and in doing so, acknowledge that black Americans—black men—have largely erased the pain of black women from our community narrative, especially when we are the direct cause of it. Now is the time for us to share the journeys of survivorship and for black men, as well all Americans, to listen. From slavery to the present, black women’s bodies have been systemically violated and exploited by white Americans, and kept out of the spotlight by black men.

Across generations, there has been an understanding within the black community that it’s better to keep silent about that particular form of lateral oppression rather than surrender more black men to a system of mass incarceration in service to white supremacy. “Now is not the time” is the well-worn refrain whenever attempts are made to have a candid, open conversation in public forums, or supposed “safe spaces.” It offers no solace, or salve. In cold, hard terms black women’s survival demands that as a community we do. As a young West African activist told me years ago, “when you rape a woman, you rape an entire village,” and the generational legacy of black men abusing and raping black men has left us with few if any communities untouched by profound rape-related trauma.

Though they comprise only eight percent of the country’s population, black women comprise 20% of domestic violence-related injuries, while homicide remains one of the top five causes of their deaths. Only one out of every 15 black women who are assaulted ever officially report it. Black women have among the highest rates of all demographic groupings for breast cancer, maternal mortality, suicide, homicide, increased incarceration, and harmful drug use, but few if any notably gender-inclusive campaigns addressing these issues have ever been launched within the black community. Their health and survival cannot be their struggle to bear alone.

To be sure, there are scores of black men advocating with and for black women across this country, such as Quentin Walcott at Connect NYC, Ulester Douglas with Men Stopping Violence, or Brian O’Conner from Futures Without Violence. They are not black unicorns. In so many ways, their work of deconstructing a black masculinity modeled on white male supremacy is imperative.

As journalist and hip-hop feminist Joan Morgan observed during a panel on which I participated the day after On the Record’s Sundance premiere, “We have never had a definitive talk about rape, the transatlantic slave trade, and what happened to black women when they came to America. We never talk about the sexual violence in slavery, the rape of black women by white men, and black men,” she continued. “So, black men have been able to develop a narrative that says ‘whenever someone accuses me of rape they’re lying because white women did, and we were lynched because of it.’ We’re talking about black men...whose model of success is the white boys who are powerful. That is the model, and until we come up with a different definition of what liberation [and black manhood] looks like in our community...we are fucked.”

Mainstream (white) Americans may have the luxury of being historically uninformed commentators, rhetorical “bomb-throwers,” or disinterested bystanders to the inevitable online dragging, or shade that’s thrown when questions are raised about a black man (typically a celebrity) for their alleged sexual abuse(s), but for black Americans, the rallying cry “Black Lives Matter” must finally be made to realistically and meaningfully include women. True racial equity is impossible without gender equality and safety. A 280-character tweet or a video testimonial on Instagram is not enough for the necessary “real talk” which needs to happen, and frankly an editorial in a publication such as this one might not be as well. These conversations must happen where people actually live—around the kitchen table, in afterschool programs, in the car on the way to church and then during the sermons, on basketball courts, street corners, bars, barber shops and hair salons, and one-on-one. For all of us, now is the time to find safety and speak the horrible truths of what we do to each other, and the consequences. It’s about airing the dirty laundry, the business we won’t put out in the street, and seeing violence against black women as a personal matter.