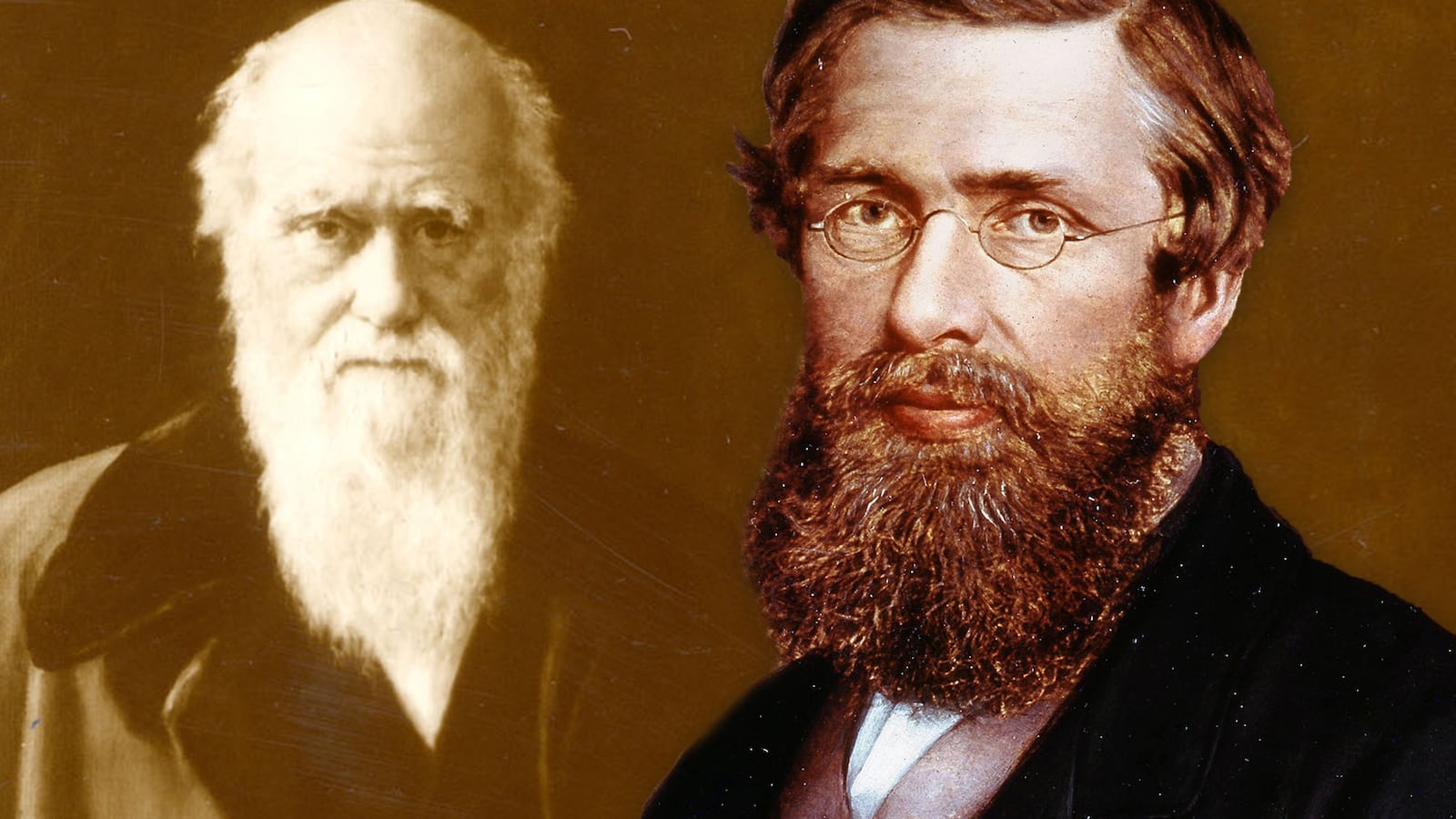

Although Alfred Russel Wallace should be as famous as Charles Darwin for discovering that species evolve – Wallace was evolved enough to delight in Darwin’s glory, not stew in Darwinian jealousy.

