Last week, a gardener at the Ricci Oddi modern art gallery in Piacenza, Italy, was tackling some overgrown ivy when he discovered a hidden metal panel in the building’s exterior wall.

He opened it and found something very unexpected inside—a black bag containing a painting believed to be Gustav Klimt’s “Portrait of a Lady” that had been stolen from the same gallery 23 years earlier.

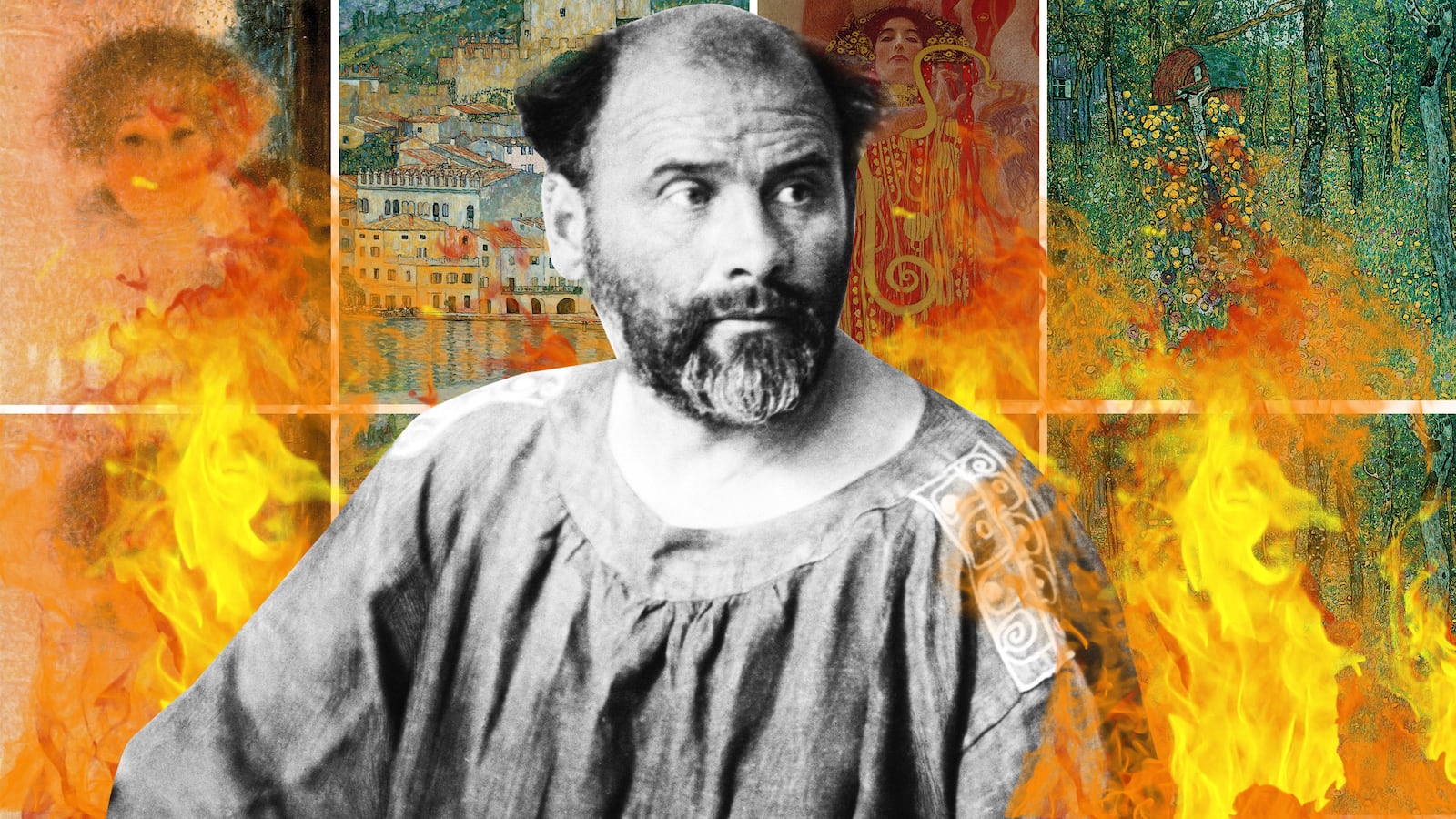

Once this find is authenticated—if it is indeed the painting that was removed from the gallery via skylight on Feb. 18, 1997—it will be a big win for Klimt’s oeuvre. While the legacy of the Austrian modernist painter has only grown since his death in 1918 (today, his “Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I” has achieved nearly universal recognition), his body of work took a significant hit during World War II.

