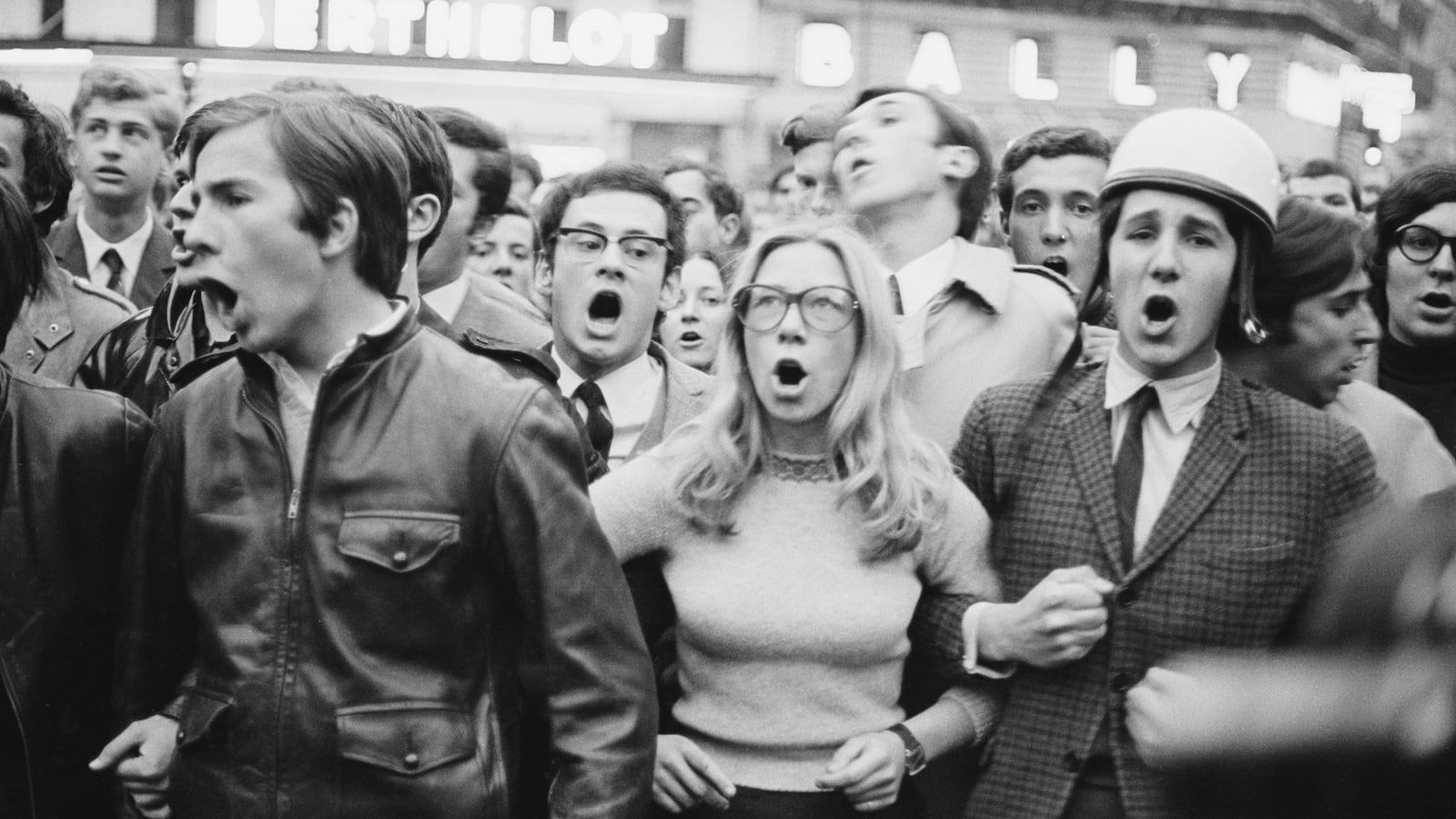

PARIS—Fifty years. Half a century since what’s been called France’s second Revolution: May ’68 when millions of angry students and workers filled the streets and brought the nation to a halt. And already the memories are beginning to fade once again.

For weeks this spring, you couldn’t go anywhere in France, watch any TV or listen to any radio without being transported back to la révolution du temps passé. Le Centre Pompidou, Le Musée des Beaux Arts, the Palais de Tokyo, the National Archives, La Bibliothèque Nationale, bookshops and private galleries everywhere. “The events of May ’68 remain anchored in France’s collective memory because they embody an optimistic moment of concrete utopia,” declared the director of the Beaux Arts, Éric de Chassey, a scion of France great noble families.

So it would seem as all the now creaky-kneed heroes of ’68 were carted out to celebrate the “revolutionary” memory. Several of those heroes, however, were having no part of it. Daniel Cohn-Bendit, one of the key “revolutionaries” spoke for half an hour one recent morning on France Inter, the country’s leading news station, about ’68. His message: Forget it! ’68 was never a real political revolt but rather a cultural scream against a top-down, stuffy cabal of old men who, bowing to church dogma, suppressed women, beat up gays, and treated France’s one-time Arab subjects like dirt.

Paris ’68 was not about power so much as it was about breathing. Drawing life in the fullness of each moment. In the United States there were the movements for civil rights, and for free speech at Berkeley, and against the Vietnam war. But in America “The Movement” was rooted in the resistance to death by lynching or the fear of death as your broken skull oozed out your brains into the jungle mud of Southeast Asia. Hell No, We Won’t Go was about surviving American insanity, while for French students and workers le mouvement was about throwing off the shackles of moribund cultural codes and opening the class-bound educational system to everyone—a streetwise cry to enact Jean-Paul Sartre’s call to live fully within each second of your existence. Vive Le Moment!

