Arne Glimcher, who founded the venerable Pace Gallery back in 1960, is a man of many talents. Besides representing a stable of some of the most celebrated contemporary artists working today—including Chuck Close, Kiki Smith, Fred Wilson, Sterling Ruby, and Zhang Huan—Glimcher is an accomplished art writer, film producer, and director.

Click Image to View Our Gallery of ‘Picasso and Braque Go to the Movies’

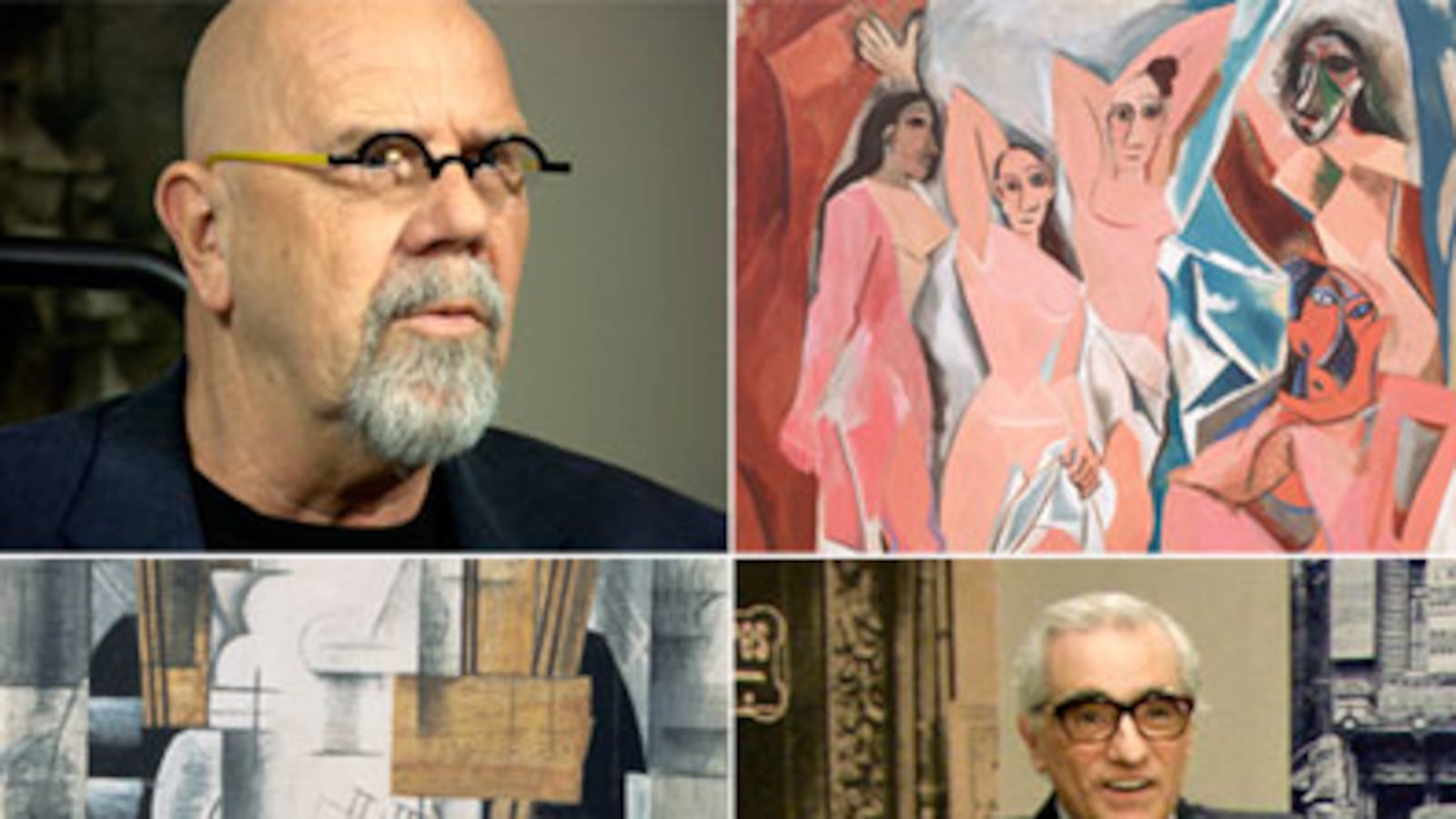

Now Glimcher is tackling his first documentary film, Picasso and Braque Go to the Movies, which had its New York premiere at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and began its nationwide theatrical tour at New York’s Cinema Village last week. Glimcher rewrites the history of Cubism by making a convincing argument for the influence of film, aviation, and technological advances on Pablo Picasso, George Braque, and their circle of creative friends at the turn of the 20th century.

Picasso and Braque Go to the Movies grew out of the dynamic 2007 PaceWildenstein gallery exhibition Picasso, Braque and Early Film in Cubism, which was curated by art historian Bernice Rose and presented paintings, collages, posters, short films, and early film equipment. A former Museum of Modern Art curator, Rose investigated Glimcher’s idea that Picasso’s depiction of multiple angles in portraits had a relationship to camera angles in cinema and discovered that Picasso’s first motion picture viewing took place in Barcelona in 1896 and he made a painting after the battle scene he had witnessed in the film.

• Rachel Wolff: The Power of Picasso • Art Beast: The Best of Art, Photography, and Design It was Ari Emanuel, Glimcher’s Hollywood agent, who suggested the exhibition could be turned into a documentary film, and Martin Scorsese was brought on board as the film’s producer and narrator. Scorsese introduces the film by declaring, “In 1895, it would be the Lumiere brothers in Paris advancing Edison’s technology and introducing the cinematograph projecting motion pictures. It was one of a range of remarkable new technologies that promised the annihilation of time and space, as it was known.”

