“Friendship! And Equilibrium,” Philippe Petit says. He lifted a glass of Prosecco.

“Friendship. And Equilibrium!” he repeats.

The E-word hovers, as if capitalized.

We are a small group on the porch of the East Hampton house of James Signorelli, the Saturday Night Live producer, who Petit calls his best friend in America. They first met a couple of months after his 1974 World Trade Center walk.

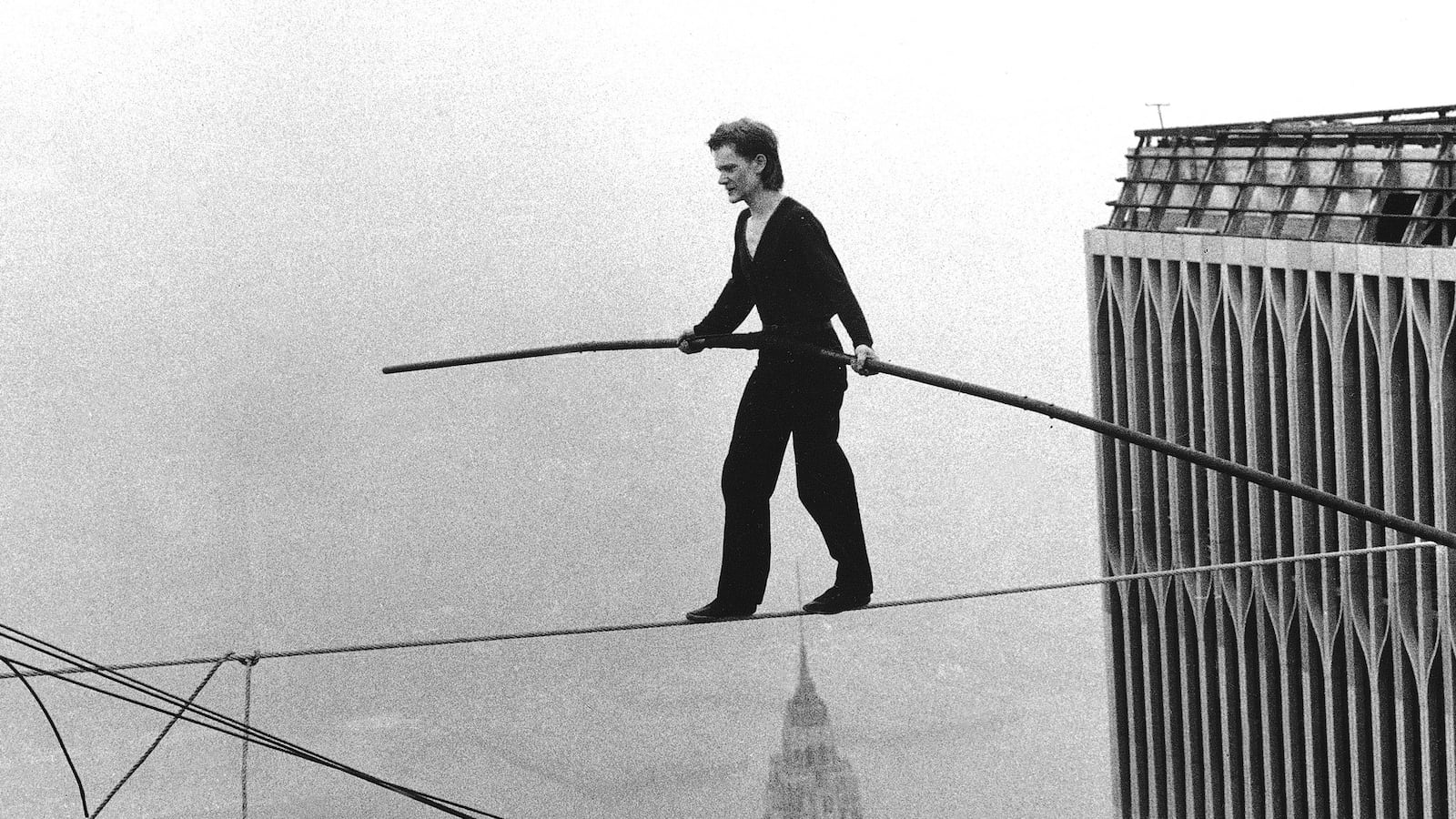

It is 40 years since Philippe Petit made a wholly illegal walk 1,350 feet above the ground between the two towers of the World Trade Center, going back and forth eight times. It was a week before his 25th birthday. He had been dreaming of making this walk since he had read about plans to construct the towers when he was 17. He had made illegal walks before, but this one made him world famous.

“I was assailed by people,” Petit says. “Everybody wanted me to be rich and famous on my art. And I said no to all the commercials and all the seedy offers.

“But Jim said, ‘Let’s do a feature film about your walk.’ And he took all the old footage I had shot. And we started writing the story. And then we became friends. And now we are guests in his house for the anniversary. I like it when you complete the circle.”

