The shooting at the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh one week ago is not simply the act of a lone madman, nor is it an act of exclusively anti-Semitic violence. It is part of a broad and flexible ideology that unites several threads of white supremacy, anti-Semitism, antifeminism, and anti-immigration rhetoric: the white power movement.

This movement and its violence are not a recent problem. White power activists did not begin their online hate with Gab or Twitter. They had decades of social networking experience before the invention of Facebook. There can be no doubt, furthermore, that theirs was a coherent social movement. Its activists shared not only ideologies and common violent goals, but also deep personal relationships, including marriages, childcare, counseling, and religious leadership.

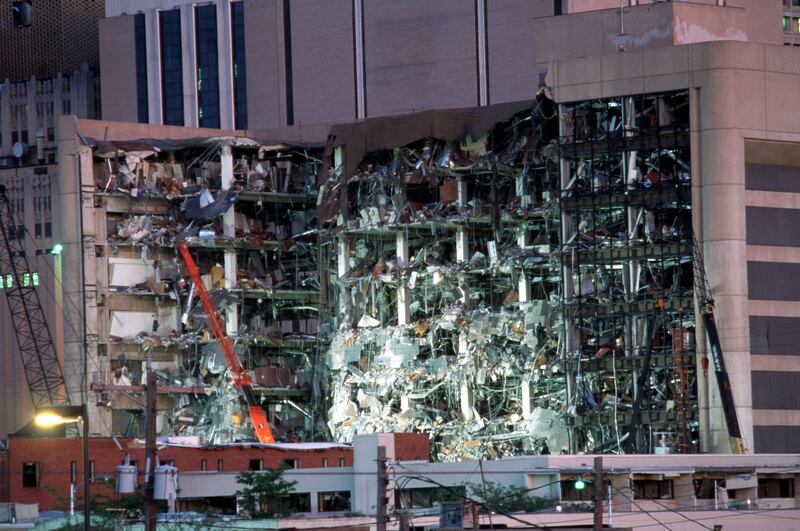

I have spent a decade studying an earlier incarnation of the white power movement, which gathered extremist groups and activists together in the late 1970s. It united Klansmen, neo-Nazis, racist skinheads, radical tax resisters, and others in common cause. This movement, organized around the paramilitarism and weapons of the Vietnam War, turned even more violent in 1983, when it declared war on the state. It used cultural currents and political events to recruit and radicalize its members, and grew into the militia movement beginning in the late 1980s. Its largest act of mass violence, the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing, killed 168 people including 19 young children.

Terrorist Bomb Attack on Oklahoma Building

Robert Daemmrich Photography Inc/GettyThis movement left behind thousands of pages of archival evidence, including the writings and actions of its members, reporting on their violence, and declassified government documents from the people charged with preventing and prosecuting such acts. This repository enabled me to trace not only the rhetoric and ideology of these activists, but also the actions they took across decades to attempt race war. It is a terrifying record, including assassinations, infrastructure attacks, attempts at mass poisoning, manufacture of weapons, training in urban warfare, paramilitary camps, and obtaining weapons stolen from military posts and armories.

Investigative journalists, watchdog groups, and social media sites have begun the difficult work of unraveling the specifics of alleged mass murderer Robert Bowers’s networks, his connections with other activists and groups in the alt-right, and the other social relationships that place his violence in context. But so, too, can we use the historical archive of white power activism to make sense of this event.

Robert Bower

PENNSYLVANIA DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATIONFirst, and most critical, this is not only an act of anti-Semitism. Certainly anti-Semitism represents one current of this ideology, and anti-Semitism brings with it centuries of history and its own apparatuses of understanding. But we can learn more from approaching this as an act of white power violence.

White power activists from the 1970s onward understood anti-Semitism as one strand of a linked and coherent worldview. White power proponents believed that Jews and other malevolent international forces conspired to control the federal government, the United Nations, the banks, and more. They called this conspiracy the Zionist Occupational Government (ZOG), and, later, the New World Order. They understood the stakes of this conspiracy as tantamount to racial annihilation: that is to say, they believed that social issues like immigration, abortion, LGBT rights, and more were thinly veiled attempts of a Jewish conspiracy to threaten the future of the white race.

Bowers wrote in his final post on extremist-friendly social media site Gab, about “…invaders that like to kill our people. I can’t sit by and watch our people get slaughtered. Screw your optics, I’m going in.”

