Over the next few weeks, we’re going to hear a lot about what “Barbenheimer” really means for the film industry. One movie massively exceeding expectations is, these days, a major event. But two over a single weekend? Barbie and Oppenheimer—the yin-and-yang hits of this summer movie season, radically different spectacles united through the unexpected good luck of concurrent release—will surely inspire a lot of reactive thinking on the part of studios hoping to replicate the phenomenon of their joint success. If Hollywood learns any lessons from Barbenheimer, however, it’ll probably be the wrong ones.

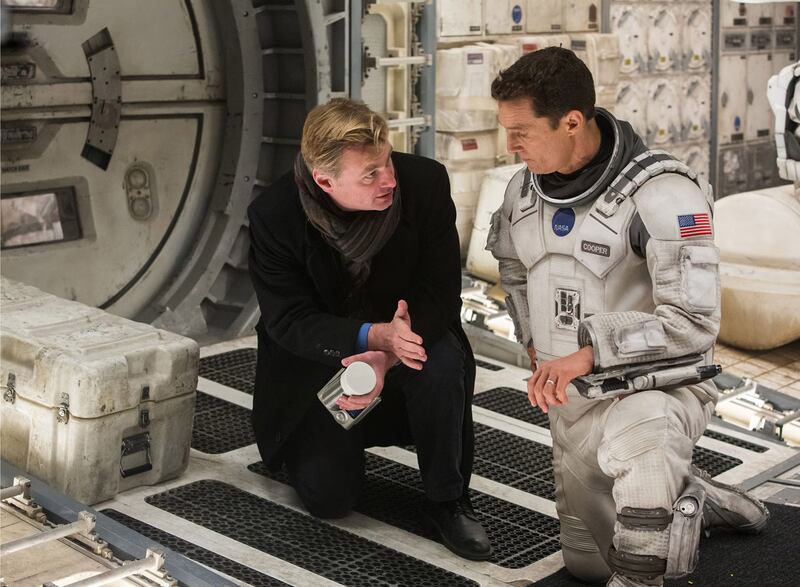

One of the simplest takeaways of this past weekend is more of a forceful reminder of something that should be conventional wisdom, even gospel for executives by now: Christopher Nolan, the writer, director, producer, and reigning blockbuster visionary of our age, can turn just about anything into a hit. Oppenheimer, much more so than Barbie, is the traditional definition of a tough sell. It’s a three-hour drama about quantum physics and McCarthyism, a summer movie set in laboratories and courtrooms; it’s a true gabfest blown up to IMAX proportions. Movies like this don’t make big money, especially not in 2023. Except, apparently, when they have Nolan’s name on them.

Oppenheimer, which opened to a staggering $80 million domestically last weekend, doesn’t simply count as another smash in a career full of them. It also feels like a culmination of Nolan’s whole deal: his heartening, unfashionable tendency to respect the intelligence of his audience. Cinephiles may debate how truly "deep" his blockbusters are, but there’s no denying that almost all of them are conceptually audacious, applying complicated structural gimmicks to their narratives and traipsing into matters of theoretical science. Nolan trusts viewers to keep up with the pretzel logic of his movies. Remarkably, those viewers have rewarded his trust over and over again, by coming out in droves to each new picture, undeterred—maybe even exhilarated—by the very real possibility that it will require some intellectual labor.

Tracing the arc of Nolan’s career backwards, Memento-style, takes you to the origins of his reputation for crafting uncommonly brainy blockbusters: 2008’s The Dark Knight, still the biggest hit he’s ever helmed. The success of that magisterial superhero movie, the middle chapter of his seminal Batman trilogy, wrote a blank check that he’s been cashing ever since. The movie was such a sensation—not just a record-breaking box-office juggernaut, but one of those rare films that seems to dominate the entire pop-cultural attention span for months on end—that it all but guaranteed its maker some runway, the ability to chase his muse out of the franchise trenches.

More than simply buying him that leeway, The Dark Knight also made Nolan one of the few Hollywood filmmakers that can be called a household name. He used the plum gig to assert his interests and personality—to tell the world, through the big stage of a big event picture, that this is what you could expect from a Christopher Nolan movie. His later films would push further into his particular obsessions, but the funneling of big ideas through IMAX-scaled entertainment begins with The Dark Knight. It’s a comic-book movie about chaos and order, cause and effect, and whether ends justify means—a Batman movie that sells the vision of its filmmaker as much as it sells Batman.

