In the world of professional sports, table tennis is Rodney Dangerfield. For most Olympic spectators, it falls somewhere between archery and trampolining on the roster of must-see events. Conan O’Brien recently tweeted: “Athletes at the Olympics are being issued 15 condoms each. Or as the men’s table tennis players put it, ‘14 condoms too many.’”

As a former Junior Olympian table-tennis player myself, I can attest: when competitive Ping-Pong is your best sport in high school, it doesn’t exactly prove your physical prowess. Typical reactions to my game of choice? “You must have really strong wrists.” “Do you play like Forrest Gump?” “Do you play real tennis too?” “My grandmother is the Palm Beach retirement-home champion—you guys should play sometime.”

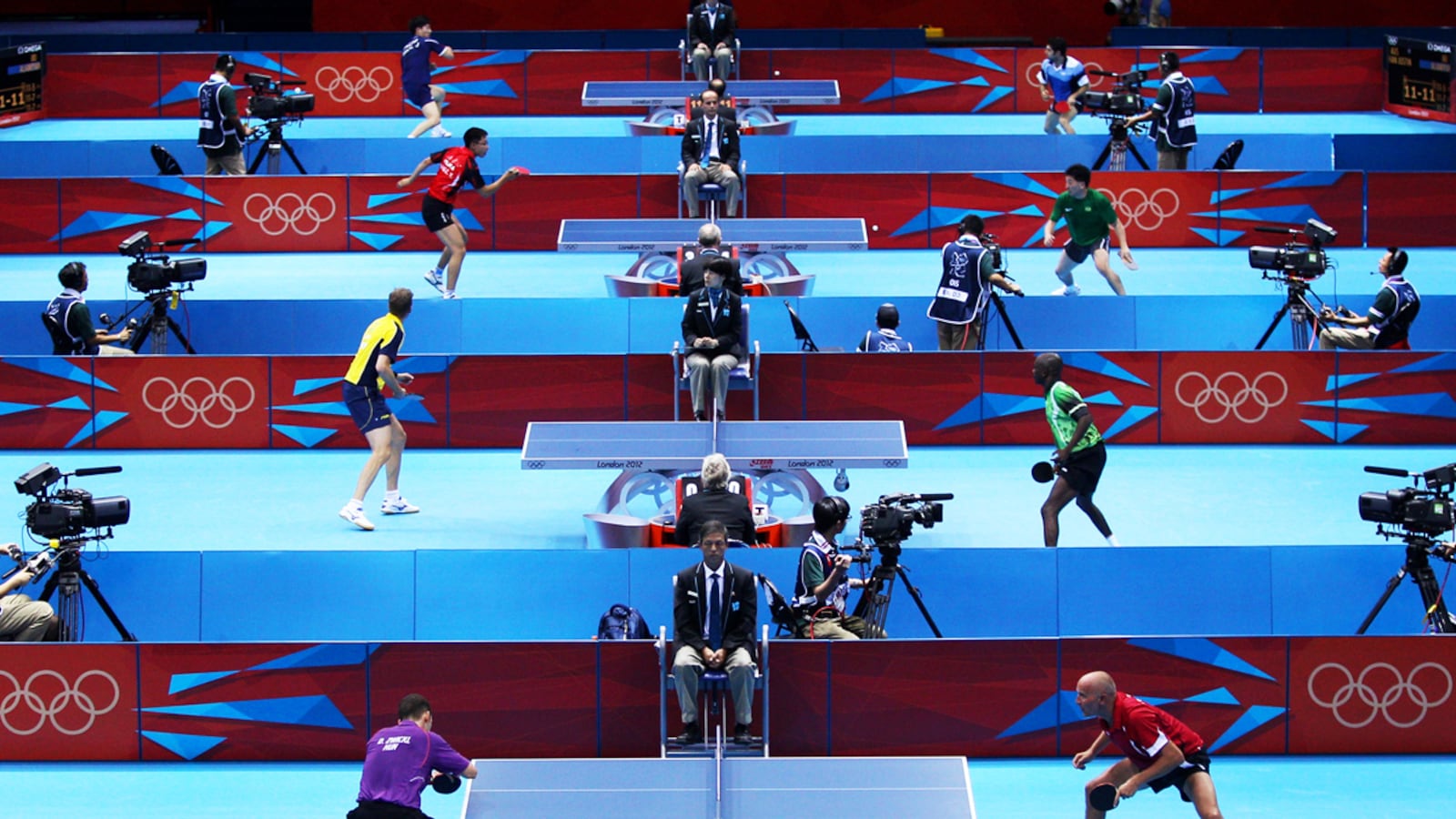

Yet every four years when the Summer Olympics arrive, I hold out hope that the Games will, once and for all, help table tennis transcend its stereotype as a wimpy parlor game, convincing Americans that its players are in fact “real” athletes—and that it’s just as worthy a spectator sport as, say, synchronized swimming. I was especially excited about this year’s coverage, which for the first time included livestreaming of all matches, offering it far more exposure than its usual 3 a.m. network time slot.

So in the midst of this Olympic excitement, I was dismayed to read American Ping-Pong legend Marty Reisman declare on The Daily Beast that modern competitive table tennis is “unwatchable,” lamenting that, thanks to today’s high-tech equipment, it consists simply of “imperceptible flicks of the wrist rather than athleticism.” If we’d lost Reisman, Ping-Pong hall of famer and evangelist for the past six decades, had we simply lost?

As a passionate believer in table tennis’s future, I feel it my duty to set the record straight: not only is competitive Ping-Pong supremely athletic, but it’s just as thrilling to watch as it was in Reisman’s day, if you know what to watch for. Competition-level Ping-Pong is like running, boxing, and playing chess all at once. And the training regimens are just as demanding, incorporating complex practice drills at the table and intense conditioning for core and lower-body strength. Check out the thigh muscles of the competitive table-tennis players—they’re ripped!