This is clearly an anti-Semitic message, but we would miss critical information if we ignore what he repeated twice: “our people.” The people here are white people. This is how the shooting at a synagogue relates to the other posts, where Bowers expresses his concerns about the caravan of immigrants, still thousands of miles away, coming to the border. In this ideology, anti-Semitism is linked to anti-immigration. Both of them are understood as related not only to the soft demographic changes perceived in popular culture as obliquely threatening the privilege of white men like Bowers; in this ideology, they are experienced as apocalyptic in scale, as the coming annihilation of the white race.

Significantly, Bowers reposted references to ZOG. He also wrote about the idea of Jews descending from Satan. This belief appeared in the earlier white power movement as Christian Identity and Dualism, political theologies that posited that white people were the true lost tribe of Israel while Jews and people of color descended from either Satan or animals. This is a significant statement not only for its dehumanizing claim, but because it is tied to an overtly violent faith. Christian Identity foretold an imminent end of the world in which believers would have to take up arms to clear the world of Jews, people of color, and other enemies before the return of Christ. In other words, it attempted to cast white power violence as a holy war.

Bowers has a number of other ideological ties to white power which are immediately visible in his social media. He repeatedly invoked “14” and “88,” which are white power slogans that refer to the Fourteen Words (a phrase that calls for the protection of white children against threats of racial annihilation) and a coded “Heil Hitler,” respectively. He also posted several positive references to the Holocaust.

Such statements are both shocking and anti-Semitic, but reporting the Tree of Life shooting as an act of anti-Semitic violence (and not exploring it as connected to a broader white power ideology) is a problem: it contributes to a misunderstanding of such events as one-off attacks, acts of lone wolves, and the work of madmen.

In fact, such events are connected with one another and motivated by a coherent political ideology.

The white power movement has pursued cell-style organizing since 1983, emphasizing the work of one or a few activists without ties to leadership. Its members, by design, do not always make clear their connections to one another. This strategy, often called “Leaderless Resistance,” was first implemented to foil government informants and criminal prosecutions. But its larger legacy has been its power to blur and erase the organized white power movement from public understanding.

Furthermore, social media played an important role in how the white power movement connected activists in common cause, and it has done so for decades. White power activists got on computer message boards in 1983-84, with the codeword-protected Liberty Net. These message boards included hit lists, but they also included personal ads and similar materials designed to join white power groups and activists in a social network. They used such message boards to circumvent laws prohibiting the distribution of hate literature over the U.S. border—in other words, to build a transnational movement. And this initiative was important enough that they used the money stolen from armored cars to purchase computers for groups that didn’t have them. One activist traveled around the country, teaching groups how to get on the message boards.

The historical archive shows us that events of mass violence motivated by white power movement organizing tend to be connected not only to one another, but also to more public-facing rhetoric and activism. In public, the earlier white power movement pursued political runs and suit-wearing talk show appearances by people like David Duke. It posted fliers, ran newspapers that reached not only movement faithful but casual members, and held public events designed to attract and recruit people.

It will be critical, in the coming weeks and months, to closely evaluate the relationship between public-facing white power activism in the present moment, such as rallies and altercations like the one at Charlottesville last year, and underground organizing that gives rise to mass violence like the 2015 shooting of Bible-study worshippers in Charleston by Dylann Roof. Roof, radicalized online by the social networks begun decades earlier, wore a Rhodesian flag patch in photographs, symbolizing a nation that had never existed in his lifetime, and connecting his activism to that of the earlier movement.

Tragically, the resources devoted to establishing such ties have been sparse at every level. FBI policy limited investigations into acts of white power violence beginning in the late 1980s, after failed trials. Policy dictated that individual crimes were to be investigated without emphasis on the movement that fomented them. Disasters in encountering white power activists at Ruby Ridge and apocalyptic fellow travelers at Waco in the early 1990s further damaged such investigative resources. As a result of these policies, the Oklahoma City bombing is still widely understood as the work of a few actors—even when multiple accounts have decisively placed the event within the context of the broader white power movement.

PITTSBURGH, PA - OCTOBER 31: Mourners visit the memorial outside the Tree of Life Synagogue on October 31, 2018 in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Eleven people were killed in a mass shooting at the Tree of Life Congregation in Pittsburgh's Squirrel Hill neighborhood on October 27.

Jeff Swensen/GettyIf there is a way to move forward from the horror of the Tree of Life shooting, it must include a change in the way that we think about these events. When violence has an ideology, we can understand it. When violence has a history, we can learn how to better confront organized racism and anti-Semitism, and how to prevent future recurrence.

Kathleen Belew is an assistant professor of history at the University of Chicago and author of Bring the War Home: The White Power Movement and Paramilitary America.