Have the Orange County district attorney’s office and its sheriff been lying about a secret jailhouse informant program, which they’ve allegedly used for years to extract highly dubious confessions?

That’s what a group of 31 law professors and former prosecutors are claiming—they say countless cases have been affected, and they want the Department of Justice to intervene.

The alleged misconduct is so extreme that, after reviewing thousands of pages of evidence, a superior court judge barred all 250 Orange County prosecutors from being involved in a high-profile murder case.

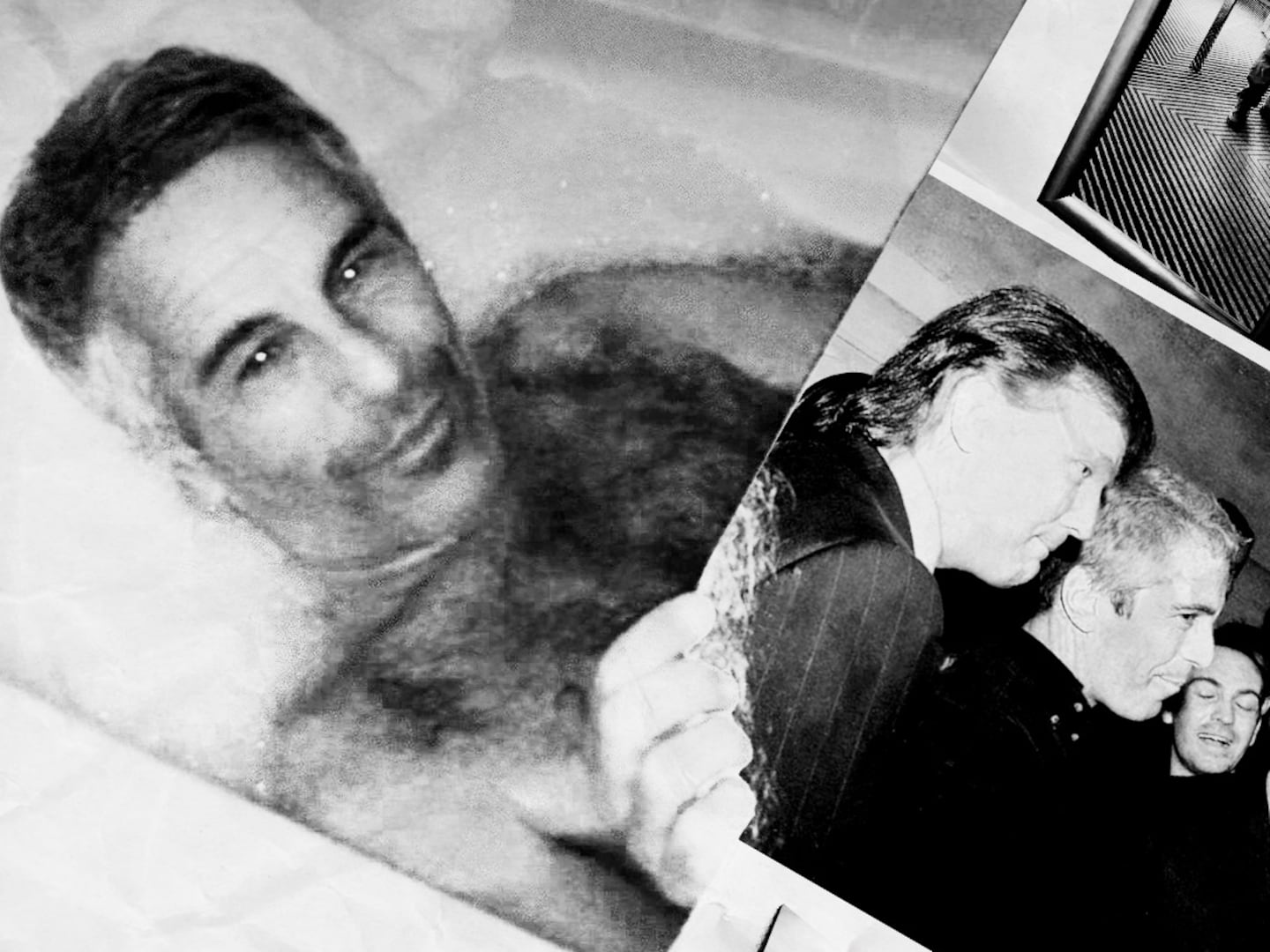

That case should have been a slam-dunk for the DA: The defendant, Scott Dekraai, was convicted of shooting eight people in a bloody 2011 rampage. But in the penalty phase of the trial, the prosecution submitted a jailhouse confession that Dekraai gave to a fellow inmate named Fernando Perez. Turns out, Perez was a serial informant for the DA’s office and had been moved from jail to jail specifically to obtain confessions, according to a ruling by Judge Thomas M. Goethals of the Superior Court of California in Orange County.

That alone is against the law. Informants are meant to be passive listeners, not investigators. But according to the court, Orange County’s misconduct went deeper: Perez was known to be a serial informant who worked by “ingratiating himself with a target suspect and thereafter obtaining incriminating statements,” and the DA never mentioned that fact. It also never mentioned the existence of the informant program in general.

If true, such misconduct would violate the so-called Brady Rule, named after the Supreme Court case that requires prosecutors to disclose potentially exculpatory evidence. And if this misconduct has been going on for the decade or so that the informant program has been in existence, unreliable confessions may have been introduced at dozens of trials over the years.

But because no investigation of the alleged misconduct has taken place, we have no idea of its full extent.

