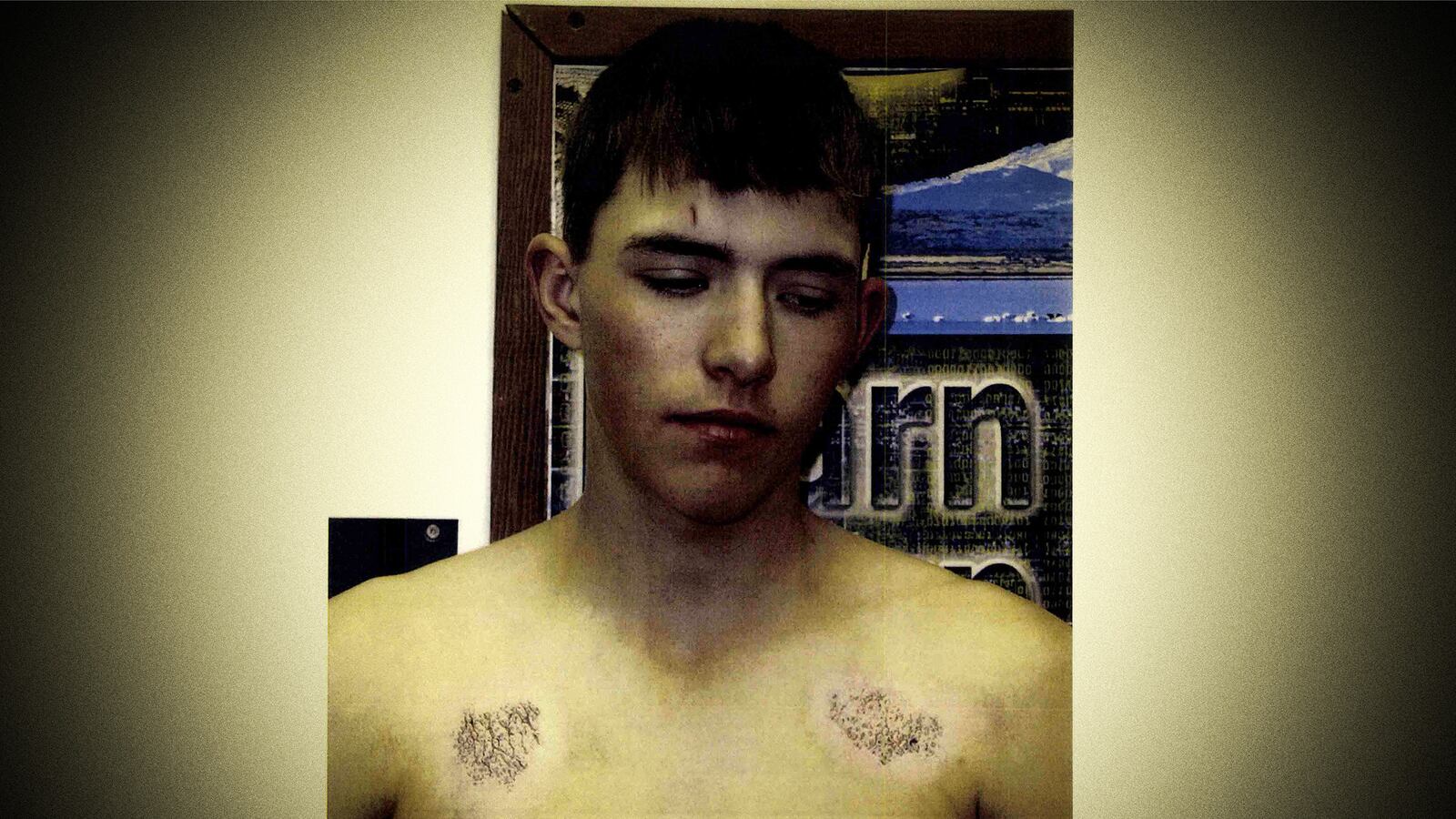

A photo of a teenage boy with two bizarre wounds on his chest suggests that child abuser might be a better description than hero for the two ranchers in whose name so-called militia members have taken over a federal building in Oregon.

“Raising kids is like raising cows or dogs,” one of the ranchers is quoted as saying in a police report to which the photo is attached.

The photo is of Dusty Hammond, nephew of rancher Steve Hammond and grandson of rancher Dwight Hammond.

Dusty was 16 on that March morning in 2004, when Deputy Sheriff Brian Needham of the Harney County Sheriff’s Office responded with a human services representative to Crane High School in the Oregon town of the same name. Needham spoke to Dusty about “a possible assault involving a student.”

“Dusty told me that about four to five weeks ago he had scratched some initials into his shoulder/chest area with a paper clip,” Needham’s subsequent report reads.

The boy’s grandfather, Dwight Hammond, and grandmother, Susan Hammond, had learned about the scratching.

“His grandparents did not know how to handle the situation with Dusty, so they called Dusty’s uncle, Steve Hammond,” the report says. “Dusty told me that Steve is the one that disciplines him on any matters that his grandparents do not know how to handle.”

