While you’re out collecting Pokemon on your phone this week, a Google spinoff company will be busy collecting data about you.

Over the course of just a few days, the former internal Google startup Niantic has acquired a gold mine of personal information through its smartphone application Pokemon Go, a new augmented reality game which encourages players to go out in public, visit landmarks, and collect cartoon monsters.

According to Forbes, the game is already close to surpassing Twitter in the number of daily active users on Android—and it was only released on July 6th.

Each of these users is providing Niantic with a wealth of information about their location. And with aspiring Pokemon trainers signing up in record numbers, sources tell The Daily Beast that Niantic’s database of personal data has become a ripe target for hackers, criminals, and corporations, practically overnight.

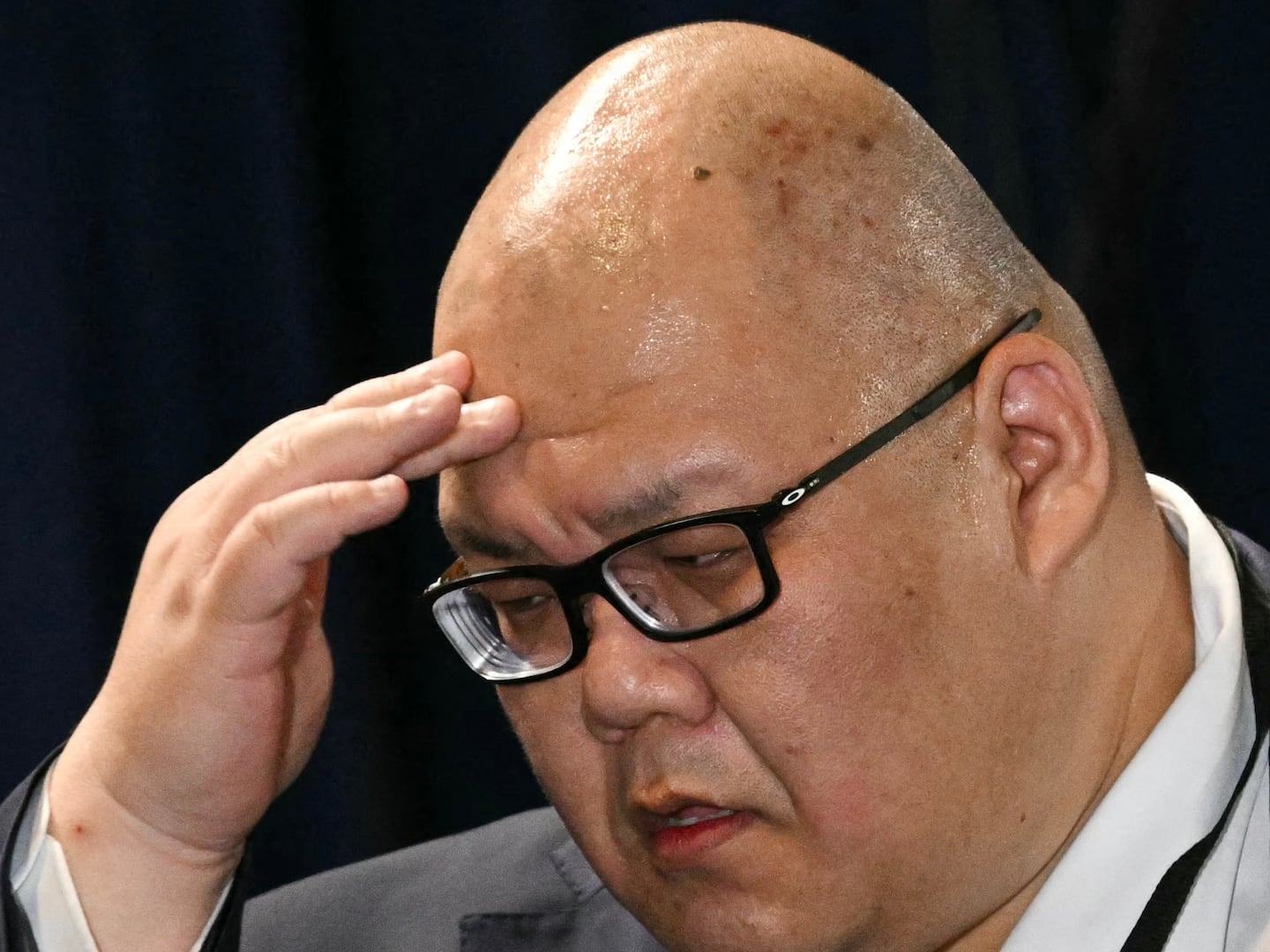

“When they hit 25 to 20 million records, they’re going to be breached, and they’re at 10 million right now,” said Gary Miliefsky, who advised the U.S. Department of Homeland Security in the early 2000s and is currently the CEO of the cybersecurity firm SnoopWall.

Pokemon Go collects a vast amount of information from its users. On Android devices, for example, the application asks for access to the user’s camera, contacts, GPS location, and SD card contents. The sign-up process also asks for a date of birth. Although other popular games can make big asks when it comes to device permissions, Pokemon Go requires an active WiFi or GPS signal at all times in order to play. In other words, it has to know who you are.

