In a new and occasional series, Rewind will look back at a television show or film that has proven to resonate.

I, Claudius celebrates the 35th anniversary of its U.S. broadcast this year. A rapt and devoted audience consumed this spellbinding ancient-Rome period drama when it first aired in 1976 on the BBC in the U.K., and in 1977 on PBS’ Masterpiece Theatre. Starring Derek Jacobi as the titular character and featuring some of the best boldface names in British acting circles, the Emmy Award–winning show—which ran 12 episodes and is today being released as a remastered five-disc DVD box set—is a multigenerational saga about the emperors of ancient Rome and the conspiracies, intrigues, murders, and madness that stood in their shadows.

Despite the fact that the poison-and-plots-laden miniseries, adapted by Jack Pulman (who wrote every episode), is now approaching middle-age, I, Claudius—based on the 1934 novel (and its sequel) by Robert Graves—remains one of the best dramas ever to air on television, a deft masterpiece of story, character, and, perhaps most importantly, vivid atmosphere. Shot on multiple cameras (whereas today it would be shot on a single camera in a more cinematic fashion) and with a budget that didn’t include throngs of rioting plebs, the style lends an overtly theatrical and intimate air to I, Claudius, as though the television set itself were the proscenium of a great theater. It’s here that the court intrigues of several emperors—from Augustus to Caligula—play out episodically; the show itself takes place between the years 24 B.C. and 54 A.D., charting the ups and downs of the Julio-Claudian imperial dynasty as characters breeze in and out of the frame, returning decades later to enact bitter revenges or suffer themselves from the hands of poisoners, assassins, or godly whims.

Narrated by Jacobi’s Claudius, a stuttering, limping man thought by all to be a fool who is nonetheless prophesied to one day rule Rome, I, Claudius dramatizes the period leading up to his birth and through his death, as he—now an old man and fading from this world—writes down the story of his life and that of his conniving family. The show’s opening sequence—which depicts a snake, a venomous adder, slithering over a mosaic tile floor—is both iconic and only too fitting, given the series’ depiction of ancient Rome as a nest of vipers, the most deadly of which is Livia (Siân Phillips), wife of Augustus and grandmother of Claudius.

Phillips’s performance is staggering, and instantly renders Livia as unforgettable: a manipulative and wicked conspirator who is only too willing to murder even her own offspring for a taste of true power. Capable of dispatching her victims via poison or a vicious bon mot (she gives Dame Maggie Smith’s Dowager Countess on Downton Abbey some stiff competition in that department), Livia is the very definition of cunning, a ruthless and unstoppable force greedily amassing influence, an amoral snake whose venom kills nearly everyone she with whom comes in contact. Phillips imbues Livia with a raw vitality and glittering malice that echoes more than three decades after the performance, one that intensifies as Livia grows older and more dangerous.