Thomas Edison’s one percent inspiration and ninety-nine percent perspiration genius formula got it half right; it’s also 150 percent marketing. Although we imagine lone inventors shouting “Eureka,” most discoveries are three-dimensional, involving colleagues, predecessors—and competitors. Edison should be known as one inventor of the light bulb, along with Joseph Swan, Henry Woodward, Matthew Evans, William Sawyer and Albon Man. In a less pr-centered world, we would think of Elisha Gray and Antonio Meucci, with Alexander Graham Bell’s telephone, Karl Benz with Henry Ford’s motor car, and Alfred Russel Wallace with Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution.

Wallace’s obscurity is so striking because his input was so important yet Darwin’s name is now so dominant. The light bulb isn’t the Edisunlight, the phone is not the Bellaphone and the car is a car, with Ford, Mercedes-Benz and other brands. But the theory is Darwin’s, the school of thought Darwinism, the mode of competition Darwinian.

Yet, in 1858, struggling from a malarial fever in Gilholo—now Halmahera—contemplating Thomas Malthus’s pessimism that disease and famine kill off the weak, Alfred Wallace had his breakthrough. A naturalist who observed keenly, collected obsessively, and wrote exquisitely, Wallace noticed what Darwin noticed: the world is overflowing with species distinguished by subtle variations which represent some natural dynamism.

Wallace thought the differences reflected different environmental adaptations. Darwin emphasized competition, a natural sifting which only the fittest survived. Both embraced heresy: creation was no six-day God-produced melodrama, but a constant process of churning, changing, evolving.

Wallace sent his paper on natural selection to the person he figured would most appreciate it. It was also the individual this middle-class, perennially-financially-strapped naturalist most wanted to impress—the wealthy, well-bred, brilliant aristocrat Charles Darwin.

Wallace “could not have made a better short abstract!” Darwin exclaimed. “Even his terms now stand as heads of my chapters ... he does not say he wishes me to publish, but I shall, of course, at once write and offer to send to any journal.” Darwin added: “I would far rather burn my whole book, than that he or any other man should think that I had behaved in a paltry spirit.”

Feeling protective—and paltry—Darwin’s friends pushed him to write a short introduction summarizing his central insight. The result was On the Origins of the Species, published in 1859. To respect Wallace—while asserting Darwin’s primacy—his colleagues presented Wallace’s paper with two of Darwin’s writings, to the Linnean Society on July 1, 1858.

Hollywood would make the egos clash—Mozart versus Salieri redux. Instead, Wallace demonstrated grace and gratitude. “I sent Mr. Darwin an essay on a subject on which he is now writing a great work,” he wrote. Wallace was flattered that Darwin and his friends “thought so highly of it.” And working his own angle, Wallace told a friend: “This assures me the acquaintance and assistance of these eminent men on my return home.” It did. It also helped him sink into today’s relative obscurity—although he should soar in our estimation.

Still, let us not only judge Alfred Wallace by the impossible standard of competing with Darwinian immortality. Judged on his own merits, he had an impressive career—and left a substantial legacy.

Wallace learned about natural selection during a stunning, eight-year mission in the Malay Archipelago (present-day Singapore, Malaysia, and Indonesia). From 1854 to 1862, traveling 14,000 miles, he collected 125,660 specimens, including, one biographer tallied, “310 mammals, 100 reptiles, 8,050 birds, 7,500 shells, 13,100 butterflies, 83,200 beetles, and 13,400 other insects.” Wallace also identified a defining zoogeographical boundary deemed “The Wallace Line,” and wrote one of the nineteenth-century’s most popular – and still read – works of scientific observation, The Malay Archipelago.

