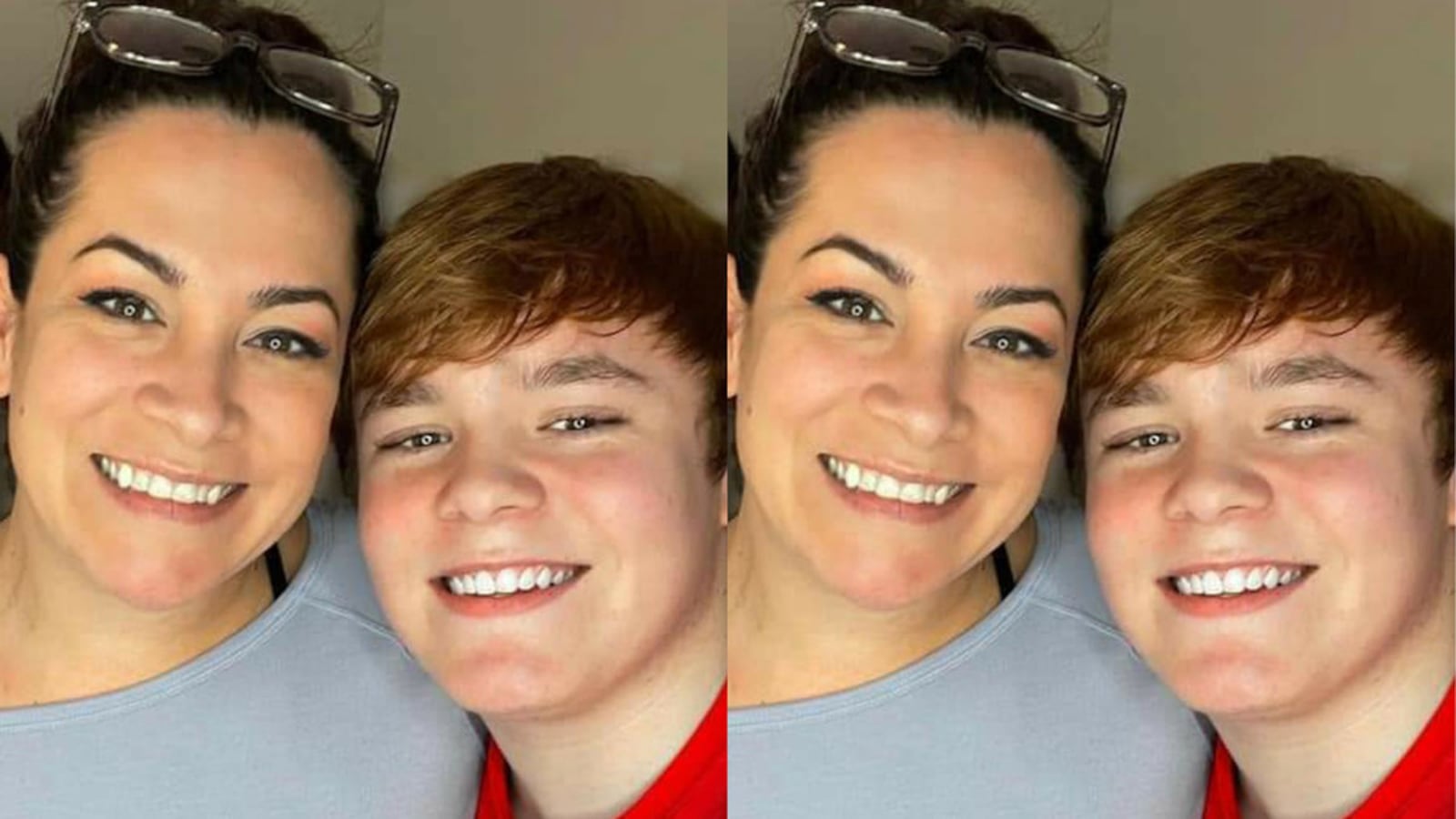

Rosie Diven, a mother of three in rural South Carolina, had no idea her 16-year-old son had COVID-19 until a fearsome syndrome nearly killed him.

Branson Diven had been vomiting and suffering a loss of appetite when Rosie brought him to an urgent care center near their home in Hartsville on Dec. 10. He did not have classic COVID symptoms such as a sore throat or a cough, and after testing negative for COVID and positive for flu, he was sent home under the assumption he would soon be better.