That’s why the bipartisan group of professors and prosecutors has demanded an investigation of the Orange County DA. The group is led by University of California Irvine Dean Erwin Chemerinsky and former California Attorney General John Van de Kamp. Chemerinsky told The Daily Beast: “The most important thing is what we still don’t know. We really don’t know how many cases are tainted, how many informants were used improperly, how often [the] DA’s office failed its Brady obligations and didn’t turn over evidence.”

In the Dekraai case, the Orange County sheriff’s department at first denied that it had placed Perez in proximity to Dekraai. On Aug. 4, 2014, the judge in the case held that the informer Perez and Dekraai just happened to be near each other in jail due to “a confluence of independent events.”

But then came the smoking gun: The public defender’s office introduced evidence of the informant database, maintained by the sheriff’s department, which tracked inmates, movements, and transfers. The sheriff’s department had said such a list didn’t exist.

In his supplementary ruling, issued March 12, 2015, the judge wrote that that someone from either the sheriff’s department or the district attorney’s office had “lied.”

That’s when the judge recused the entire district attorney’s office from the case, a nearly unprecedented move that made headlines.

That case is still going. But the jail-informant database dates back two decades. How many cases have been affected? And who is responsible for it? According to the sheriff, “the District Attorney’s office has known about it for years.” According to the DA, the office only found out about it when the judge did. Clearly, someone is not telling the truth.

The most obvious potential victims are those serving time on the basis of dubious jailhouse informants. But as described in a Nov. 17 letter sent by Chemerinsky and 30 other signatories to the Department of Justice, there is a second, hidden group: victims of unpunished crimes.

For example, one informant, Oscar Moriel, testified that he had committed “up to five, maybe six” murders—none were investigated. And as a result of alleged prosecutorial misconduct, one convicted murderer had his sentence reduced from life without parole to less than four years in jail.

The California attorney general has authority over the Orange County DA’s office, and so might be expected to investigate the allegations of misconduct. However, it has instead appealed Judge Goethals’s ruling, arguing that neither the DA nor the sheriff’s department has committed any misconduct at all.

And a five-person Orange County committee created to make policy recommendations on the issue includes two individuals on the DA’s payroll and is only mandated to make future recommendations, not investigate past misconduct.

Which is why Chemerinsky, Van de Kamp, former Los Angeles County DA Gil Garcetti, and 28 other prosecutors and legal academics have asked the Justice Department to intervene. “I don’t trust an office to investigate itself,” Chemerinsky said.

Susan Kang Schroeder, chief of staff at the Orange County District Attorney’s Office, told The Daily Beast that “we’re open to anyone coming in and reviewing anything that we have done and giving us input. I wouldn’t call it an investigation… Basically, you know, we would welcome anyone to come and review our best practices and any changes we should make in how we conduct ourselves and how the rest of Orange County law enforcement conducts ourselves. We welcome that. There’s no secret.”

But Schroeder said Chemerinsky “doesn’t know the facts” of the Dekraai case in particular. I asked Schroeder to name specific factual errors in the Chemerinsky-Van de Kamp letter, and she said, “Pretty much a lot of it. He cites Judge Goethals’s opinion taking us off the case. But Judge Goethals specifically found that no one in the DA’s office did anything intentionally, had any intentional misconduct, he specifically found that.”

Schroeder also noted that the informant program was a federal program. Many years ago, she explained, “we were having race riots and Mexican mafia riots being run out of the local jails. A lot of people were put on a kill list, a shot list, both inside and outside of jail, and so the federal government came in to quell that violence. That’s how the informant program began.”

Of course, the alleged misconduct that caused the DA’s office to be recused is not about whether the program is federal or state but about the DA’s failure to disclose its use of it.

“My question to Professor Chemerinsky,” Schroeder said, “is why he didn’t hew to his own ethical standards that before opining, you have to get the facts. Even if it’s not his ethical standard that he needed to be there gavel to gavel, he had the ethical standard that he needed to at least learn the facts. Not only did he not know the facts, he refused to learn the facts.”

Specifically, Schroeder said, “We invited him to talk to him personally and made ourselves available to further information. We gave him the same invitation we gave three other law schools to go where we put on a forum and basically explain in public what happened. Three other law schools have taken us up on the invitation, except for Professor Chemerinsky.”

“I have no idea what she’s talking about,” Chemerinsky said. “I have no recollection of that.”

The law schools that did attend the forum, Schroeder said, were Whittier Law School, Chapman Law School, and Western State Law School. Signing the Chemerinsky-Van de Kamp letter were professors from American University, Boston College, Cardozo, Fordham, Georgetown, Harvard, Loyola, Northeastern, Pace, Penn, Santa Clara, Temple, UCLA, UC-Berkeley, UC-Davis, UC-Irvine, University of Mississippi, University of Virginia, Washington University, and Whittier Law School.

Meanwhile, the Department of Justice had already told the Orange County DA that it has opened a file on the matter, even before last week’s letter. It may well conduct the kind of investigation Chemerinsky is advocating. Or it may wait for the California attorney general’s process, and the Orange County process, to play out first. Or it may well do nothing.

Thanks to prosecutorial immunity, it’s unlikely that anyone in the DA’s office will face charges, if misconduct is in fact established. Both the DA and the sheriff are elected officials, leaving it to voters to decide—and voters tend to reward law enforcement officials who are “tough on crime,” regardless of allegations of unethical conduct. Proposals from academics and jurists for prosecutors to have “open files”—i.e., evidence files available to the defense as well as the prosecution—or limiting the use of jailhouse informants have, so far, yet to be implemented.