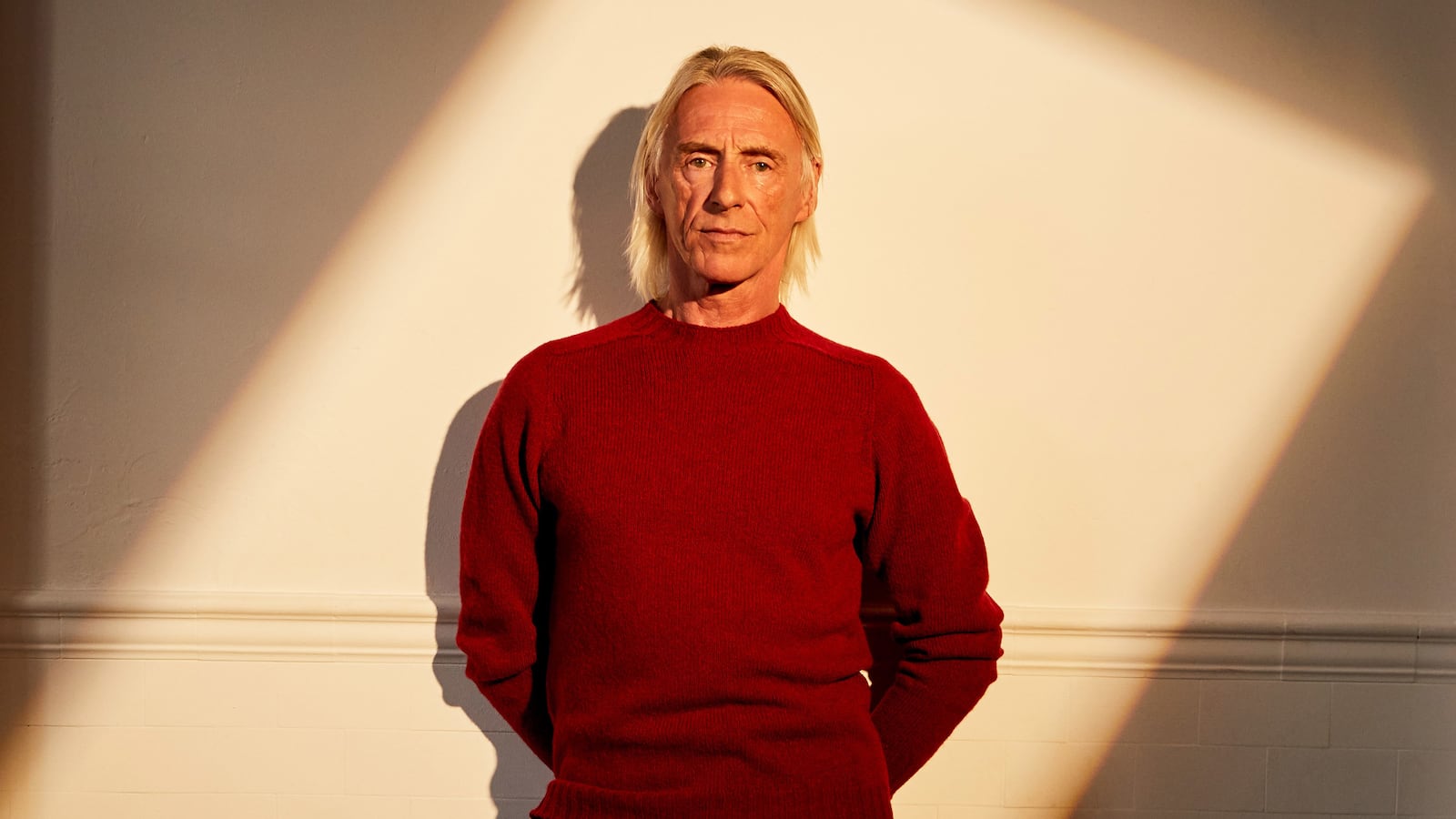

“There’s so much pain and hatred in the world right now,” Paul Weller, the U.K. musical icon tells me as we sit down to discuss On Sunset, his album due out July 3rd. “I wanted to create something joyful and upbeat, that could give people hope in this moment.”

And that’s precisely what On Sunset does. While it draws on everything from folk and psychedelia to freakbeat and musique concrète, at its core On Sunset is a soul album. Longtime influences like Marvin Gaye, Curtis Mayfield, Betty Davis, and Ann Peebles creep through, as do more obvious nods to Bobby Womack and Bill Withers, all filtered through Weller’s finely-honed, neo-mod sensibility.

And while it was recorded long before the coronavirus pandemic, or the killing of George Floyd, On Sunset still feels remarkably of this moment.

“I imagined everyone out in the streets, marching together in solidarity,” Weller says of the George Harrison-esque song “Walkin’.”

Still, he insists any connection to current events is purely coincidental.

“I wanted to make a record that was joyful, but not because of the lockdown or COVID-19, obviously,” he insists. “Because I wouldn’t, anyway.”

Paul Weller is a legend in his home country, as well as in Europe and the Far East. The man who broke up punk idols The Jam at the height of their fame in the early ‘80s, and then disbanded blue-eyed soul progenitors The Style Council at the dawn of the ‘90s, is now 15 albums and nearly thirty years into a solo career.

