The sight of the former welterweight champion of the world dressed in fishnet stockings and high heels creates a certain cognitive puzzle. What accounts for this desire?

And yet, this week, retired boxing legend and tycoon Oscar De La Hoya has been back in the news for a second go-round of accusations that suggest he’s a part-time cross-dresser.

Angelica Cecora, a 25-year-old model, has accused the retired boxer of forcing her and her roommate into a night of coercive kinkiness.

“Things that I don’t even know how to explain were done with him,” she told the New York Post.

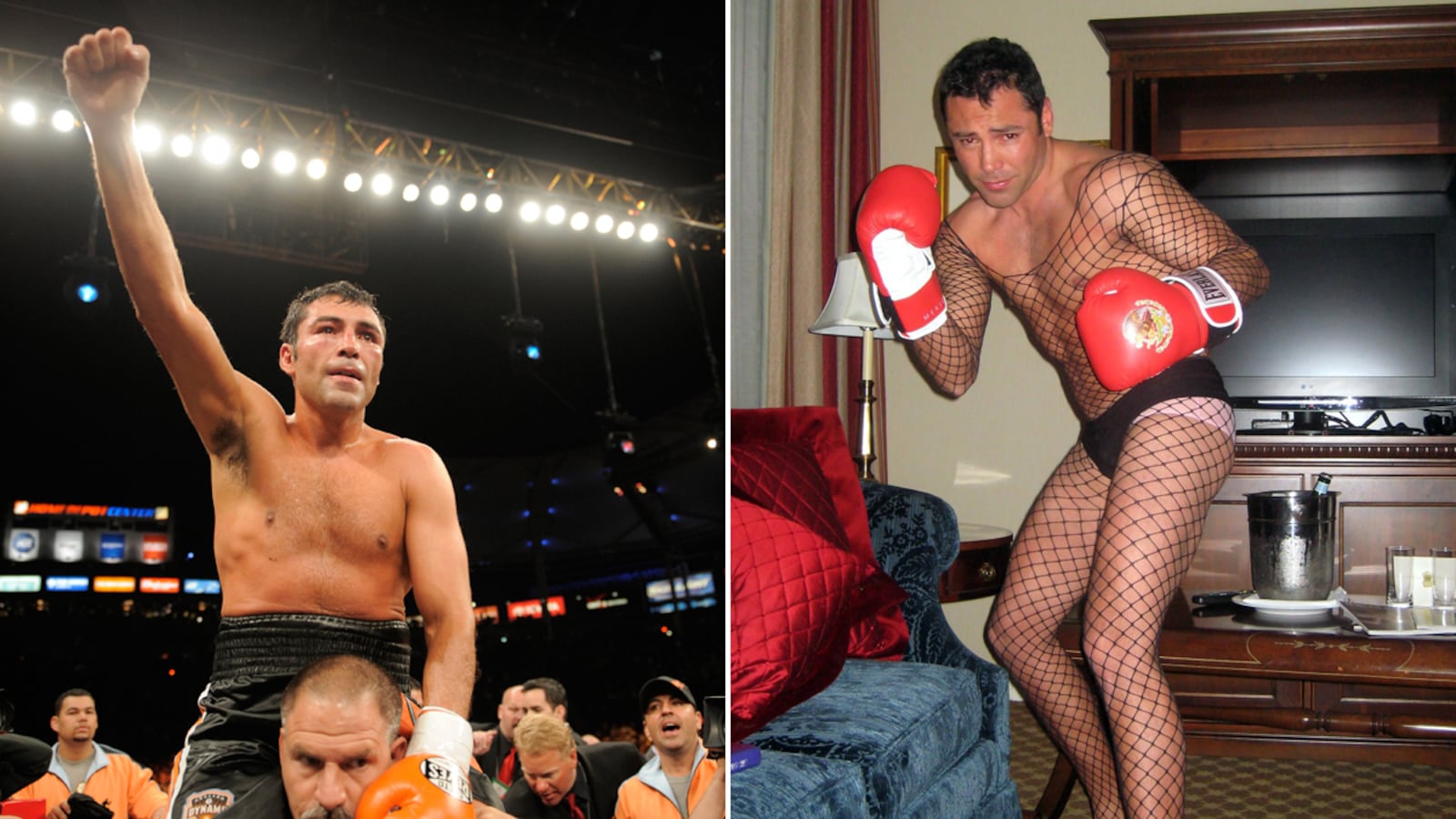

For De La Hoya, the first time around this particular block came in 2007, when a spate of photos appeared on the Internet showing him in a fishnet body stocking, black high heels, pink underwear, and a jaunty fedora—among other items—and assuming a variety of stereotypically female sex positions around his hotel room.