The relationship between painting and film, as well as thoughts about Cubism, are explored by some of Glimcher’s gallery artists, including Lucas Samaras and Robert Whitman, who have both worked with film and time and space art, and painters, including Close and Eric Fischl, who provide their perspective of Cubist painting and the continued influence of film on artists. Julian Schnabel, who started out as an artist and has since established himself as a formidable filmmaker, says, “When you look at a painting you get everything immediately: the beginning, the middle, and the end and then you get the beginning, middle, and end again. The process of time, the temporal quality of that is the time spent looking. When you’re watching a movie, you have to wait until it’s over to get the full, resolved object that you’re going to digest afterward.”

Film historians Tom Gunning, Kim Tomadjoglou, and Jennifer Wild discuss the simultaneous development of early cinema and its high visibility in Parisian cafés, department stores, circuses, and hundreds of city cinema palaces, while Rose talks about the creation of Cubism and links the filmed movements of dancer Loie Fuller and the magical films of Georges Méliès to Picasso’s breakout painting Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, which she labels as “mediating between stasis and movement.”

Picasso biographer John Richardson discusses Picasso’s love of Charlie Chaplin films and cowboy movies, while art scholar and author Adam Gopnik references Picasso and Braque’s nicknames for one another, Orville and Wilbur (after the Wright brothers), and says, “The deepest resemblances between what Picasso and Braque were doing and what the first filmmakers were doing comes in the sense of permissions given, old restrictions removed, possibilities open.”

The marriage between the comments and the visuals is compelling. “Bernice and I saw over 300 films,” said Glimcher, after the screening, “and it was really a challenge to select the pieces of film we were going to use. Our editor, Sabine Krayenbühl, was amazing. She kept coming up with more and more imagery when we needed it. It was thrilling to see a whole period of film that is generally not known. Marty Scorsese, who is an incredible film historian, was not familiar with this period of film. When I showed him the first cut of the film, he said, ‘Wow, thank you. I’ve learned a lot about cinema from this movie.' ”

Informative and inspirational, Picasso and Braque Go to the Movies is a must-see for lovers of both art and film.

Plus: ">Check out Art Beast, for galleries, interviews with artists, and photos from the hottest parties.

Paul Laster is the editor of Artkrush.com, a contributing editor at Flavorpill.com and Art Asia Pacific, and a contributing writer at Time Out New York and Art in America.