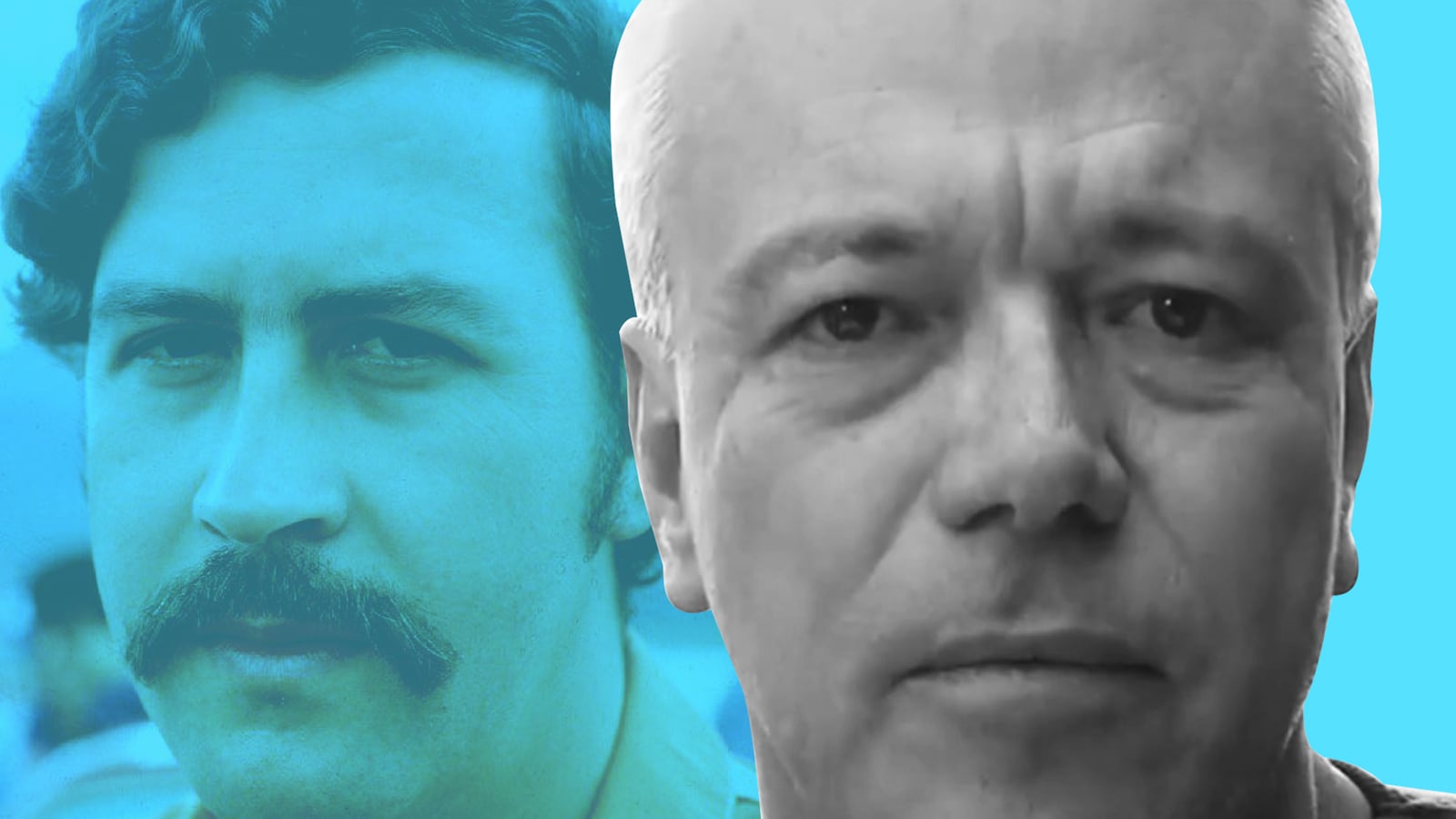

Tracking down the man who served as the top assassin of Pablo Escobar’s infamous Medellín Cartel sounds like an equal parts terrifying and hopeless task.

Terrifying because Jhon Jairo Velásquez “Popeye” Vásquez has confessed to killing about 300 people and ordering the deaths of some 3,000 more. Hopeless because, upon his release from Colombian prison last year, Vásquez announced plans to go into hiding. He believes he’s a marked man among his former comrades in the Medellín Cartel, past members of the inactive vigilante death squad Los Pepes, and La Oficina de Envigado, the cartel that inherited Escobar’s empire. At the time of his release, Vásquez pegged his own odds of being assassinated at 80 percent.

