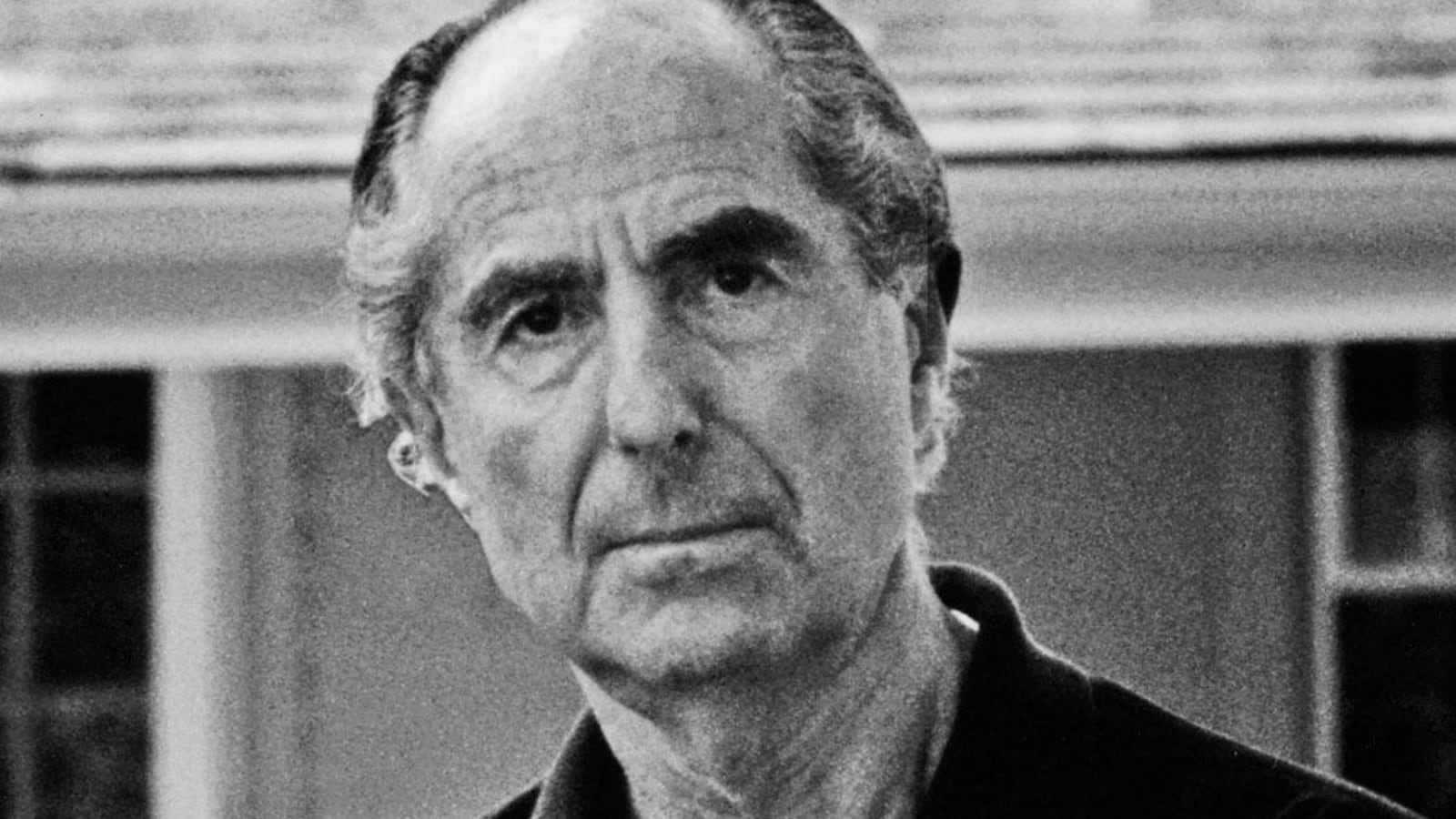

Tina Brown: The last 12 years, we’ve seen the most incredible creative surge from you— American Pastoral, Plot Against America, The Human Stain. And now you’ve written your 30th novel, The Humbling. Why such an incredible creative surge do you think just lately?