Petit usually marinates his projects, sometimes for many years. “I did a walk in 1973 illegally in the northern side of the Sydney Harbor Bridge,” he says. “And that day there was a picture taken of me on the top of the Harbor. And I was pointing at the Opera House, which was still under construction. And I thought I should come back one day to do a giant walk over the Sydney Cove from the Opera House to the top of the bridge. And that project, a little bit like Christo, went on for 14 years and then it kind of died.” Now the project is alive again 41 years later.

His original 1974 WTC walk happened in much the same way. “I study [sic] the Towers in France when they were being planned,” Petit says. “Then I saw them being born, and I followed them growing up. And I married them with a smile of my own.”

This anniversary walk had a different trajectory. “The past two years was so busy for me. I wrote two books. And I have so many other projects. Every year I am conscious of the anniversary of my 1974 World Trade Center walk. But you know a 17-years anniversary is not very interesting. Twenty years ... or 30 years ... But when 40 years was coming I thought, well, 40 years is a nice round number. Let’s do it as a celebration!”

Petit, who defines himself as an “Art Criminal,” kind of like a Street artist but with a higher level of physical risk, had wanted to make it an illegal walk. Not! “You know trying to do this in New York City would be impossible right now,” Kathy O’Donnell, Petit’s partner and manager for almost three decades, says. If he were to do something illegally he would be shot these days. “It wouldn’t be like then. Let’s wait for the guy for 45 minutes to come in off his wire. It would be bye-bye!” Doing a legal public walk was a no-no, too. “Anything over 20 feet you have to have a safety belt. Or a bubble underneath. You know, an airbed.”

A private walk was the way to go. A close friend, Ted Hartley, proposed the LongHouse Reserve in East Hampton as the venue. Petit and O’Donnell liked the location, a nonprofit sculpture garden on the fringe of East Hampton’s North West woods, right away. They scouted a few other options but the LongHouse Reserve was the one.

As a venue, the Reserve is, of course, quite a remove from the original. The walk, for one thing, will be just 25 feet above a pond. But that does not, so far as Philippe Petit is concerned, make it a cakewalk. “I have a fear of water, believe it or not,” he says. “To put a wire 12 feet over a swimming pool frightens me. I don’t like water. And that’s one of the little difficulties of that walk. But I can be thousands of feet high above concrete, it doesn’t bother me. To be 20 feet high above water...water is not my element.

It was on the original WTC walk that Petit had one of his more unpleasant moments on the wire.

“The wire was one of the worst wires,” he says. “I had all kind of problems with the rigging the night before. So, yes, I had one of those...I would not call them moments of doubt. But I would say the appearance of a question mark. But I am very good at turning a question mark into an exclamation point. I will shape the curve! Because basically I will never set myself on a wire and do that first step if I am not sure that my last step will be successful.

“One thing that people really do not understand is...‘He risks his life!’ I am the opposite of that. I will never risk my life…Sometimes, yes, there are moments but usually it’s a quarter of a second, it’s not a minute. Maybe I had a little absence of focus for a quarter of a second. Or maybe something happened. A thought came into my brain, and I didn’t repel it instantly on the wire.”

What kind of a thought?

“My focus on the wire is the result of a lifetime of training. And at the beginning I decided to put on blinders. Because the only thing important is the wire. That was a mistake. That focus is dangerous. Because when you are on the wire, the universe that is around can be aggressive and actually deadly. So then I started creating a focus which now I would describe as: I only focus on the wire while I completely listen to my surroundings.

Petit says that somebody once told him they understood his reliance on his eyesight, his sense of touch, even his sense of smell. But his sense of taste? What was there to taste up there?

“I said ‘Aha! You are mistaken.’ I actually sometimes ...if you look at a video of me walking sometimes I do this weird…”

He mimes an open-mouthed chew.

“I open my mouth wide! To what? To breathe more oxygen? Maybe. But to chew! To feel–is there humidity in the air? Oh, yes! There’s thunder maybe coming. And one day, taste saved my life because I was in the middle of a big crossing. There were grey clouds. But my eyes could see the grey become black clouds, which was not good. I could taste on my tongue and smell too and I thought, shit! A biblical rain is going to fall. I have to get my arse on the other side. It was about a hundred yards and I went quite fast. And the second I arrived and did my last step, there was thunder and rain pouring. If I had been a hundred yards away on the wire I would not be here to tell the story.”

It happened that I interviewed Philippe Petit not long after his WTC walk for Vanity Fair. We ate a meal in Windows on the World, the restaurant on the 106th and 107th floors of the World Trade Center. Impossibly, even through thick glass, I felt a twinge of vertigo. This memory prompts an inevitable question: “We live in an increasingly scary world,” I say. How does Petit feel about 9/11 now?