But it turns out that not even one of history’s most prolific hitmen can resist the allure of social media.

“Popeye” is on Facebook and he’s using his platform to spill dirt and seek redemption from the same public he terrorized all through the second half of the Medellín Cartel’s bloody reign. He’s confirmed his ownership of the page through videos and in Spanish-language media outlets.

At its peak, the Medellín Cartel supplied 80 percent of the worldwide cocaine market and generated at least $420 million in weekly revenue. The Cartel’s tactics are best summed up by Escobar’s concise business strategy: plata o plomo—silver or lead, which colloquially translates to “take this bribe or end up dead.” During the ’80s and early ’90s, Vásquez was the man Escobar would call on to dish out plomo for refusing plata.

Informants, businessmen, and rivals were all routine targets for Vásquez, but his greatest notoriety is owed to a string of attacks on high-profile members of the Colombian government. He kidnapped and tortured a future Colombian president and vice president, killed an attorney general, and helped plot the assassination of Colombian presidential candidate Luis Carlos Galán—the only murder out of thousands for which he was convicted.

The end of Vásquez’s run with the Medellín Cartel came in 1992, when he surrendered to authorities amid a string of assassinations carried out against the cartel by vigilantes, paramilitary groups, and the Colombian government itself. At the time, Vásquez told a reporter, “I don’t owe anything to anybody. I haven’t done anything wrong.”

However, in a series of jailhouse confessions prompted by attempts on his life by fellow inmates, Vásquez ultimately confessed to his 3,000-plus body count and, in doing so, provided information that helped secure the conviction of several Medellín Cartel members.

As for Vásquez himself, he was sentenced to a 30-year prison sentence and granted an early release in 2014 for good behavior after serving 22 years. His release came with a 52-month parole period during which he may not leave Colombia and must check in with authorities on a regular basis. Vásquez has taken the terms a step further by checking in with all of Colombia to inform them of his salvation.

Predictably, or perhaps not, “Popeye” now calls himself a man of God. His Facebook page makes him out to be much more complicated than that.

Dubbing himself “the historical memory of the Medellín Cartel”—Vásquez did not respond to requests for comment and all material from Vásquez’s Facebook page has been translated from Spanish—he doesn’t so much spread the gospel as answer the questions of a public that regards him with either cautious curiosity or outright disgust.

In response to a drawing of himself with the phrase “A real man isn’t the one who never fails, but the one who corrects his path,” one Facebook user pointedly asked, “And what about the people who couldn’t correct their path because they were assassinated?” The grim laconicism of a professional killer shines through in Vásquez’s response, “They died in the war.”

When asked what it feels like to murder someone, Vásquez simply replies “Buddy, the circumstances make the man.” Another user, betraying some morbid fascination with Vásquez’s past exploits, even went so far as to ask if the once fearsome “Popeye” had camped out on Facebook because he was too scared to resume his past profession.

It’s those questions, ones rooted in admiration for the Medellín Cartel’s ruthlessness, that reveal the retired hitman’s philosophical side: “Buddy, for better or worse, I’m the only survivor of the most tragic era of our history. I invite you to disarm your heart because I once lived with hatred like you do.”

As for those who believe he should still be in prison, Vásquez’s stock response is this: “Thanks for your opinion. It’s respectable.”

This is just a sampling of Vásquez’s Facebook interactions as his page has swelled to 28,000 likes in less than two months’ time—hardly surprising given the thirst for answers on the Medellín Cartel’s inner workings and Vásquez’s former status as a trusted member of Escobar’s inner circle. Really, it’s not like any society ever gets the chance to interrogate one of its most infamous members.

Vásquez’s Facebook page is, more than anything, an opportunity for himself and Colombia to experience something resembling a shared catharsis. However, it’s also become a vehicle for “Popeye” to rebrand himself as something other than Escobar’s favorite hitman.

Following the daring escape of Sinaloa Cartel kingpin Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman from Mexican prison in July, Univisión interviewed Vásquez to get his insight. He promptly snatched headlines by estimating Guzman’s escape cost the drug lord something around $50 million.

Whether Vásquez can become a fixture in Spanish language media remains a question that may be decided by just how willing the public is to accept the possibility that Vásquez is a changed man.

“Popeye” has convinced at least one person: Juan Manuel Galán, a Colombian senator and the son of Luis Carlos Galán. When Vásquez was released for his father’s murder, Galán said “He gave us the truth and asked for forgiveness. In my case, I forgive him.”