Philip Roth: I don’t know. I don’t know. I do the same things I always did. I work just as much as I always worked. And I can’t explain the fact that there have been a series of books coming rather regularly out of me. I work most days and if you work most days and you get at least a page done a day, then at the end of the year you have 365. So the pages accumulate and then I publish the books.

Tina Brown: I think that your writing is probably at its best now because it seems almost more direct, more simple. It has an urgency—particularly these short novels that you’ve been doing where you can sort of read them in a sitting and it feels like you’re taken over in one mood and that it’s almost written in one bite, which I’m sure it isn’t. How much rewriting do you do with these short books?

Philip Roth: I do the same kind of rewriting that I do in the shorts that I do in long books—and that is a lot. The book really comes to life in the rewriting. The first draft is extremely crude, but at least it’s down. So when I have a first draft, I have a floor under my feet that I can walk on. And then, especially with the help of the computer, rewriting is so easy to do with the computer, much easier than it used to be with the typewriter. So the books go through numerous drafts.

Tina Brown: So you don’t keep on writing one paragraph? You sort of do what I used to call a vomit draft, where you kind of just throw it all on the page and then go back and do the whole thing.

Philip Roth: Yes. That’s a good phrase—vomit draft. I do a vomit draft. And I may do several more vomit drafts. But eventually the writing takes time. What I want to do is get the story down and I want to know what happens as I write my way into the knowledge of the story.

Tina Brown: Do you usually start with a thematic idea or do you start with a character or a situation?

Philip Roth: Well, I’ll give you an example from The Humbling. I began with a line, which is the first line of the book: “He lost his magic.” I was thinking of an actor—not a particular actor, but an actor, who couldn’t act. The idea just intrigued me.

Tina Brown: Somebody you knew or somebody that you read of?

Philip Roth: No somebody that I’d heard about. Yeah. And I didn’t know much about him, but I liked the idea that he went on stage and suddenly it’s all deserted you and that you’ve lost your power. So the situation was very promising. And the first line was “He lost his magic” and so I wrote from that first line onward for me to find what happened.

Tina Brown: So performance anxiety must afflict writers as well as actors. I mean, have you ever felt that situation yourself that you wonder you might—I was going to say sit down, but you write standing up, don’t you?—that you might stand there at your lectern and you’ve lost your magic. Has that ever occurred to you?

Philip Roth: Yes, yes. It happens routinely between books. I think I write or publish as much as I do because I can bear being without a book to work on. But routinely when I finish a book, I think, “What will I do? Where will I get an idea?” And a kind of low-level panic sets in. And then eventually something happens. I don’t know. If I knew how it happened I would repeat the process, but I don’t know—something just occurs to me.

Tina Brown: In The Humbling, the character, Simon Axler, the actor, he embarks on this very self-destructive affair with this very threatening, sort of predatory girl. She’s a fascinating character. I mean, tell me about the genesis of this character, of this woman, who is predatory lesbian, actually?

Philip Roth: Is she predatory?

Tina Brown: She feels it to me. She’s so sinister.

Philip Roth: Mmm. Well, you’re a reader. The book has only had a very small handful of readers so far and nobody has said that about her before. I didn’t mean for her to be predatory. I meant for the situation to be unreliable. That is, he was embarking on an unreliable situation. I don’t think she’s any more predatory than everybody is. But she’s watching out for herself. She has a certain charm. A certain sexual charm, erotic charm. She makes him happy. So before we call her predatory, we must remember that for a while there, he’s extremely happy—this guy who’s miserable when the book begins and she destroys his misery. And then when she leaves him, she dumps him back into his misery, but I’ll remember that you called her predatory.

Tina Brown: At what point did you feel, or perhaps it was always in your mind, that she would be gay? She didn’t have to be gay to be unreliable.

Philip Roth: That was from the beginning. I thought that that was an unusual situation. I wanted to think about it. I didn’t remember anybody writing about it. There must be a book which has the situation in it—do you know about any?

Tina Brown: No. It was very striking.

Philip Roth: Yeah so there’s a heterosexual man—strongly heterosexual. And there’s this young woman, she’s forty—that’s young. And she comes to him directly from a long love affair—she’d been with this woman, I think, six or seven years. And her woman lover decides to become a man, if you recall. And she leaves her and then she comes upon Simon Axler who she knows because her family knew him when they were all young actors in New York.

