More than just the title of Pat Barker’s new novel is reminiscent of Virginia Woolf’s 1922 novel Jacob’s Room. Woolf wrote her third novel in memory of her brother Thoby, who died at age 26 in 1906, and so too Barker’s novel is about a sister mourning the death of her brother. Elinor Brooke, Barker’s young protagonist, is a pacifist trying to separate herself from the war raging across the channel—an extremely stubborn position given the involvement of her beloved brother Toby, but one that Woolf herself maintained throughout the conflict. Though, as Barker reminds me, Woolf had nobody close to her whose life was on the line: “It might have been very different if Thoby was in the trenches.”

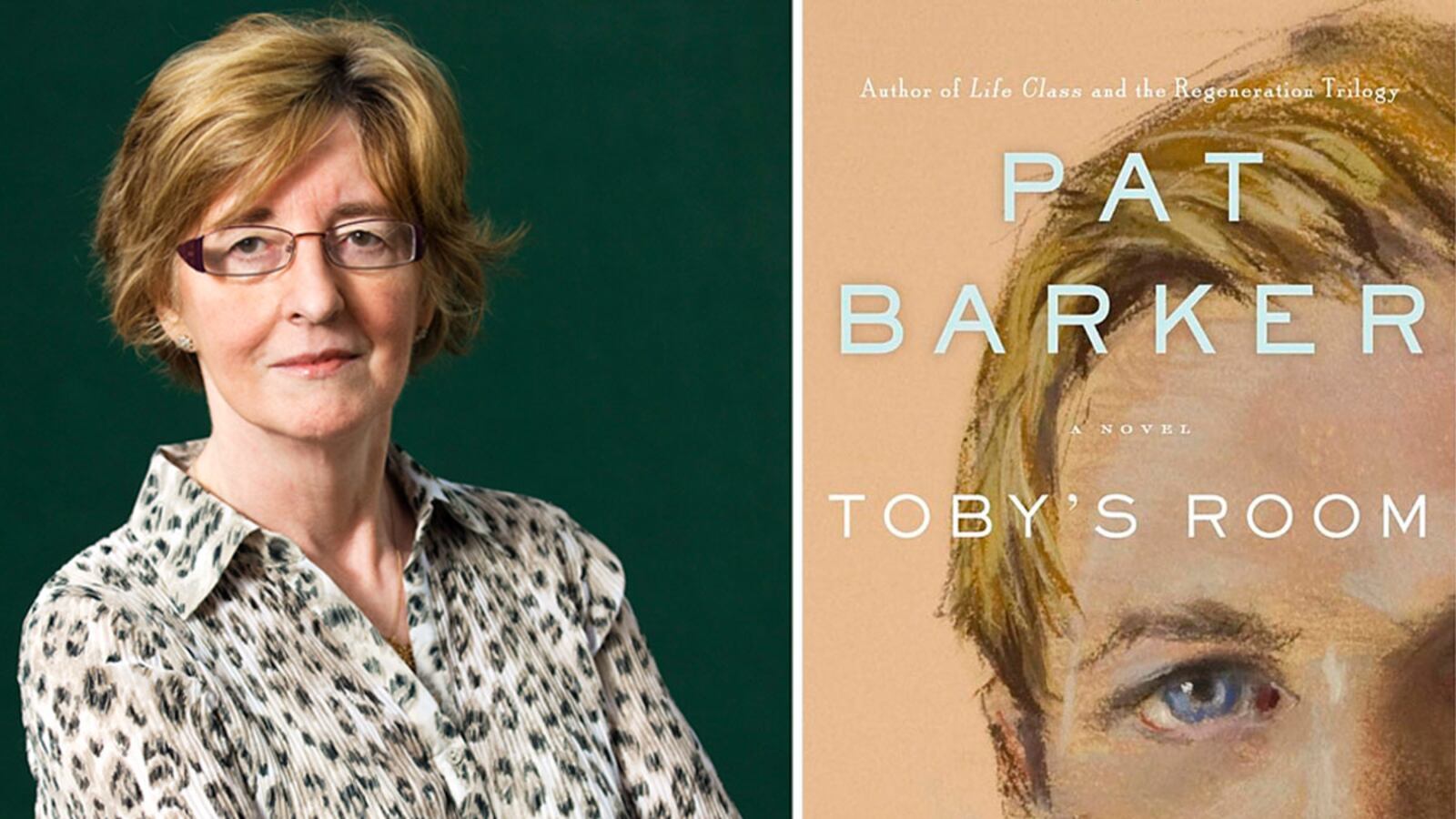

Barker made her name writing about the First World War in her Regeneration trilogy—Regeneration, The Eye in the Door, and The Ghost Road—published in the 1990s. Based on meticulous research, the novels fictionalized the real-life meeting between poets Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon in 1917 at Craiglockhart Hospital in Edinburgh, where they were both receiving treatment for shell shock under the care of the army psychiatrist W.H.R. Rivers. Alongside the rise of trauma theories in the 1980s, Barker’s novels brought the psychological realities of the First World War home to the reading public, making an indelible mark on the literary and historical landscape ever since, an achievement cemented by The Ghost Road ’s Booker Prize win in 1995.

