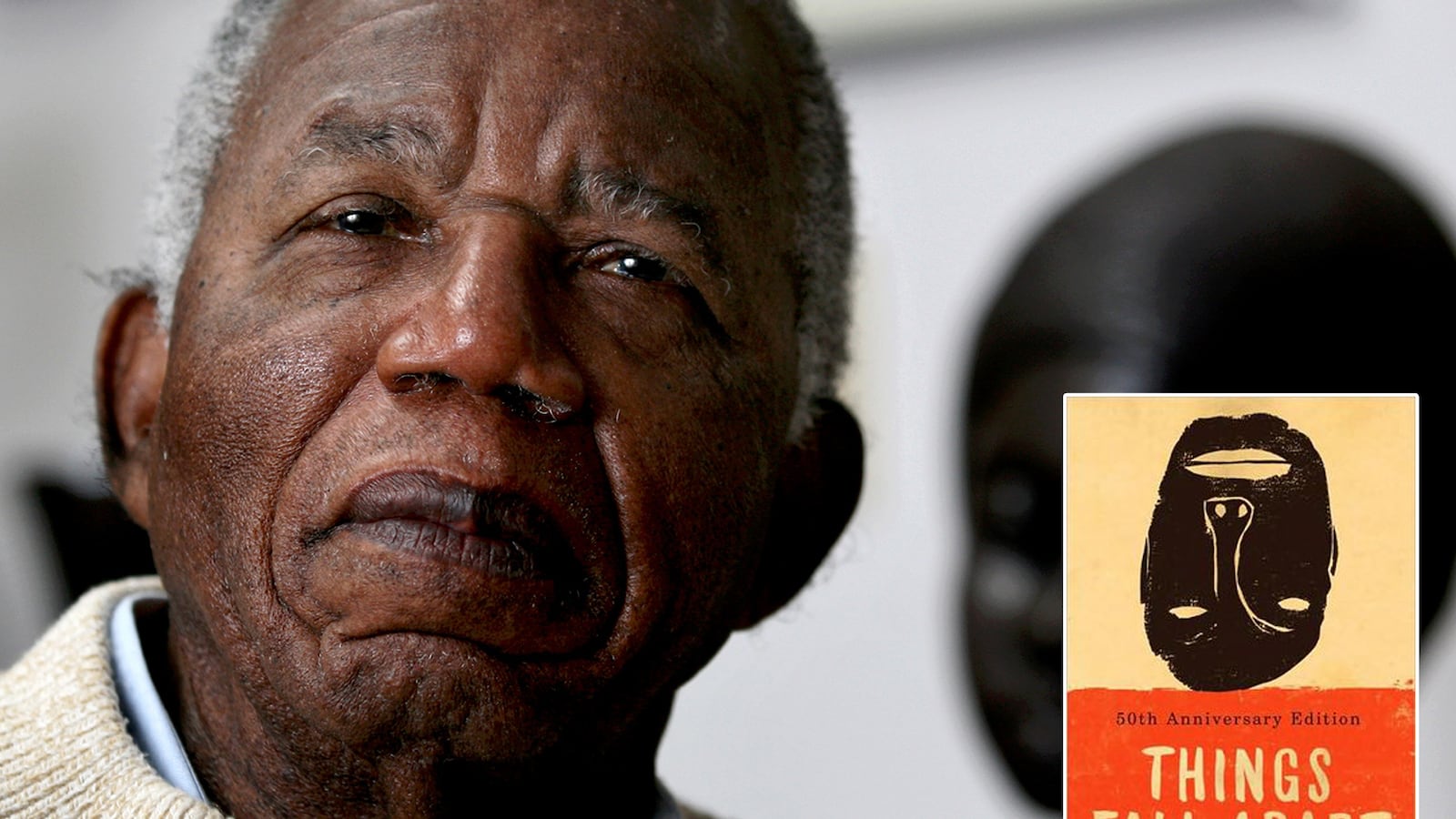

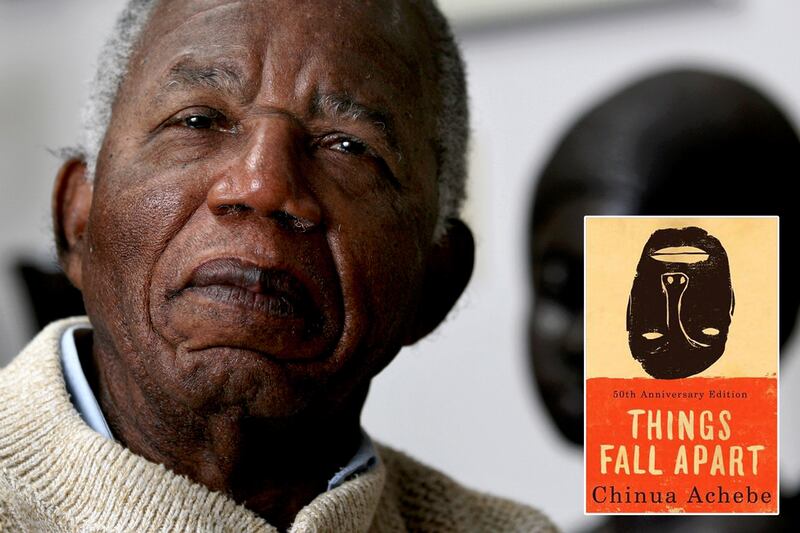

It is five a.m. and for some reason I have awakened and cannot sleep. I pace around my apartment in the cold California dawn. I brew coffee and sit sipping in the kitchen watching the sun come up over my neighbor’s house. I don’t know why I feel so uneasy. I always have this feeling, this waking from deep sleep to unease, when someone I know passes away. Then the call comes from my brother—Chinua Achebe has died.

Chinua Achebe was a well-worn name in my home.

My father knew him from a brief stint working with him for the Biafran Broadcasting Service. While Achebe stayed with the BBS, my father left to head up the relief effort. Post-civil war, my father was the principal of Isienu Secondary School in Nsukka and Achebe was an occasional visitor to our house. Later as my brother became a professor at the University of Nigeria Nsukka, he agreed to pass the manuscript of my first novel to Achebe for feedback. Achebe agreed to look at it when he discovered I was only 15, even though thrillers (my genre at the time) proved unattractive to him.

So in this way, Achebe was with me at the beginning of my writing career. But before even then, as a young boy of 10 I snuck into my elder brother’s room to play his records and try on his shoes and snoop around the way every younger brother does to an elder. Every successful artist comes from a family—parents or siblings or both—who, although equally gifted, chose not to pursue the treacherous and difficult path of the artist. While in my brother’s room I uncovered a hardcover lab notebook filled with the elegant cursive script that was the legacy of a colonial educational system. It was a novel. I sat and read for hours even secreting it out of my brother’s room to read it in my bed that night by the light of a lantern.