Living as we do on GoogleEarth where you “explore the far reaches of the world, right in your browser,” it’s hard to appreciate just how wonderful it was to have one individual representing Western civilization delighting in one corner of nature—and reporting back to everyone else. Today, our great scientists—physicists—explain unseen mysteries; in the nineteenth century our great scientists—naturalists—chronicled mysteries we could see, if we bothered noticing—or reached some corner of the world.

Published in 1869, Wallace’s Malay Archipelago was a triumph. It marked the culmination of the then-46-year-old’s quite trying life story. Unlike Darwin, Alfred Russel Wallace had to leave school at 13 when his father went broke. Wallace overcame his own bad luck, ranging from a shipwreck which drowned four years’ worth of notes and specimens collected along the Amazon in 1852, to a string of bad investments. At one point, Wallace even had to grade government exams to make money—and edit for some colleagues, including Charles Darwin. Eventually, in 1881, the government granted him a two-hundred-pound annual pension to honor his scientific contributions, thanks to lobbying from influential friends, including Charles Darwin.

Still, the book hit big. The novelist Joseph Conrad called the Malay Archipelago his “favorite bedside companion” and mined it when writing Lord Jim. It reflected Wallace’s reverence for the power of different environments. In founding the field of biogeography, he developed the “Sarawak Law” that “Every species has come into existence coincident both in space and time with a closely allied species.”

And, take that Salieri, Wallace dedicated his classic to Charles Darwin.

Ultimately, Wallace published 22 full-length books and at least 747 essays, 508 of them scientific papers. One biographer estimates that 29 percent covered biogeography and natural history, 27 percent evolutionary theory, and 12 percent anthropology.

Another quarter were social commentary while 7 percent addressed spiritualism and phrenology – the pseudo-science of cranial reading. That’s where Darwin and Wallace parted. Wallace’s calls for socialism and crusades for social justice charmed John Stuart Mill – but annoyed the British establishment.

Most problematic for scientists like Darwin was Wallace’s belief that while this natural experimentation shaped the body – there was something divine about the mind, the soul. Such spiritualism was too loopy for rationalists. But Wallace integrated his radical politics, deep spirituality, bold ingenuity, and admirable nobility.

“It is curious how we hit on the same ideas,” Darwin remarked to Wallace in 1867. As On the Origins of Species soared, Darwin – who clearly couldn’t believe it – wrote Wallace: “Most persons would in your position have felt bitter envy and jealousy. How nobly free you seem to be of this common failing of mankind.”

Wallace lived long enough to be showered with honors, especially the Royal Society's Royal Medal in 1868 and the Darwin Medal in 1890. Today, the Wallacea biogeographical region is a group of Indonesia islands, and hundreds of plants and animals are named after him, especially, the gecko Cyrtodactylus wallacei and the freshwater stingray Potamotrygon wallacei. The BBC broadcaster and naturalist Sir David Attenborough insists “there is no more admirable character in the history of science.”

On November 7, 1913, when Wallace died at the age of 90, the New York Times branded him “the last of the giants” – including Charles Darwin – “whose daring investigations revolutionized and evolutionized the thought of the century.”

Amid all the homages, of course, opposition was fierce. And the opponents had a point. Evolution was subversive. Questioning creationism shook Westerners’ faith in God. It undermined the central assumption that things, identities, are solid. The resulting liquidity in our mass self-perception has spilled over into an unfortunate fluidity in morality too.

Alfred Russel Wallace was countercultural enough to want to shake society economically. But he was traditional enough to remain centered, humble, and grateful for whatever glory he did receive. It’s worth reverting back toward his quite evolved proportionality, tradition, and balance.

FOR MORE…

Alfred Russel Wallace, The Malay Archipelago, 1869.

Alfred Russel Wallace, My Life: A Record of Events and Opinion, 1905.

John van Wyhe, Dispelling the Darkness: Voyage in the Malay Archipelago and the Discovery of Evolution by Wallace and Darwin, 2013.

Ross Slotten, The Heretic in Darwin’s Court: The Life of Alfred Russel Wallace, 2004.