Six days later, Branson seemed sicker.

“I said, ‘We got to go back,’” Rosie recalled.

On Dec. 16, they returned to the urgent care center. The family nurse practitioner on duty gave an instant reappraisal.

“We walk in the door and she says, ‘I don’t know what this is but it’s not the flu,’” Rosie remembered.

They were sent to McLeod Children’s Hospital in Florence, where Branson tested negative for COVID and flu but seemed to be in such bad shape that he was airlifted to MUSC Shawn Jenkins Children’s Hospital in Charleston, one of the best pediatric facilities in the country.

“As soon as they said they were going to call the helicopter, I knew it was pretty serious,” Rosie said.

At Shawn Jenkins, Branson again tested negative for COVID and flu, but he had antibodies from an infection of some kind. Rosie was told that Branson was suffering from MIS-C—the acronym for multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children. They explained that the condition is a delayed inflammatory response to COVID that can come as if from nowhere weeks or even months after an infection—even an asymptomatic one.

The potentially deadly disorder—which can target the major organs all at once—spiked in the early days of the pandemic, when the early variant of the coronavirus was sweeping the country. It generally was not triggered during the Delta variant that emerged last year.

The new highly contagious Omicron variant filled Shawn Jenkins and many other hospitals with a record number of pediatric COVID patients. But the doctors had hoped that Omicron would act like Delta and not trigger MIS-C.

With the arrival of Branson and another pediatric patient with MIS-C, the doctors at Shawn Jenkins figured he likely had Omicron and that it carried a threat of MIS-C. They checked an inflammation marker called ferritin in Branson. The normal level is between 40 and 200.

“His was 80,000,” Rosie said.

The syndrome had simultaneously attacked Branson’s heart, kidneys, and liver.

“They said he probably would not have woken up Friday morning if I hadn’t taken him in Thursday night,” Rosie told The Daily Beast. “He was going fast.”

Rosie said Branson seemed “a little out of it” as he was admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit. But his spirit remained remarkably buoyant right up to when he was sedated before being intubated.

“On his deathbed, making other people laugh,” Rosie marveled. “That’s how he is.”

Branson has no memory of his five days on the ventilator to facilitate 24-hour dialysis. Rosie and her husband, Jonathon, stayed in the room with him, sleeping on the sofa as he fought on.

Branson had not been vaccinated and Rosie was coming to understand the importance of the jab.

“I definitely changed my opinion about vaccination,” she told The Daily Beast.

Branson’s storming immune system quieted and he was taken off the respirator in time for Christmas. His younger sisters, 14 and 15, arrived and the family spent the holiday at the hospital.

On Dec. 30, Branson was discharged with prescriptions for eight medications.

She reported that nobody at the hospital would tell her if the vaccine could have prevented the MIS-C. At that point, Shawn Jenkins and 23 other children’s hospitals had not completed a major study to answer that question. The results were released on Jan. 10 and summarized to the press by Dr. Elizabeth Mack, chief of pediatric critical care at Shawn Jenkins, as well as a principal investigator in the study and an author of the report.

“The bottom line is MIS-C is a vaccine-preventable disease,” Mack said.

Data posted by the South Carolina Children’s Hospital Collaborative indicates that the one MIS-C patient who was on a ventilator as of Jan. 20 is also unvaccinated. The record total of 61 children currently hospitalized for COVID includes six who are vaccinated, 28 unvaccinated, and 26 who are under 5 and too young for the jab.

“People are worried about the risks of a vaccine,” Mack noted. “What they often don’t consider as a risk of the disease… We know the risks of the disease and we know the risks of MIS-C. So, I think the risk ratio is certainly in favor of vaccination.”

She offered a simple calculation for those who downplay the risks children face in the pandemic.

“If you’re a parent of a child in the hospital, one child is a lot,” she said.

Nobody knows that better than Rosie. She and her husband did not immediately convey to Branson how it could have gone.

“We didn’t quite come and tell him that he was close to not making it,” she said.

But Branson seemed to have figured it out, learning exactly the right lesson from his brush with death.

“He’s very appreciative of everything,” Rosie said. “Everything’s amazing now.”

She reports that he is doing his homework, including what she figures is his least favorite subject.

“He’s doing math, believe it or not,” she said.