Klimt counted many of early-19th-century Vienna’s most prominent Jewish families among his greatest patrons. The Bloch-Bauers, the Wittgensteins, and the Lederers all supported the artist through commissions and acquisitions. But when the Nazis invaded Austria in 1938, German officers began confiscating their collections.

Many of the stolen works have been mired in restitution battles in the decades following WWII, but a large number of others didn’t survive the conflict. Among them was the Lederers’ collection of Klimts—“the most important single collection of the artist’s work,” as Anne-Marie O’Connor writes in The Lady in Gold—which burned in the tragic fire at Schloss Immendorf in the waning days of the war.

August Lederer was a wealthy industrialist in turn-of-the-century Vienna, but it was his wife Serena, a member of the famous Pulitzer family, who first made the connection to Klimt.

The socialite was an art student of Klimt’s for several years, and supported him behind the scenes doing things like loaning one of her ethereal silk gowns to Mizzi Zimmerman, a model for the 1899 painting “Schubert at the Piano”. (The Lederers would come to own the Schubert, which was among the victims of the fire; soon after the modeling session, the young Mizzi would bear one of Klimt’s rumored 14 illegitimate children.)

“Vienna was not very well disposed towards modern art, and the Lederers were also traditional in their collecting habits. They lived at 9 Bartensteingasse, near the new town hall, in Vienna’s smartest residential area, and their apartment was full of remarkable art treasures,” Christian M. Nebehay writes in Gustav Klimt: From Drawing to Painting.

But something happened around 1899 to change those artistic preferences. At the turn of the century, Klimt was becoming a champion of Modernism in Vienna, and he served as the first chairman of the Secession movement started by pro-Modernist artists who broke off from the country’s traditional art establishment in 1897.

It was in 1899 that Klimt painted Serena for the first time in a portrait that is often described as “Whistler-like,” referring to the American painter James Whistler. With this commission, the Lederers began to assemble what would become an impressive collection of Klimts.

Nebehay’s father owned a gallery in Vienna in the early 1900s, which is where the Lederers purchased the majority of the Klimt drawings they would come to own. The writer tells a story of the day in 1919 when his father was preparing to open an exhibition of Klimt’s sketches and Serena “swept” into the gallery.

“She took a short look round and then said: ‘What does the whole thing cost, Herr Nebehay?’ My father thought he had not heard aright, but she continued: ‘Did I not make myself clear? I said the whole thing and I meant it. So what does it cost?’ My father hastily counted up the prices from his list and named her a sum. ‘Done!’ came the answer, ‘send the lot to me at Bartensteingasse. Good morning!’ and out she swept again, leaving my father speechless.”

But one of their greatest painting acquisitions came much earlier than that in 1905 after August Lederer helped Klimt out of a sticky bind.

In 1894, Klimt had received a joint commission with the artist Franz Matsch to create paintings for the gilded Great Hall at the new University of Vienna. Klimt was responsible for three of the large corner paintings that were to depict the faculties of Philosophy, Medicine, and Jurisprudence. But when professors at the university got wind of what the modern artist was working on, a scandal immediately erupted.

No color photographs of the three paintings were ever taken, and they all tragically perished at Schloss Immendorf. All we are left with of these monumental works are some black-and-white images, preparatory sketches, and the angry words traded between the two camps in the vitriolic debate that raged over the merits of Klimt’s work.

The anti-Klimt side included the majority of the college’s faculty, who wrote a petition in 1900 requesting that “His Excellency the Minister of Education” stop the planned installation of Philosophy in the great hall. The art professor was conspicuously absent from this group.

In a lecture entitled “What Is Ugly?” he stood up for Klimt saying, “Seldom has an artist paid greater homage to science. And now the doors of its temple are to be closed on this great-hearted artist. So it goes: enthusiasm is infectious, but so is malevolence.”