In addition, Niantic’s Privacy Policy gives the company wide latitude for using this information. Niantic can hand personally-identifiable information (PII) over to law enforcement, sell it off, share it with third parties, and even store it in foreign countries with lax privacy legislation.

“Normally, you won’t see that in an app,” Miliefsky noted, referring to the fact that an entire section of the privacy policy was dedicated to outlining the use of foreign storage.

All of this should give potential users pause before jumping on the Poke-wagon, added Drew Mitnick, policy counsel for the digital rights organization Access Now. Unless you read the fine print, Mitnick says, you don’t know how far your PII can travel.

“It is becoming abundantly clear that the permissions screen, which evolved to provide users a screenshot of information that apps can access, no longer provides adequate notice on how that information is collected and used,” he told The Daily Beast.

It’s unclear exactly where Niantic might be sending your data, and the company has so far offered scant details on how it plans to store the huge data trove.

Niantic did not immediately respond to The Daily Beast’s request for comment on the potential security and privacy risks associated with Pokemon Go.

The company promises in its Privacy Policy that it is taking “appropriate administrative, physical, and electronic measures designed to protect the information.” But hackers have increasingly been targeting large databases of PII—and successfully exploiting them.

In February of last year, for example, health insurer Anthem. announced that hackers had accessed the personal information—including names, birthdays and Social Security numbers—of 78.8 million customers.

A few months later, news broke that hackers had penetrated an even more sensitive database: that of the U.S. government’s Office of Personnel Management (OPM). The hackers, reportedly from China, accessed highly sensitive information on 21.5 million government employees, including details of infidelities and drug abuse.

And if the U.S. government can’t keep hackers out, Miliefsky is doubtful that a small startup in San Francisco could.

“This is a little company,” he said. “It’s in a suite in San Francisco. Where do they host the data? How do they encrypt it?”

The data, it turns out, may not even be hosted in the United States. The Privacy Policy states that PII “may be transferred to, and maintained on, computers located outside of your state, province, country, or other governmental jurisdiction where the privacy laws may not be as protective as those in your jurisdiction.”

Both Mitnick and Miliefsky are concerned that Niantic has not addressed encryption.

“It’s unclear if all of that data being collected by Pokemon Go players is encrypted or if some hacker is going to be able to break into these databases of sensitive information,” said Mitnick.

“A company like that should publicly state if they have taken the proper measures or not,” added Miliefsky. “You should be able to ask them: Do you encrypt all the data? Who has access to the keys? Do you background check all your employees?”

Hackers could make a profit by selling Pokemon catchers’ data on the black market or to foreign governments, Miliefsky said. There’s also the risk for credit card fraud—Pokémon GO uses in-app transactions—as well as identity theft and fake insurance claims.

And although Niantic promises to be taking “appropriate” protective measures, it concedes in its Privacy Policy that it “cannot guarantee the absolute security of any information.”

Even if personal information from Pokemon Go is kept safe from illegal breaches, it can still be legally sold to and shared with third parties.

In the Privacy Policy, Niantic notes that it considers PII of its users to be a “business asset” that can be sold to another company in the event of a merger, acquisition, or asset sale. Niantic can also share personal information with third parties for the purpose of “performing services” and it can give aggregated, non-identifying information to third parties for “research and analysis, demographic profiling, and other similar purposes.”

If Pokemon Go players are going to surrender all of that information to play, Mitnick believes that they should at least be told more about where it goes after it is collected.

“It’s increasingly necessary for users to have the option to see how certain types of data are used in the app and the length of time that the company holds on to that information, as well as any additional analysis that it is used for,” he said.

Niantic’s history with Google also raises questions about the PII gathered from Pokemon Go. The startup is now an independent entity from its former parent, but it co-developed the game using millions of investment dollars from the Silicon Valley search giant. Additionally, users can sign into the app through their Google account, allowing Niantic to collect even more information contingent on your Google privacy settings.

As TechCrunch reported, it would be “prudent to expect some of your [aggregated] location data to end up in Google’s hands” given the closeness of the relationship but Niantic did not confirm this possibility

Perhaps most worrisome, criminals could also have a vested interest in the information they can glean from simply using Pokemon Go.

Nine people in Missouri have already reportedly been robbed at gunpoint after visiting specific in-game locations, as Gizmodo reported. Pokemon Go encourages users to collect items at real-world locations known as PokeStops, allowing criminals to anticipate places where players are likely to gather.

Even more troubling is the fact that criminals can use items called “Lures” at PokeStops to attract more Pokemon—and therefore an influx of players—to a precise location. As the O’Fallon, Missouri Police Department noted on Facebook, this is how some recent armed robberies they are investigating were likely conducted.

And according to Miliefsky, the app won’t just appeal to petty thieves; it could also be used by pedophiles to predict children’s movements.

“The phones are geolocating children,” he said. “This is a big deal in my mind. This app goes too far. It’s not obvious because people don’t read the fine print.”

While most customers might skip over the worrying privacy policy, Niantic itself might not even realize what security problems lie ahead. Just days ago, the company was a startup aiming to create the next big—and lucrative—smartphone app.

Niantic succeeded wildly, gaining a huge data set in an unprecedentedly brief time. Now, the company has to keep that trove of personal information safe—or millions of its Pokémon-catching customers will be left vulnerable.