All of which was apparent in this year’s Olympic table-tennis matches, particularly in the games of Northern California’s Ariel Hsing, a 16-year-old honors student and Ping-Pong phenom. During the third-round women’s singles competition, Hsing delivered an inspiring performance against eventual gold-medal winner Li Xiaoxia, coming closer to defeating China’s formidable star than any other competitor. Think Rocky versus Apollo in the original boxing classic.

Although Hsing didn’t win, her performance earned her, and American table tennis, the respect of the sport’s international community. “Ariel Hsing's match was the highlight of the Olympics for me,” NBC table-tennis commentator Ari Wolfe told me. “America needs someone to be the face of table tennis, and Hsing has that potential.”

While modern table tennis is played much differently than during Reisman’s time, when players used sandpaper paddles and rallies were often drawn-out wars of attrition, it’s evolved to be even more rigorous and awe inspiring. Still, Reisman has linked the sport’s decline in this country to the introduction of sponge-rubber paddles in the 1950s. These paddles create “tiny technological advantages,” he wrote, allowing for players to generate remarkable spin shots—which, he argues, makes the game less about skill and more about “deceit and deception.”

But to watch two elite players counterlooping back and forth with gravity-defying spin is remarkable. (The money shot in modern table tennis, known as “the loop,” requires a powerful hip-waist-shoulder twisting motion and forearm snap, unleashing a fierce topspin on the ball as it accelerates in a downward arc.) Has the modern paddle actually made the sport less exciting or skillful? Best to judge for yourself: compare this video of this year’s U.S. Olympic trials winner, 17-year-old Michael Landers, with how the game was played in Reisman’s day.

And yet, while America was a formidable player on the world table-tennis stage in Reisman’s era, today it’s relegated to obscurity. Aside from Hsing’s performance in women’s singles, the U.S. put up a mediocre showing at this year’s Games. Timothy Wang, our lone qualifier for men’s singles, lost in the first round to North Korea’s Kim Song Nam, and our women’s team lost in the first round to eventual silver medal winner Japan.

Still, there are signs of hope.

Over the past few years, as Reisman points out, Ping-Pong as a social sport has soared in popularity, with tables popping up in trendy bars and hotels—giving it an aspirational quality. And with the success of New York’s SPiN, a chic Ping-Pong parlor co-owned by Oscar-winning actress Susan Sarandon, it now boasts a hub in the world’s most trendsetting city. (Last week, the owners announced plans for a Los Angeles location.) The genius behind SPiN, which draws both elite players and casual bar-goers looking for an alternative to darts or bowling, is that it celebrates table tennis as a competitive sport and a social activity. With its cool factor upped, perhaps would-be amateur players will feel emboldened to adopt it as a competitive sport.

Outside the bar-and-basement scene, the sport’s infrastructure is slowly improving as well. The first nationwide table-tennis league is in the works, and there are now more than 50 full-time clubs in the U.S., as well as a collegiate league of 141 schools. America’s junior players are competing and excelling in more international tournaments, shaped by an influx of European and Chinese coaches. And over the past few years, under the guidance of founder Ben Nisbet, the American Youth Table Tennis Organization has introduced the game to more than 1,500 kids in New York City's low-income neighborhoods through after-school programs and camps.

Table tennis has also benefited from a recent rise in star power: along with Sarandon, comedian Judah Friedlander is a regular at SPiN and a vocal advocate for the sport. On the highbrow end, Bill Gates cheered on Hsing in London, and Warren Buffett has invited her to the annual Berkshire Hathaway shareholders party after recognizing her talent at age 9. Crossword guru Will Shortz founded the Westchester Table Tennis Center, one of the Northeast’s largest centers. And Top Spin, a documentary about the Olympic quests of Hsing, Landers, and 16-year-old Lily Zhang, is slated for release early next year.

On top of all this, China’s lock on competitive table tennis may be loosening. Yes, the country dominated the sport at this year’s Olympics, sweeping all four possible gold medals. But there’s evidence that Ping-Pong’s popularity is waning in the country since the era when Mao declared it the national sport. We’d be wise to seize on this dip as an opportunity for Americans to break into the elite arena. Three crucial steps from here? Incorporating table tennis into high schools on a varsity level, gaining recognition as an NCAA sport—and enabling professional players to support themselves financially. Here's looking at you, Gates and Buffett.

Like millions of other kids in this country, I began playing Ping-Pong in the basement of my childhood home. When I was 12, a family friend told us about the Syracuse Table Tennis Club, and I begged my dad to take me. One evening, he finally acquiesced. The building was dilapidated; the neighborhood sketchy; the floor dusty. But the game was played like nothing I had seen before. The pace, rhythm, crazy spins, personalities, and, as I quickly learned, unique underground subculture were addicting. Before long, weekends were spent competing in regional tournaments, winter breaks training at the National Table Tennis Center in Maryland, and Thanksgivings playing in the U.S. Open teams championship.

Now in my thirties and having graduated from medical school, I rediscovered the sport a few years ago when SPiN opened in New York. I’ve started playing competitively in tournaments again and prosthelytizing to friends who’ve only played casually in the past. The sport has been a great stress reliever after long days in the hospital, and has led to lasting friendships with people from all over the world—people I would never have crossed paths with otherwise.

In high school, I was dubbed “the Lone Ping-Pong Player” in a profile that ran in my school’s newspaper. Though I loved playing, I felt isolated at times. Now, seeing SPiN packed with crowds of players on weekend nights, I’m prouder than ever of my sport. I hope America feels the same way soon.