I had grown up reading about the Shi’ar Empire and the X Men, the Silver Surfer and Galactus, Enid Blyton’s Famous Five and Secret Seven, the Russian world of Dostoyesky, and watching more American, British, and Australian TV shows than I care to remember, but reading this novel by my brother was riveting—here were my uncles, the double talk of proverbs, the food and masquerades I recognized and even in Okonkwo much of the existential loss of my father’s generation.

When my mother came to turn off the lamp she asked me what I was reading. I told her it was a novel by my brother. She took one look at the first sentence and laughed. It turned out that my brother had copied out the entire Things Fall Apart by hand to impress girls. That says something quite incredible about the power of Achebe’s writing and also the hunger that he clearly understood and addressed. What my brother had done would be equivalent of a contemporary American teenager, in the age of Harry Potter and Twilight, copying out by hand all of Roth’s American Pastoral in a notebook to impress a teenage girl.

This was and remains the alluring power of Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart. That he could write a novel at 28 that could inspire serious scholarship, that would also serve as a powerful enough intervention in the development of the African novel as to change its course, that would be the seminal novel that offered the world African characters with self-awareness and rich inner lives, that would be enough to rivet the attention of a 10 year old and make a 15 year old think that pretending he had written it would make him popular among girls is a feat I don’t think any other novel can claim. This is the reach of Achebe’s work, the reason he is and was beloved by everyone who encountered his work. There is no living African writer who has not had to, or will not have to, contend with Achebe’s work. We are either resisting him—stylistically, politically, or culturally—or we are writing toward him. All of us, writers and readers, have in this singular moment lost our muse. The Igbo say that we only truly die when no one remembers our name, not even our family. Achebe is in no danger of this. He remains a living ancestor.