Tina Brown: It’s a very striking moment in the book when she straps on that dildo- a green dildo. Tell me about writing those scenes. I mean, is it a hard thing to write a sex scene with a woman in a green dildo?

Philip Roth: No. I mean, no harder than writing a sex scene with a woman without a green dildo really. Most of my sex scenes have been with women without green dildos. This is a first for me, too, you know? It was actually interesting imagining it—imagining what would happen, how he would respond to it, what she would do with it, and what the byplay between them would be. So for me, it was fresh.

Tina Brown: Are sex scenes harder to write than other scenes or not—just the same?

Philip Roth: Well, you don’t want to repeat yourself for one. You don’t want to fall into the clichés for another. And you don’t want to be licentious really. You want to be descriptive, if you can be. And you’re not setting out to arouse anybody. A friend of mine read the book and told me that he was tremendously aroused by those scenes so I don’t want to tell you what I think about him, but I didn’t intend for that to be said.

Tina Brown: You said in an interview that you don’t think novels are going to be read 25 years from now. Were you being provocative or do you believe that to be true?

Philip Roth: I was being optimistic about 25 years really. No, I think it’s going to be cultic. I think always people will be reading them, but it’ll be a small group of people—maybe more people than now read Latin poetry, but somewhere in that range.

Tina Brown: Is there anything you think that novelists can do about that or do you think that it’s just that the narrative form is going to die out? It’s just the length of them or what? Is that what’s dictating you writing shorter books now?

Philip Roth: It’s the print. That’s the problem. It’s the book. It’s the object itself. To read a novel requires a certain kind of concentration, focus, devotion to the reading. If you read a novel in more than two weeks, you don’t read the novel really. So I think that that kind of concentration, and focus, and attentiveness, is hard to come by. It’s hard to find huge numbers of people, or large numbers of people or significant numbers of people who have those qualities.

Tina Brown: Do you feel that the Kindle is not going to be that? I mean, when I’m on airplanes now, I now see people with Kindles all the time. And a lot of people I speak have Kindles—you know, I have one, but I don’t read it as often because I still like books—tell me they read more on Kindle than they did on hard copy.

Philip Roth: Maybe. I’m not familiar with the Kindle. I mean, I’ve seen one but I haven’t used it. I read the piece in the New Yorker, by Nicholson Baker, which was very good. He had his skepticism. I don’t think the Kindle will make any difference to what I’m talking about, which is that the book can’t compete with the screen. It couldn’t compete beginning with the movie screen. It couldn’t compete with the television screen and it can’t compete with the computer screen I don’t think. And now we have all those screens so against all those screens I think the book can’t measure up. I may be wrong.

Tina Brown: In Sabbath’s Theater you said that “some shot just undoes them around 60. The plates shift and the Earth starts shaking and all the pictures fall off the wall.”

Philip Roth: I said that?

Tina Brown: Yes, you did.

Philip Roth: In the book?

Tina: Yes, apparently. Yes you did. And this quote here. Perhaps you don’t recognize your own books after you’ve written so many—30 books.

Philip Roth: Not anymore.

Tina Brown: Well, now you’re in your 70s. I mean, what difference are you perceiving in yourself? If you’ve been through the plate shaking 60s, what’s the 70s like?

Philip Roth: Mmm. They’re great. They’re great. I can’t wait for more of them. And then I’m just looking forward enormously to the 80s. They can’t come soon enough for me. It’s odd because you don’t associate the number with anything other than a house. 76. I’m 76. That’s a house number. That’s not an age. And it’s hard to adjust to this fact. The hard part is, of course, the proximity of death. The number has no meaning as long as you’re fit and healthy. But you know that you only have so much time left and you don’t know how much it is. It could be a very short time. And that’s a bit of a wake up call.

Tina Brown: How much do you brood about that?

Philip Roth: I wouldn’t say daily, but I think weekly would be a true answer.

Tina Brown: And as a writer, are you thinking about that, “I want to write X more books? I’ve got this much to say?” Or is it just that you’re keeping going with the creative ideas; it doesn’t come into the equation?