And with these scholarly barbs thrown, the flood gates opened and the rest of Austria’s literary establishment weighed in.

If they thought “Philosophy” was bad, “Medicine” and “Jurisprudence” were worse. The latter painting presented viewers with “this emaciated, naked old man with bowed head and bent back…there he stands, from his profile utterly lost, irretrievably condemned…On the canvas he was still a shadow, tormented by three wraiths,” as journalist Ludwig Hevesi described.

“Medicine” was even more shocking. Klimt had the audacity to paint both a naked woman and a pregnant woman on the canvas for all to see. As one anonymous contributor to the public flogging wrote in 1901, “The figures in them might perhaps be suitable for a museum of anatomy, but certainly not for public display in the University… the coarseness of conception and lack of aesthetics being deeply offensive to the general public.”

The scandal finally came to a close in 1904 when Klimt, who later told a friend that he didn’t mind the public vitriol but found the disapproval from the employers who had given him the commission to be “absolutely humiliating,” withdrew from the project, returning the commission money with the help of Lederer in exchange for retaining ownership of the three paintings, which were returned to him the next year.

Lederer quickly bought “Philosophy” from Klimt and had it installed at the family’s Vienna home. In 1918, he bought the other two canvases, sold “Medicine” to a gallery, and left “Jurisprudence” rolled up in storage.

The three canvases were not united again until 1938. That year, the Nazis rolled into Austria full of pomp and circumstance and destruction as they requisitioned the property, including the great art collections, of Jewish families and devastated lives.

In that year, an exhibition was mounted to celebrate Klimt’s 80th birthday, and the three faculty paintings were brought together to be shown for what would be the last time. Afterwards, they were taken along with the rest of the Lederer Klimt collection to Schloss Immendorf for storage.

Schloss Immendorf was the family home of Baron Rudolf Freudenthal who was given a choice as the Nazis invaded his country: he could either open his doors to to “war refugees,” German soldiers who were fleeing the Russian frontlines, or he could store looted paintings while the Nazi leaders decided where to send them.

In The Lady in Gold, the baron’s son, Johannes Freudenthal, remembers the day in 1943 when he was 10 years old and watched a bunch of strangers move boxes into his castle, stacking up towers of canvases and hoisting crates up the stairs. He remembers seeing naked women and flowers in bloom, mounted soldiers and a golden apple tree. “These are important paintings, not toys, his father told him sternly.” writes O’Connor. “They were painted by a great Austrian artist, Gustav Klimt. His father told Johannes to leave them alone.”

For two years, Klimt’s great canvases sat collecting dust. But what happened next is something of a mystery.

The prevailing story for many years was that, knowing their army was in retreat and the end was near, Nazi soldiers threw one last bacchanalia at Schloss Immendorf, drinking the baron’s liquor supplies and sending any remaining house staff fleeing for their lives.

The next day, they left, but one lone soldier pedaled back on his bike and disappeared into the house. Minutes after he remounted and rode off, the home went up in flames, thus destroying some of the evidence of Nazi crimes and complying with the now-dead Hitler’s Nero Decree.

But another story recounted by Nebehay after he consulted with the now-grown Freudenthal is that the castle and its precious contents survived the German retreat. When the Russians arrived, they took up residence, and, while they were resting, “fire broke out, first in one tower before spreading to the other three.”

With no help from the Russians, the fire was put out, but the conflagration was repeated the next day. Whatever the cause of the fire, this second occurrence raged out of control and decimated the house and its contents.

“Once everything was over and the owners could at last reenter the rooms, an unforgettable sight met their eyes: the great canvasses were blackened, but with some imagination and effort one could still discern the outlines of the figures,” Nebehey says an elderly woman, “presumably Baron Freudenthal’s mother” told him. “Then a draught blew onto these sad remains, causing them to flutter slowly to the floor in a kind of rain of ashes. She said the sight was heartbreaking.”

With that, the Lederer collection of Klimt paintings, one of the greatest private collections of the artist’s work, was reduced to ash.

Regardless of which side of the war was responsible, the end result was clear: some of Klimt’s best paintings had been destroyed, victims of the war that had wreaked such devastation across the continent and that still sends ripple effects through the art world today.