The report goes on, “Dusty told me that in the past several months the discipline has gotten worse and worse. Dusty told me that two to three months ago he and Steve had gotten into an argument about how Dusty was doing his chores. Dusty stated that Steve became very upset and charged him. Dusty stated that Steve hit him in the chest with a closed fist, knocking him to the ground. Dusty stated that Steve then took Dusty’s face and rubbed it into the gravel. Dusty stated that this action hurt and made him fearful of Steve.”

The report describes Steve as 35 years old, 6-foot-2 and 200 pounds. The report says that when Dusty was caught with alcohol, Steve had driven him at least 10 miles from the ranch “and made Dusty walk back.”

The report further states that when Dusty was caught with tobacco, “Steve made him eat two cans of Skoal Smokeless tobacco, then again drove him 10 miles from the ranch and made him walk back.”

On Feb. 29, 2004, there came the incident involving the initials that Dusty had scratched into his chest.

“Dusty stated that Steve was very upset with him,” the report says. “Dusty told me his grandparents were present during the time.”

The report continues, “Dusty stated that Steve told him that he was not going to let Dusty deface the family by carving on himself. Dusty stated that Steve then took him and began to sand the initials off his chest… Steve sanded on each side of his chest for at least five minutes… Steve used a very coarse sandpaper to sand off the initials.”

The report goes on, “Dusty told me that the process was very painful, but that he did not cry because he knew that Steve would continue the process for a longer period of time.”

The report says that by Dusty’s account, the grandmother was in the room the whole time, but the grandfather got up and left halfway through. Steve kept sanding.

“Dusty told me that Steve told him that if the sanding did not remove the initials, that he would fillet the initials off Dusty’s chest,” the report says.

The sandpaper did the job.

“Dusty told me that after Steve was finished with the sanding process, that the areas were bleeding,” the report states. “Dusty told me that his grandmother told Dusty to clean the area up and not to have a pity party.”

The report further recounts, “His grandmother told him to shower if he wanted to, but to make sure that he cleaned the wounds with alcohol and put Neosporin on them. Dusty told me that he did as his grandmother instructed and then went to bed.”

The wounds were still raw when they came to the attention of the school 10 days later, on March 9. The human services official, Sandy Gardner, photographed the boy’s injuries in Needham’s presence.

A week later, on March 16, Needham interviewed the Hammonds at their ranch. Needham asked to record the interview, but the Hammonds told him they preferred that he not. He read them their Miranda rights.

“I asked everyone if they could tell me what had happened on or about February 29, 2004, when the sanding incident with Dusty Hammond occurred,” the subsequent report on this interview says. “Steven Hammond began by telling me some background information concerning Dusty Hammond.”

The grandparents joined in, telling Needham that they had had custody of Dusty for about four years, since 2000. They had begun having trouble with him in September 2003, they said. They had sought help at the county behavioral health center, and the boy had been put on “a medication similar to Prozac for about the last three or four months.”

“This conversation went on for about fifteen to 20 minutes before I finally got them redirected,” the report says.

The deputy asked the Hammonds about the time Dusty had been caught with alcohol and Steve allegedly forced him to walk 10 miles back to the ranch.

“The Hammonds changed the subject and would not answer the question,” the report says.

Needham then inquired about the time Dusty had been caught with tobacco.

“Dwight told me he tried to show Dusty that chewing tobacco was harmful on his body,” the report says. “Dwight continued by saying that he had Dusty eat a full can of chewing tobacco over a several day period.”

Needham asked about that 10-mile trek back to the ranch.

“The Hammonds changed the subject and would not answer my question,” the report says. “I moved to the sanding incident.”

Then came the line that would stay with anybody who read it.

“Steve Hammond began by telling me that raising kids is like raising cows or dogs,” the report says.

As recounted in the report, Steve proceeded to suggest that Dusty would have suffered a lot worse if they had gotten their hands on him after he told the authorities how he got his twin wounds.

“Steve then told me that Dusty was lucky that he was not at the ranch when he told on Dwight, Susie, and himself, or there would have been hell to pay and Dusty would have wished he wasn’t alive,” the report says. “I explained to the Hammonds that it was not Dusty that was pursuing this investigation, that it was the State of Oregon. Steve Hammond told me that he did not agree with the government getting involved in family matters.”

Needham returned the discussion to “the sanding incident.”

“Dwight Hammond told me that Dusty had accidentally showed him the carvings of the initials on his chest, that a family meeting was called to discuss the incident,” the report says. “Dwight told me that Dusty was given an opportunity to come up with an alternative punishment. Dwight told me that after a while, when Dusty was not able to come up with a punishment, that it was decided that the initials would be sanded off.”

The Hammonds told Needham that “it was decided mutually and agreed upon by everyone including Dusty that this was a good plan.”

“Steve Hammond told me that they have been trying to teach Dusty to respect his body,” the report says. “During the interview, I asked approximately 10 times who actually did the sanding on Dusty’s chest. But no one would ever tell me. The Hammonds continued to change the subject when asked.”

As recounted in the report, the Hammonds then suggested that Dusty himself was responsible for the severity of the wounds.