While his early solo albums—Wild Wood and Stanley Road, in particular—paved the way for Britpop, in the last twelve years Weller, who just turned 62, has found new inspiration in some of the most seemingly unlikely places.

“After I got the Brit Lifetime Achievement Award, and was offered the CBE (he turned it down, unceremoniously), I got to a point where I felt oddly free to do whatever the fuck I wanted,” he says.

In the wake of those awards, Weller released one remarkable album after another. 2008’s 22 Dreams was an ambitious epic, while Wake Up the Nation, Sonik Kicks, A Kind Revolution, Saturns Pattern, and True Meanings explored modern-day punk, Krautrock, classic singer-songwriter conventions, experimental electronica and elegiac, acoustic-based music, respectively. All were sonically adventurous, full of one left turn after another, leaving Weller alone amongst his peers from punk’s Class of ’77 as an artist who was still pushing boundaries while selling out tours and scoring hit records.

Weller insists it was all partly accidental, but that experience—not to mention an enviable work ethic—accounts for his late-career rebirth.

“When I’m writing, there’s a theme, and a subject to the song I’m working on, but there’ll also be some other little abstract things that come in, just because that’s what I think of at the time,” he says of his embrace of the digital recording process, and its cut-and-paste nature. “I think the quality of the recordings has got so much better over the last few years, to the point where I personally have trouble hearing what’s analog and what’s digital. And also, the editing thing is just mental, man. You can chop your song up and tie a bridge around back to front, or put a chorus in front of the verse. And whereas there was a time when I would’ve edited the weird bits out, these days I’m more inclined to keep them in. So there ends up being abstract elements in the songs that makes them interesting, I think.”

And, of course, the sonic through line is Weller’s love for old-school soul.

“The soul albums I loved when I was young weren’t always political,” Weller says. “And even when they were, they were about good tunes and good melodies that took you to a really special place. So I wanted to keep this album quite soulful, with a kind of electronic edge to it as well, so that it would be like those albums in that it was a little journey.”

There’s perhaps no better example of Weller’s soul-drenched pop than “More,” a standout track off On Sunset—pushed along by an arresting string arrangement by Game Of Thrones composer Hannah Peel, who also contributed to True Meanings and last year’s Other Aspects live album. The song grew from Weller taking a hard look at all he’s accrued for himself and his family over the years.

“I look at my family, and I’m grateful for all the money and privilege we’ve got, but materialism doesn’t really make you happy,” he explains. “It’s always more, more, more: The latest iPhone, or whatever, marketed to us as though we need it, when people are struggling to pay the rent or put food on their plates. We all need to take a really hard look at that as often as we can, I think, and I’m glad that at least some of us finally are.”

Weller entered the musical—and political—fray 43 years ago this spring with the electrifying first single by The Jam, “In The City.” Over the years he’s dabbled in political songs—and even toured in the ‘80s with musician/activist Billy Bragg—but now he feels it was the naïveté of youth that drove him, and was mostly futile.

“I find myself saying the same things I’ve said, or that I have been saying, for the last 30 years, and that feels pointless,” he says. “I don’t mean that people speaking out is pointless—because what we’re seeing right now in reaction to our governments’ incompetence and greed, especially from young people, is fantastic—but for me to say the same things in songs that I was saying in 1979 bores me. Besides, I write songs for people. I’m not writing songs for politicians or those sorts. I’m trying to connect more with people on a different level anyway. I’ve no agenda, politically, anyway, and I’m not of any part of them at all, or any party.”

Once the topic is raised, however, Weller is more than happy to continue.

“I would like to think people would get something from my songs, whatever period we’re talking about,” he continues. “What people take away personally from a song that they like can be many, many different things. Some people love songs and they don’t even really know the words to them. Or if they’ve sung them a thousand times, they’ve never stopped and thought about them. So there’s what I intend in a song, but what people take from it, which I have no control over. But I do find it a little bit rich from someone like fucking David Cameron saying how ‘Eton Rifles’ was his favorite song. That’s a bit like, ‘Fucking come on. The clue’s in the fucking title.’”

And so Weller is also adamant that he’s right in his choice to steer clear of politics.

“This is what I want to put out at this point in time, not that one musician from England is going to make a scrap of difference to the wider world,” he says. “I know that. But if it makes someone happy and inspired and feel good about themselves and their life, then that’s what I need to do.”

Paul Weller performs at Glastonbury

Ian Gavan/GettyWeller—who famously left behind the safety of both The Jam and The Style Council—also no longer bristles at the inevitable questions about the reunion/legacy circuit he refuses to be a party to.

“I understand that there’s people that have got sentimental connections to some tunes, because they represent a certain time in their life,” he explains. “And I get that. But to be fair, we tuck a few oldies in. It’s just that my set’s not full of them. But don’t forget that I’ve been doing the solo thing for fucking decades. Something off Wild Wood, that’s from the last century!”

Meanwhile, with no touring in his immediate future, and with the studio he owns at his disposal, Weller is threatening to release another album as soon as next year.

“I’ve been writing loads, because of this lockdown,” he says. “I’ve not been writing lockdown, obviously, or coronavirus. I’ve avoided those subjects. And now I’m like, ‘Well, I want to fucking play these now!’ And the new album isn’t out yet! So we’ve been recording—sending parts back and forth between the band—and they’re really good pop songs, man. And I use that term very broadly. Because they’ve all kind of got some funky things in them. So I’m going to call it ‘fat pop.’”