Initially, De La Hoya denied the authenticity of the photographs. This year, however, he admitted they were real, but attempted to explain them away, citing an addiction to cocaine and alcohol.

Indeed, the photos of the boxer in stilettos did present a surprise and likely a problem for many of his fans.

On those nights when Oscar De La Hoya becomes Oscar de la Renta, what are we to think?

What might be the driving force behind such an apparently incongruous habit?

Dressing in drag “engages in a form of ambiguous behavior,” says Michael Garfinkle, a psychologist in private practice in New York.

“The whole idea of the striptease is the mystery of what you also know. In some way, when someone dresses in drag, that’s the thing that they’re challenging. That what lies beneath the layers may in fact be the opposite of what you wanted to see there.”

The person who dresses in drag is conscious of the transgressive aspect of what they’re doing; it’s a part of the appeal.

Yet, Garfinkle notes, “if you’re going to do something that makes you feel good, but that also is frowned upon, then it’s decidedly a mixed experience.”

Indeed, the sense that De La Hoya might be having a mixed time of it seems in some of the photos plainly visible in his expression, which reflects some combination of titillation and trepidation.

It is this fear of embarrassment and shame that creates one of the organizing differences between men who are drawn to wearing women’s clothes, says Justin Frank, a Washington, D.C. psychoanalyst and author of the new book Obama on the Couch.

There are men who are completely public about it—think for instance, of former Chicago Bulls player Dennis Rodman, arriving in his trademark lipstick—versus those like De La Hoya, who are doing it only in private, “on business trips, or when no one’s around.”

“The people who do it in private are very often men who want to express the feminine side of themselves, but they’re afraid of being humiliated,” says Frank.

Frank emphasizes that there are countless reasons why cross-dressing could be erotically appealing to the men who do it, but one common thread running through, he says, is the feeling of power that it bestows.

“You can be both man and woman,” says Frank. “It’s a denial of need.”

Nobody else has to be involved. Nobody else is required.

“It provides the same kind of appeal as masturbating does,” says Garfinkle. “In some way, it replicates the experience of someone else doing something.”

Despite common assumptions to the contrary, dressing in drag doesn’t necessarily mean being gay or identifying primarily as a woman.

In fact, according to the current DSM—psychiatry’s official handbook—you must be a heterosexual man in order to receive a diagnosis of “transvestistic fetishism.”

“To Jack Drescher, a psychiatrist and psychoanalyst in New York, the reason for this criteria might be explained by the relatively simple fact that many of the people who have historically come into a psychiatrist’s office for help with their private cross-dressing habits are heterosexual men, who are there because “they’ve been found out,” as he puts it, discovered by a horrified wife or girlfriend.”

Of course, many people now believe that cross-dressing should not be looked upon as a psychiatric disorder, that the notion of labeling it as a pathology is completely obsolete.

“There’s been great debate since the origin of modern psychiatry about how to handle fetishism in general,” says Garfinkle. “Psychiatry long has tried to maintain that transvestitism is a psychiatric disorder. It’s been the work of people who think very carefully about this in the last 20 years or so who’ve really eroded that strong feeling.”

There’s even a kind of innocence about it, Drescher points out. As a fetish, “it’s harmless.” For many, it’s fun, it’s exuberant self-expression.

“Drag allows some people to tap into the glamorous excitement of being a woman,” Drescher says. “They may feel dowdy as men, or not so attractive, but as a woman, they can make themselves more eye-catching and get more attention.”

Drescher notes an ironic parallel.

“It almost has the quality of sport. It’s a lot of work to get oneself in gear ... You need layers of makeup and wigs and jewelry and costume jewelry and things breaking and zippers not closing,” Drescher adds. “Like sports, it’s a lot of background work to do a performance.”

And so we can think back to boxing, the showmanship of it, the charged arrival of the man in the silk robe. The drama of removing that robe.

The question of what’s underneath.