“The Hammonds told me that after the sanding was completed, Dusty made the comment that he did not think the areas were sanded deep enough and thought that he should use steel wool to sand the areas some more.”

Really.

The report continues, “The Hammonds told me that they do not know if he actually sanded the areas any more…The Hammonds told me that none of them saw the injuries after that time. The Hammonds did not have anything else to add.”

Even though someone who treats a dog, not to mention a kid, this way could have been arrested, the Hammonds do not seem to have been charged. Dusty returned to living with his mother, then his father, then his mother again.

According to court papers, Dusty told the government investigators who interviewed him five years later that he had been in mortal dread of his uncle.

“When interviewed by federal agents, the 21-year-old Dusty Hammond said he feared that when Steven Hammond learned he had talked to police that Steven would come to his front door and kill him,” the papers said.

The federal agents had come to ask Dusty about fires they believed his uncle and grandfather had set on government-owned land adjacent to the ranch. Dusty told them a story from when he was 13 and going on his first deer hunt. He repeated this account before a federal grand jury and again from the witness stand when his uncle and grandfather were tried for arson.

Dusty said he had heard a number of gunshots after the others in the hunting party proceeded over the top of a hill but that he had neither fired his rifle nor seen any deer. He did see what his uncle distributed at the end of the hunt.

“Steven started handing out boxes of Strike Anywhere matches and said, ‘We’re going to light up the whole country on fire,’” Dusty told the jury.

He said Steve had pointed to a spot on the skyline and told him to head there.

“Just said, ‘Start lighting them and walk in that direction until you run out,’” Dusty testified.

Dusty did as bid, dropping lighted matches into the grass as he went while his uncle and grandfather and others in the party did the same in different directions. He ran out of matches and was turning to rejoin the others when he realized he was surrounded by flames.

“Fire was like knee high to start with, and then it—I was looking, trying to figure out where everybody else went, and I kind of got, like, trapped by it,” he testified. “It came up behind me faster than I expected it to… It was, like, over my head, eight, 10 feet probably… I thought I was going to get burned up.”

He dashed down the hill to a rocky stream, he said.

“There was Mud Creek, just a little bit of water, not much, but everything was green around it, so I went down there in the rocks and waited for most of [the fire] to go by,” he testified.

Dusty eventually reached his grandfather’s pickup truck, he said, and rode back to the ranch. They all sat down to a lunch of egg salad sandwiches.

“Dwight told me to keep my mouth shut, that nobody needed to know about the fire,” Dusty testified.

The prosecutor asked why he had remained silent even long after he was away from the ranch living with his mother.

“I was afraid of Steven and Susie,” he testified. “And I don’t like to talk about it. Just never said anything about it. Nobody ever asked.”

“Someone eventually did ask, did they not?” the prosecutor inquired.

“Yeah,” Dusty replied

“In March of 2011?”

“Yes… There were two of them that come up.”

He was speaking of the federal agents.

“Did you tell [the agents] what you’ve been telling the jury today?”

“Yes.”

“Why?”

“Because [they] asked. And I’m not afraid of [Steve] anymore.”

Dusty further testified that his uncle and grandfather had gone up in a private plane later in the day.

“Said they were going to go fly over and see what the fire did, and see if they got rid of the juniper trees and something else,” Duty testified.

The Hammonds would later admit to setting a number of fires, saying they had only been doing so as a precaution against a much larger wildfire sweeping through. The government would contend that the “something else” they hoped had been burned was any evidence that they had been poaching deer on federal land. They are said to have become concerned when a group of other hunters happened to see them.

The jury convicted the uncle and grandfather of arson on federal property. A counterterrorism statute mandates a five-year minimum term for the crime, but federal Judge Michael Hogan declared that in these circumstances “it would be a sentence which would shock the conscience.”

The judge sentenced Steve to a year and a day, Dwight to three months. The government appealed and won in 2014.

“Even a fire in a remote area has the potential to spread to more populated areas, threaten local property and residents, or endanger the firefighters called to battle the blaze,” the appeals court held. “Given the seriousness of arson, a five-year sentence is not grossly disproportionate to the offense.”

As re-sentencing neared, the Hammonds submitted a Sept. 30, 2015, letter to the court in which they described themselves as “dedicated men who are highly regarded in their community.”

The government noted in a sentencing memorandum that the Hammonds “omit any mention of their alleged assault and abuse of their sixteen-year-old grandson/nephew Dusty Hammond.” The photo of the twin wounds was entered into evidence along with Deputy Sheriff Neeham’s reports.

The Hammonds were sentenced to the mandatory minimum of five years but given until after the holidays to surrender. The designated date was Jan. 4, the first Monday of the New Year.

As the time neared, armed members of a so-called militia took over a federal building in supposed solidarity with the Hammonds. Steve and Dwight had the sense to say the deluded attention seekers did not speak for them.

On Monday, the Hammonds did indeed surrender. They could not be reached for comment. Nor could Dusty.

The militia members continue their occupation, insisting they do so in the name of two ranchers they call heroes but might be better described as child abusers.