“Well, I don’t have television,” Petit says. “And I don’t really read the papers, which is ridiculous I’m sure. Basically I am an alien. I live in the clouds for my art. I do not understand anything in politics. I am a street juggler. I have an illegal existence. I have to get a permit, I have to get permission. That’s not me, I go with my unicycle and I juggle anywhere. To me the world of politics is like rain. If it’s raining, well, face the rain or steal an umbrella. But don’t try to fight the rain. So I do not comprehend and cannot talk about politics.”

My question was not about politics, I said. It was about 9/11 and the future.

“Aha! Well, I am a very optimistic pessimist. I just think of human beings, they are slaves to their little machines, they put things in their ears, they put things in front of their eyes, they don’t smell anymore, they don’t touch any more, they get hit by a bus when they cross the street because they are not alive, they’re not looking. I am not happy in the 21st century. I live in the 18th century, I live in the Middle Ages.”

And the Towers, I persisted?

“They are human in my heart. They are my friends. So when people say what did you feel that day when the Towers were destroyed, I cannot answer that question. Because how can I talk about the loss of two architectural marvels when thousands of human lives were taken that day?”

Now 40 years later, Petite is 65 and has barely changed.

“In the invitation [to the anniversary event], I say that although it is the same wire, the same man, the same apparatus, this time you are going to be able to see my face, to see my choreography,” Petit says. “And I think that is very interesting.”

I pointed out that Robert Leacock, the documentarian, who is filming the walk, told me that when Petit is on the wire his face constantly alters expression.

“Oh, yes,” he said. “And my friends say that when I get on the wire, even if I practice, my face changes and I become younger. But younger by 10 years, you know! It is a strange thing. And this is something I have witnessed in many of my friends who are performers. For example Francis Brunn, the greatest juggler in the world, was my best friend for many years until he died. And I would see him as an old man backstage. He would have all kind of problems. And he would arrive onstage...he would do his eight-minutes act…” Petit mimes zest, youthfulness.

“... and he would go backstage...and he needed to sit down...

“We know we’re getting old, some people retire. I don’t accept that. You are going to stay young. Of course, your body will refuse to obey you and if you are wise you will stop, because it is not nice to see a limping wirewalker. But until that day, until my legs refuse to obey me, I refuse to count the years, and I refuse to pay attention to ‘You should retire!’

“Three hours a day I practice. And they say, ‘But what are your limitations?’ I say, ‘No, I am better at 65 than when I was an arrogant little bastard at 18, trying to prove myself.’ Now I don’t need to prove anything. And the more you know, the more you realize you have to learn. Not to prove but to improve is really where I am at. And I think I am at the top of my life as a wirewalker. I think the 50 years of learning has put me in a position where I am really in command. I do not have the suppleness of 20 but I have something much more important… And you see that when you see the show. You’ll see the transformation when I do the first steps, you will see the transformation. I get younger, I am so happy!“

It was a good day for the anniversary walk; sunny but not blistering.

The LongHouse gardens were—well, I urge you to go and see for yourself sometime. Several rows of chairs were set in front of the pond, which was so rich with exotic vegetation that you half expected to find Claude Monet parked there with an easel. There were so many lines above it crossing in different directions, though, that it was hard to puzzle out just where we would see Philippe Petit walking across the sky. Then, a sharp-eyed woman pointed out a ladder leaning against a tree on the side of the pond. “He’ll come towards us,” she guessed.

And so it proved. Petit appeared in white and began walking the wire sometime after six. During his crossings two performers with whom he has worked before did their stuff from time to time. Paul Winter played the saxophone and Melissa Leo, the actress, read texts written by Petit himself.

I had been unsure how I was going to react to his performance. This was not the Impossible—the Eiffel Tower, the Sydney Opera House—this was a walk above the LongHouse pond. But Philippe Petit had spoken to this issue earlier. “I have the luck of not being born in the circus,” he told me. “So I didn’t follow the tradition of the costume, the pratfall, the danger. I came from the world of opera, theater, poetry, art, and therefore when I learned by myself the wire what I wanted to do was not to frighten my audience but to inspire them. I dedicated myself to walking, you know, the art of walking, which is so simple that it is extremely difficult.”

And to do what for most is not possible?

“Yes. Yes. People are touched by seeing somebody walking in the sky because they cannot imagine being there. It is like a miracle. And to me too when I see a wire walker, talented or not, think a miracle is happening now!”

It’s a matter of self-definition. Petit isn’t Nik Wallenda, walking Niagara Falls, and he’s certainly not Evel Knievel. He makes performance art.

Petit walks the wire back and forth four times, varying the walks with little routines from time to time. At one moment, he walks forward jauntily, as though walking onto a dance floor, at another he lifts one leg, then another. At yet another, he lays down full length on the wire. I learn that these were precisely the routines he had used during Le Coup, as he calls the World Trade Center walk, and that this wire is the same length as the World Trade Center wire. It’s a very specific piece. Like a battle scene, frozen in time on a Greek vase.