Or to recall one of the most memorable of ’68 slogans, also credited to Cohn-Bendit, “It is forbidden to forbid,” a direct reaction to the stuffy, quasi-Catholic moral dogma that dictated which hours boys and girls could visit each other’s dorm rooms. It was also a blunt rejection of a law that forbade divorcés from even entering the presidential palace. Even the sale of birth control pills then was barely legal.

That France, like prohibitionist Kentucky where I grew up, seems unimaginable today. But aside from lifestyle liberties, what has truly changed?

The French Communist Party, itself a kind of Stalinist labor hierarchy that had quietly crept into bed with the post-war rulers, is all but dead despite publishing a thin daily newspaper that still waxes nostalgic about that ’68 dream that shattered its authority.

For many years Cohn-Bendit, a longtime member of the European Parliament, has counseled his myopic dewey-eyed brethren to Forget 68, the title of his personal memoir. “Society today bears no relationship with that of the 1960’s,” he said at the 40-year anniversary. “When we called ourselves anti-authoritarian, we were fighting against a very different society.”

Cohn-Bendit, a moderate supporter of the current president, Emmanuel Macron, agrees with the critique of his former “Maoist” comrade, the late André Glucksmann: the 68 Revolution was not at all political. “Sixty-eight was simply a cultural rebellion and had no political impact.”

Indeed, very little has changed in the notoriously hierarchical French state. Bureaucratic “fonctionaires” remain docile before their superiors. Elected officials still hold multiple positions in regional and local governments simultaneously, politely lubricating legal graft. Most official holidays are still Catholic remembrances. State ministries regardless of party affiliation are largely run by graduates from a handful of “grandes ecoles” or selective universities—as they were a century ago. The president remains a five-year semi-monarch. Waiters and bartenders scrupulously follow the polite address, “Oui Monsieur, Oui Madame” even to customers they have known for decades.

Glucksmann, once told a New York Times reporter about his bafflement with the Call of ’68. He labeled it a memory cadaver “from which everyone wants to grab a piece.” In a country where nearly every local road boasts an historic monument and where grand chateaux have become so prohibitively expensive to maintain that their old family proprietors have off-loaded them to the public for parks and museums, a charming cult of memory pervades the atmosphere. (Unlike Greece and Italy where the past is largely in ruins, the French State’s commitment to these palaces is just another visual reminder of the power and importance of tradition.)

Or, as Glucksmann’s son, Raphael, who a few years back made a film with his father commemorating ’68, put it, “Young people are marching now to refuse all reforms, to defend the rights of their professors,” he said. “We see no alternatives. We’re a generation without bearings.”

That same odor of fear, panic and resistance to any change pervades France on this 50th anniversary stymied by a national rail strike. Just over a year ago French people elected Emmanuel Macron president on a clear promise to loosen up state institutions and regulations: cut the vast featherbedding that plagues most public services.

Target Number One was the unquestionably magnificent rail system which despite its excellent service keeps 15 and 20 percent of its 180,000 employees on the payroll with nothing much to do because the work they had been hired for has been outsourced. Firing public employees can cost more than keeping them on the payroll. The publicly owned train company has piled up more than $47 billion in debt, most of it accrued building the national network of high speed TGV trains. Those largely electronic trains deliver passengers from Paris to Bordeaux in two hours, from Paris to the Mediterranean coast in three hours. In exchange for picking up that massive debt, Macron has demanded several work rule changes, most importantly, ending the right of train operators to retire with full benefits at age 52.

No change, now or ever, the train workers’ union spat back—no matter that the early retirement age was based on rougher working conditions on the much slower trains that ran a century ago. Then, workers’ life expectancy was about 45. Now it’s 85. What that means financially is that the train drivers and conductors now collect retirement wages for about as many years as they’ve worked. It’s a formula for bankruptcy.

Students in 1968 made a persuasive argument that public universities should be opened to anyone who passed a lycée baccalaureate exam. Who could honestly oppose opening better education to all the people. In 1968 only 20 percent of lycée (or high school) students passed. Now 87 percent do and are guaranteed free access to universities. It sounds good—except that more than two-thirds of those university students drop out by the end of their second year, costing the education system billions for a promise that doesn’t work.

Student response this spring: shut it all down, change nothing. As Raphael Glucksmann put it, fear of finding no place in the robotized economy has left many if not most of today’s young afraid. Legitimately afraid—of never being able to move out of their parents’ homes to build their own lives in the current moment.

Were Jean-Paul Sartre, the most important guru of the ‘68 rebels (he marched with the students that spring) still alive, it’s hard to imagine what his response would be to the way that movement turned out. Several of ’68’s most cogent activists soon turned into neo-conservatives. Others like Cohn-Bendit simply counsel forgetting.

The pervasive posters, video-docs, street banners and public seminars are clear signs that millions here want to remember. But what do they want to remember? And how?

Sartre isn’t here to speak, but he did write at length about memory. Not misty nostalgia snapshots of a reality that never existed. Rather, Sartre argued that all memory is momentary: what we remember of 50 years ago—whether it’s about free education and sexual liberty or fighting a criminal war on a peasant population—is only what we remember individually and collectively in this morning’s or this afternoon’s fluid moments.

“I construct my memories with my present. I am lost, abandoned in the present. I try in vain to rejoin the past: I cannot escape,” Sartre wrote. “The real nature of the present revealed itself: it was what exists, all that was not present did not exist.”

Memory, which hardly exists in Donald Trump’s fake America, is critical to a civilized people, but in embracing memory, Sartre would surely have said: accept that the memory you had at 18 making love on the park bench bears only slight resemblance to the memory you forge today as you limp beneath the apple blossoms with your cane to that weathered bench.