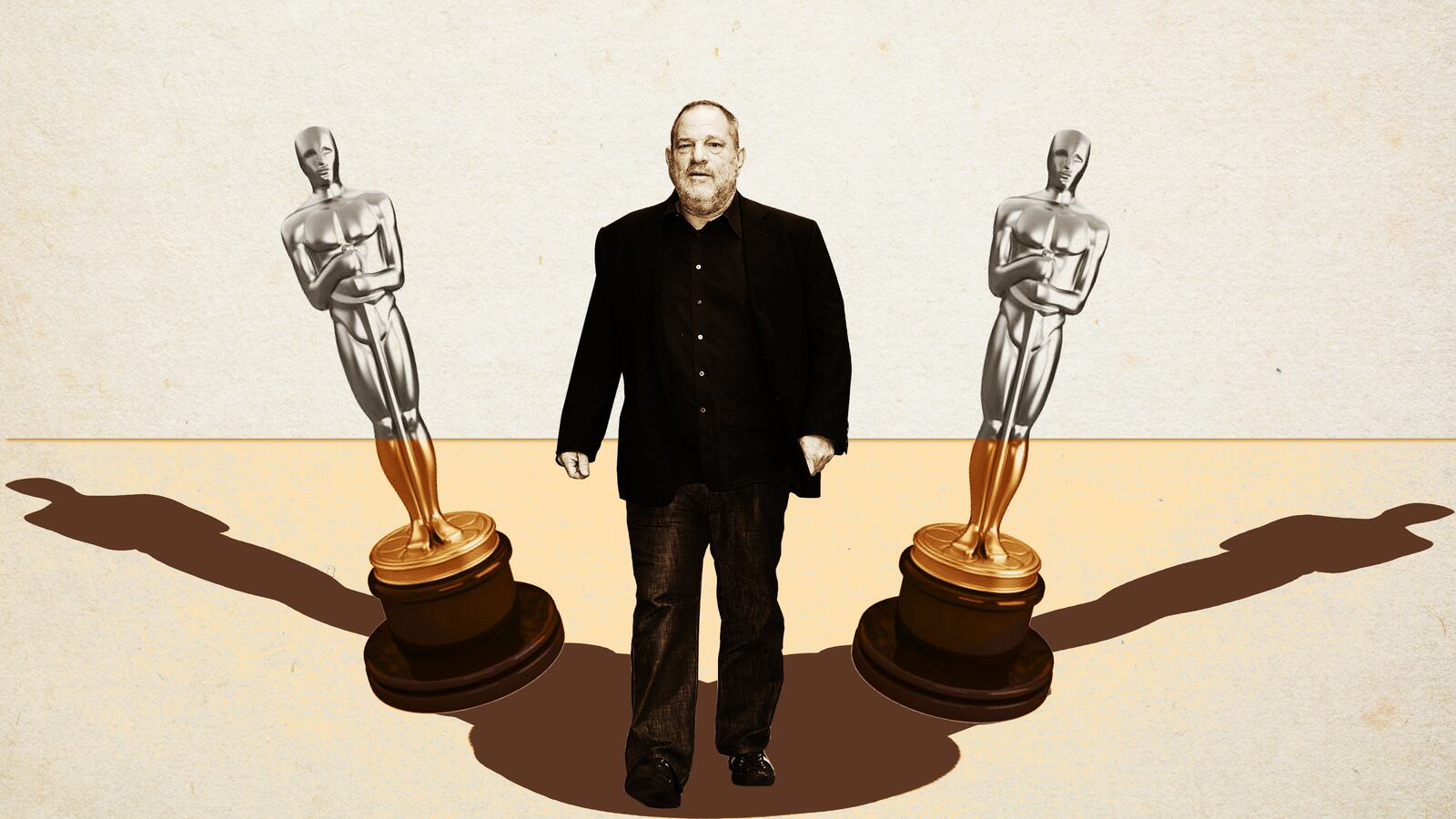

Marlow: Harvey Weinstein has been banished from Hollywood. Good riddance. And with the bully and serial sexual predator went cutthroat Oscar culture, replete with ruthless smear campaigns and the strong-arming of Academy members. Of course, Weinstein didn’t necessarily invent the Oscar smear campaign—he merely put his own, ugly spin on it. For a bit of context, the first major one came courtesy of William Randolph Hearst, the godfather of yellow journalism, who in ’41 launched an all-out assault against Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane, a film based on the media titan.

Kevin: Tell me more!