Never one to shy away from the shock factor, Baker’s new novel, Toby’s Room, opens with an act of incest between the siblings that then hangs heavily over Elinor as she plants her “first spindly shoots of independence,” living alone in London as a bohemian student at the Slade School of Art. Despite his absence from the majority of the text, as a metaphor for male privilege Toby continues to take up room throughout the story—from before his birth in the womb, where he crushes his underdeveloped twin to death, to long after he’s reported missing in action. Elinor is unable to fully escape the suffocating presence of her brother, and after he’s killed, she becomes obsessed with uncovering the details of his death, a quest that eventually ends on the wards of Queen’s Hospital in Sidcup, where pioneering plastic surgeon Harold Gillies is treating disfigured soldiers returned from the front.

Running throughout the novel are questions about the relationship between art and conflict. Having attended anatomy classes in the dissecting room at the medical school before the war as part of her life-drawing training, Elinor’s contribution to the war effort is sketching the facial wounds of Gillies’s patients, under the supervision of her old tutor, the surgeon turned artist Henry Tonks. There is, Barker explains to me, a “natural marriage” between the work of the plastic surgeon and that of the artist, and Barker’s integration of the two is, indeed, nothing short of a masterpiece. Made ever more so, perhaps, by the uneasy undercurrent of Elinor’s realization that she’s able to respond aesthetically to wounds “that should have inspired nothing but pity.” A soldier with half his face blown away reminds her “of some of the ‘fragments’ they used to draw at the Slade where so often a chipped nose or broken lip seemed to give the face a poignancy that the undamaged original might have lacked,” his injuries throwing “the beauty of his remaining features into sharper relief.”

Whether art should be a response to war is a question Baker first posed in her previous novel, Life Class, published in 2007. This was where we first met Elinor and her fellow students Kit Neville and Paul Tarrant, two young men whose stories eventually become entwined with that of her brother Toby on the front line. Barker modeled her idealistic young characters on a group of real-life artists studying under Tonks before the war: Mark Gertler, Christopher Nevinson, Paul Nash, Stanley Spencer, and Dora Carrington. Elinor’s attempts to ignore the war are set against Neville’s hotheaded declaration that it’s a “painting opportunity” and Tarrant’s more considered argument that he feels impelled to paint exactly what he sees, horrors and all.

In an exchange between Tarrant and Elinor in Life Class, he tries to convince her that it isn’t right that all this suffering “should just be swept out of sight”—a sentiment that could well be applied to the way that Barker has applied herself to exposing the details of the First World War in all it’s mud-splattered, blood-soaked gore since she first turned to the subject.

“Culturally, the First World War is the war that stands in for other wars,” Barker says, explaining her decision to revisit the period. “I think the loss of life and the loss of innocence reverberates to this day—we still look to Wilfred Owen’s poems and Paul Nash’s landscapes.” As in the Regeneration trilogy, Toby’s Room marries fact and fiction in having real-life historical figures interacting with her fictionalized characters. Like Rivers before them, Gillies and Tonks have been pulled from the annals of history—and an online archive of photographs, portraits, and case histories of their real-life patients is readily available. She confesses that this is a process that “comes fairly naturally.” Her rules are simple: “Never make the historical character do or say something he would not have done or said.” It’s all a matter of being “fair to them and accurate about them.”

This truthful rendering of the historical figures is balanced, of course, by the revisionist aspect of her works—her exploration of wartime homosexuality in the Regeneration trilogy, and here in Toby’s Room the imbalance between the sexes as seen through what she admits is the “obvious” doubling of two siblings, setting female confinement against male freedom. Elinor’s somewhat unaccountable pacifism isn’t the only manifestation of her obstinacy, but this, Barker explains, was entirely deliberate. “She isn’t an entirely likable character,” she admits, “but for a woman of her generation to say that she wasn’t going to get married, that she was primarily a painter, required a level of obstinacy that we can hardly imagine these days.” Giving a voice to the traditionally disempowered is a common thread in Barker’s work, whether it’s women like Elinor, eager for their independence, or shellshocked soldiers who need encouragement to articulate their fears. This is an issue that will return in Barker’s next novel, which she’s working on now—the final volume in this second trilogy—when she turns her attention to another real-life historical figure, the Scottish medium Helen Duncan, who in 1944 was the last woman in Britain to be tried as a witch after revealing a supposed state secret during a wartime séance. “She was an uneducated woman who had enormous power for a brief period,” Barker explains, “but, as a mere conduit for the spirits to talk through, at the same time she was completely passive.”

We end our conversation chatting about the Man Booker shortlist, Barker commenting wryly that the Regeneration trilogy would have “sunk without trace” had it not been for her own win. One might well assume that her success marked something of her final word on the period, but this equally gripping and majestic return proves that there’s still more to say.