Arriving between this historic success and the less rapturously received closing chapter of the Dark Knight saga, Inception was the true test of Nolan’s stature—and the movie that solidified his standing as a reliable purveyor of big-idea blockbusters, the thinking man’s Hollywood hitmaker. "From the writer-director of The Dark Knight" may have put asses in seats, but his follow-up’s runaway popularity dispelled any concerns that Nolan was a flash in the pan, that his powers might weaken beyond Gotham City limits. Without the safety net of beloved intellectual property, the director thrust audiences into a heist movie of M.C. Escher complexity: a brain-bending sci-fi action picture that layered its dream reality like nesting dolls, daring audiences to keep track of multiple planes of dilemma unfolding at different speeds.

The convoluted nature of Inception’s plotting would inspire lots of jokes at its expense (Dan Harmon had a field day), but it wouldn’t hurt the movie. Quite to the contrary, that byzantine structure made it a must-see in summer 2010, amassing fans with each sold-out screening. What became clear quickly was that viewers weren’t putting up with the bewildering-but-plainly thought-out zig zag of Nolan’s storytelling as a tradeoff for the more conventional pleasures, the zero-gravity fights and city-folding special-effects shots. They were actually feeding on the brain candy Nolan provided, getting hooked on the way he sent their minds racing to keep up with the implications of the premise.

Inception, with its twisty temporal mechanics and teasingly ambiguous ending, made Nolan into his own brand, nearly as bankable as that of the masked superhero he sent into action once more afterwards. His name became a promise of a certain kind of rare theatrical experience: a big-budget contraption that would buzz the brain as surely as it quickened the pulse. In the years after, Nolan would continue to issue comprehension challenges to his audiences, and those audiences would continue to rise to them every time. He didn’t need a blank check anymore; each new hit paid for the next one.

2014’s Interstellar is a gushy, all-the-feels space odyssey built on a foundation of hard science fiction. The film tells a tender father-daughter story through the lens of time’s cruel relativity and with a lot of dense jargon. Dunkirk, released in 2017, is a war film of rare immediacy, reducing WWII to a series of ticking-clock, life-and-death scenarios by air, land, and sea. It also happens to take the Matryoshka games of Inception even further, crosscutting the timeline into three distinct stories—one set over roughly a week, another set over a day, and the last set over a single hour, all converging at the exact same point in time and space. And 2020’s Tenet might be the most proudly, stubbornly confounding exercise in espionage action ever inflicted upon moviegoers: The film’s Rubik’s Cube inscrutability begins with its very conceit—the inversion of cause and effect on which the increasingly befuddling time-travel hijinks all rest.

Again, whether Nolan’s movies are as smart as his biggest fans insist they are is a matter of opinion, and irrelevant besides. They are undeniably cerebral in basic shape, especially for movies of their budget. More importantly, they don’t hold the viewer’s hand or over-explain themselves; they count on us to work out their loopy structural games, and to keep pace with the way they fold into themselves. That just about all of them have been big hits—Tenet, the exception, has the excuse of opening in the throes of the pandemic, an unwise decision for multiple reasons—is proof that Nolan has turned the promise of a mental workout into a selling point. At this point, people go to his films with the expectation, maybe even the hope, that they’ll have to work out what they’re seeing. His movies make you feel smart for keeping up.

Oppenheimer might be the ultimate consummation of that special relationship between director and fanbase. It’s a new benchmark in Nolan’s ongoing project to treat the multiplex masses like adults, intellectually capable and curious. Beyond its inherently heady subject matter, Oppenheimer is another structural wonder, applying a sophisticated nonlinear framework to historical events. This time, Nolan takes his cues from actual scientific theory, coding the separate timelines in color and black-and-white, but also with the words “fission” and “fusion”—a choice with all kinds of fascinating interpretative potential. Oppenheimer wants us to grasp the race for the atomic bomb in scientific, historical, political, and moral terms all at once. That big opening weekend suggests that plenty are at least game to try and follow his train of thought.

And that’s worth celebrating in an era when the American box office is mostly dominated by movies that treat all audiences like children. Pick a year, any year in recent memory, and its biggest hits will almost invariably be aimed at all ages; our theaters are now the almost-exclusive dominion of superheroes, cartoon mascots, and other figures of juvenilia. In fact, for all the money they’ve made so far, Barbie and Oppenheimer have a long road ahead of them if they hope to surpass the year’s true box-office winner, The Super Mario Bros. Movie—the epitome of how the studios have child-proofed their dream factory.

Love or hate his movies, Nolan is an anomaly in the field, a thinker who looks out into the dark of the proverbial auditorium and sees a mirror of his own intellectual hunger. For all the grimness of the future Oppenheimer finds in the aftermath of its subject’s achievement, it counts as a hopeful vision in another respect. Once more, Nolan has shown that he believes in a market for grownup entertainment. And once more, the American moviegoing public has justified that faith.