Marlow: So… Hearst reportedly banned all his newspapers and radio stations in his vast empire from reviewing or even mentioning the film, pressured movie theaters into not showing it, is said to have offered MGM chief Louis B. Mayer $805,000 (over $14 million today) to make it “disappear,” and if all that weren’t enough, Welles went as far as accusing a Hearst reporter of attempting to blackmail him by hiding a 14-year-old girl in his hotel room (with photographers lying in wait). All of Hearst’s machinations ultimately worked, with Kane losing the Best Picture Oscar to John Ford’s How Green Was My Valley—in what many consider the biggest Oscar upset in history. But that was one rich man’s vendetta against a single film. Harvey transformed the entire Oscar landscape.

Kevin: Yes, never forget the infamous stat that Harvey Weinstein was apparently thanked in more Oscars acceptance speeches than God.

Marlow: And was even called “God” by Meryl Streep, albeit at the 2012 Golden Globes. Yikes.

Kevin: He’s now completely changed the Oscars and the way the awards season unfolds twice, albeit the second time unintentionally. The amount of bullying and muscle—not to mention money—he put into Oscars campaigns changed the industry completely, first with Shakespeare in Love’s surprise win over Saving Private Ryan in 1999, and then aggressive pushes on behalf of Chicago, The Aviator, The Reader, The King’s Speech, The Artist, and more.

Marlow: With many of those films (*cough* The King’s Speech) entirely undeserving! #JusticeForTheSocialNetwork.

Kevin: The more vicious and expensive his campaigns were, the more robust rival studios had to be in return, transforming the awards season into a mean-spirited arms race. And now his expulsion from the Academy in the wake of sexual misconduct allegations has changed the game again. It’s not that the strategizing is gone completely, but the outward-facing messaging that the industry wants to telegraph is a cleaner one, and the kinds of projects and themes the Academy hopes to reward and wants the Oscars to represent seem to have galvanized in tandem with the #MeToo movement. More, looking at this past awards season, you could even wonder whether scandals, which once doomed a film’s hopes in the Weinstein days, actually matter at all.

Marlow: It’s fascinating how 20 years ago Weinstein’s Miramax infamously spent $15 million (about $23 million today) to push Shakespeare in Love past Saving Private Ryan for Best Picture, and this year Netflix reportedly shelled out just a tad more—$25 million—for the Oscar campaign to Roma, even though the film only cost $15 million to make. That gamble seems to have paid off, with the film receiving 10 Oscar nominations, including Best Picture. And two years ago, Amazon is said to have spent over $10 million on the awards campaign for Manchester by the Sea (the same amount it cost to acquire it), which also worked, with the film earning four Oscar nominations, including Best Picture (becoming the first streaming service to get a Best Picture nod). So you’re still seeing nascent studios, in this case Netflix and Amazon, pay big money to get in the awards conversation. But yes, the ugliness is gone.

Kevin: Ugliness has no place in Hollywood!

Marlow: And it got really ugly. I mean, who can forget the time Weinstein harassed Sydney Pollack on his deathbed about the awards-courting release plans for The Reader, or this curious piece about veterans being upset with their portrayal in Saving Private Ryan (the year Shakespeare won, of course), or a flurry of reports on Fox News and Drudge questioning the veracity of A Beautiful Mind, from sanitizing its subject’s sexuality to attacking his purported anti-Semitism (Weinstein’s In the Bedroom was competing for Best Picture that year, as was the Weinstein-produced Fellowship of the Ring).

Kevin: Lately, it’s the nominees themselves who are their own worst enemies. The awards season is so long that it’s inevitable there will be public missteps and foot-in-mouth moments. And I wonder if nominees’ pasts are called into question more than ever before, thanks to some damning the-internet-never-forgets archives.

Marlow: Oh, like John Wayne’s very, very infamous Playboy interview, that people somehow managed to dredge up/hadn’t heard of before this week?! This is one of the most well-known celebrity interviews of all time, people. Jesus.

Kevin: Veracity seems to be the constant talking point, with the optics of fudged facts in Bohemian Rhapsody and Green Book so problematic. Yet, by and large, none of these things have seemed to sway voters’ minds, at least not in the same ways they once did—plus, they’re scandals of the filmmakers’ own doing. Have there been any out-and-out smear campaigns this year, do you think? There certainly have been scandals, but I’m not sure there’s been Weinstein-levels of bullying. (Though I wouldn’t be surprised to learn that the ridiculous piece about Bradley Cooper and A Star Is Born that Sean Penn wrote for Deadline was actually planted by a rival film.)

Marlow: Oh God, that essay! And we thought the El Chapo one was bad... But to your larger point, yes, it doesn’t seem as though there have been any studio-engineered smear campaigns at work this year, and certainly no Weinstein-level bullying; rather, it seems like much of the organic backlash against films like Green Book and Bohemian Rhapsody has actually helped those films’ awards chances, with their fans growing ever more entrenched. But hey, at least Harvey’s gone. The actual ceremony, on the other hand, ain’t lookin’ too good.

The 91st Academy Awards will air Feb. 24 on ABC at 8 p.m. EST.