Philip Roth: I don’t care about X more books. I care about being occupied in writing about. So I want my time to be occupied with writing. I rarely, if ever, had another book in mind while I was writing the previous book. Each book starts from ashes really. So no, I don’t feel that I have this to say or that to say or this story to tell or that story to tell, but I want to be occupied with the writing process while I’m living.

Tina Brown: Your kind of second surge as it were of creativity came after you’d been away in London for about 12 years. I mean, did that exile in London jolt something in you when came back, do you think?

Philip Roth: Yes. I do. That’s exactly what happened. I was living in London from 1977, I think to 1989 for about seven months a year. And when I left London, I came back and lived in my house in northwestern Connecticut, which is out of the American world, really so I had very little America during those years I was away. And when I came back, I was thirsting for America. And what I discovered was that I had a new subject, which was an old subject. And that’s when I began to write American Pastoral, I Married A Communist, The Human Stain—all those books that have a strong American background. So I rediscovered my own country really. It was a blessing. I don’t think I would have ever come at it that way had I not been away all that time.

Tina Brown: And now you’ve been back for another sort of 12 years. I mean, how do you feel about America now. I mean, you’ve lived back here now for 12 years. Are you as enthralled by it? Do you feel that the Bush era has changed America? How are you feeling about the state of America right now?

Philip Roth: Well, I was here through the Clinton years and the Bush years, wasn’t I? I came back in ’89. Do you have to answer that question?

Tina Brown: You can try. You can avoid it?

Philip Roth: You know, I’m an Obama supporter. And if you’re an Obama supporter that means you had a hard time during the Bush years.

Tina Brown: Yeah. And how are you feeling he’s doing now as President?

Philip Roth: I think he’s doing the best he can.

Tina Brown: What do you think of him as a writer?

Philip Roth: That’s a good book. Dreams of My Father, is that what it’s called? I read it with great interest, in part because it’d been written by this guy who was running for president, but I found it well done and very persuasive and memorable too.

Tina Brown: It’s actually 40 years since you wrote Portnoy’s Complaint. Have you managed to shed what you once called, “a reputation as a crazed penis?”

Philip Roth: I don’t know. You tell me. What are people saying?

Tina Brown: I mean, in some ways, you sort of went into retreat from that celebrity. Do regard that period as sort of a set back or as a necessity for you as a writer?

Philip Roth: I lived through it. It was only my fourth book. As you mentioned, this is my 30th book so that was 26 books ago. It did determine the perception of me for a long time as a writer. And I think it colored the reception to some other books. I think if you sort of extract Portnoy’s Complaint from my work, I would be read a little differently. But Portnoy’s complaint was a big marker. I don’t regrets about writing it or publishing it. I couldn’t have predicted what happened, which is that it became a huge, notorious success. But I think people who took exception to it at the time are mostly dead.

Tina Brown: Is that gratification?

Philip Roth: Yes. And it also is much less inflammatory to younger generations.

Tina Brown: Have you read Portnoy recently? I mean, 40 years later, how does it feel reading it now?

Philip Roth: Oh. I wouldn’t dream of doing it. Have you read it recently?

Tina Brown: I haven’t, but I think I might leave this table and go right off and do so.

Philip Roth: Okay. No, I don’t know that I could read it, really. It’s a youthful indiscretion.

Tina Brown: Of course with Portnoy’s Complaint 40 years ago, I mean, you were the ultimate young turk of literature. Now, here you are, absolutely the most celebrated American writer and the greatest American writer, everyone now acknowledges that. How does that feel having gone through that arc now?

Philip Roth: Well, I didn’t particularly respond well to being a young turk so I think I prefer this to that. Yes, it’s good. It’s nice.

Tina Brown: And what do you feel you’re wanting to write in the next 10 years? Are you hoping to do another hot streak like the one you just had?

Philip Roth: What I would really love to happen to me would be if I came upon an idea that would keep me busy until I die so I wouldn’t have to go through the business of thinking up a new book. But I wouldn’t mind writing a long book which is going to occupy me for the rest of my life.

Tina Brown: Philip Roth, thank you very much.

Click here to watch the video interview.