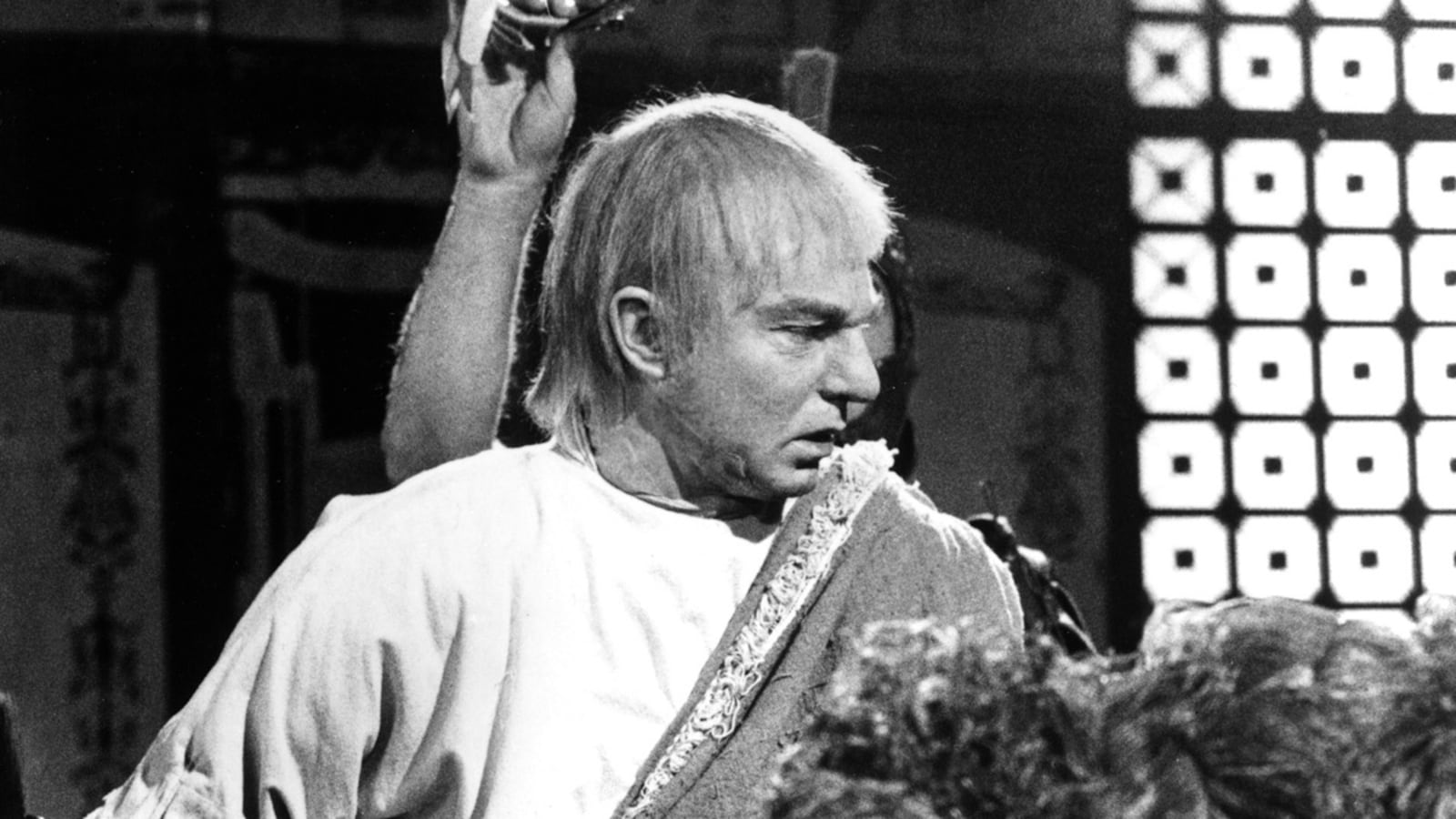

But Phillips isn’t the only one who transfixes the audience. Brian Blessed, in a relatively “quiet” performance (if you’ve ever seen Blessed elsewhere, you know what I mean), is a fitting Augustus. Patrick Stewart—looking rather like a young Richard Gere here—plays upstart conspirator Sejanus; John Hurt is distressingly perfect as the mad emperor Caligula, given to orgies, incest, patricide, and delusions of grandeur. (In one of the more troubling sequences of the series, Caligula—having proclaimed himself “reborn” as a god—cuts open the stomach of his sister, who is carrying their incestuous child, and eats it, believing a new child would spring from his head, a là Athena.) John Rhys-Davies is suitably oily as Caligula’s regicidal general Macro, while George Baker shines as the perverse Emperor Tiberius, and even comedy actor Christopher Biggins appears late in the series as Nero. (Truly, this was one production that boasted an insanely large—and influential—cast.)

At the heart of the show, Jacobi is stellar as Claudius, who learns to play up his physical failings to mask his own intelligence. Buoyed by forces that he cannot control, he is destined to become emperor, even as he desires to escape the fate of so many others around him. Ironically, his own follies lead to his destruction. Throughout the series, fate has a way of intervening: after narrowly escaping death on several occasions at the hands of various family members, Claudius ascends to the rank of emperor … only to learn that no one, not even he, is truly safe from the pervasive rot of corruption and greed.

It proves, perhaps, that the more things change, the more they stay the same.

One doesn’t need a Sibylline prophecy or an augur to see just how potent and powerful I, Claudius continues to be. The success of I, Claudius, both in terms of critical acclaim and commercial triumph, continues to spawn successors. HBO’s short-lived Rome (which overlapped somewhat, towards the end, with some of I, Claudius’ plot), Starz’s blood-spurting Spartacus, and Showtime’s The Borgias all owe a huge debt to this remarkable production; revolving around actual historical events, both shows—laden with graphic sex and violence—are clear descendants of I, Claudius’ vast legacy. (What seems positively tame nowadays must have felt groundbreaking in the 1970s. Before the advent of premium cable channels, PBS was the only place to see content that broke beyond the puritanical on television.)

Likewise, there are clear parallels between I, Claudius and The Sopranos, whose protagonists both embody the struggle between blood relations and blood debts, as they are forced into roles of leadership seated on thrones metaphorically built from the bodies of their predecessors. And like Claudius, Tony Soprano must deal with a Machiavellian maternal figure in the calculating and deadly Livia, whose age belies a cunning and twisted heart.

While Sopranos creator David Chase has stated that Livia Soprano was inspired by his own mother (who died, perhaps fortunately or unfortunately, before The Sopranos began), there is a whiff of familiarity about his Livia, as though the ghost of Phillips’s ancient Roman empress had echoed through millennia to rain chaos upon yet another dynastic clan. If I, Claudius teaches us one thing, it’s that bad deeds not only go unpunished, but they can also echo for an eternity.