The FBI just issued its Uniform Crime Report for 2016 and no one will be surprised to learn that violent crime shot up since the 2015 report. Nor will any eyebrows rise when we note that the biggest increase occurred in our most populous cities. Take murder and manslaughter, for instance, which provide the most accurate crime data. For all U.S. cities, killings rose 8.8% since 2015, but for cities with a million people or more the homicide spike was over 20%. Another significant statistic is the increased involvement of African Americans both as homicide victims and perpetrators. In Chicago blacks (32% of the city) were over 78% of the murder victims in 2016, and nationwide (13% of the population) they were more than 52% of the victims.

At the same time that these disturbing crime figures were released the Census Bureau was producing some paradoxical poverty figures. In every one of the 25 most populous metro areas in the United States poverty declined from 2015 to ’16. For the African American population in deep poverty (less than 50% of the poverty level) – a population at high risk for violent crime – there has been a modest but steady decline since 2012. In 2012, 13.5% of the black population was in deep poverty; in 2016 that figure fell by 807,000 to 11%.

Juxtaposed, these statistics present an anomaly that has baffled analysts for over a century. On the one hand, we know that more violent crime is committed by low-income than middle- or upper-income populations. Where poor populations are concentrated in urban pockets, that’s where the crime is usually highest. On the other hand, general economic upturns – even those that improve the conditions and prospects of the poor – don’t necessarily reduce violent crime. Nor do economic downslides inevitably produce crime waves.

This disconnect between recessions or economic booms and violent crime has been true throughout American history, or at least since the late 19th century, when we started to have data with some degree of reliability. Consider major economic downturns. We suffered a massive recession beginning in 1893, a smaller decline in 1907, the Great Depression of the 1930s, and most recently, the Great Recession of late 2007 to 2009. In two of these economic catastrophes – which put millions out of work and brought hunger and misery to thousands – violent crime did not increase at all. In one, the devastating Depression of the 1930s, crime rose at first then declined after 1934, despite a further economic downturn in 1937. In the most recent recession, 2007-9, crime was falling dramatically, part of the post-1990s crime slide that may (or may not) have ended in 2015.

The depression of 1893 is one of the most striking illustrations of the discontinuity between economic conditions and violent crime. Not only did America’s urban population soar in the 1890s, but the living conditions within those cities were, by contemporary measures, Petri dishes for criminality.

The new urban masses were poor, often desperately so. They were densely packed into the most appalling housing, when not forced by impoverishment to sleep in public places or police station barracks. Urbanites below the middle class were unable to support their children past age 12, leading city youth to drop out of school to work long hours or join street gangs and steal for survival.

The cities were governed by thoroughly crooked municipal regimes, such as the notorious Tammany Hall in New York. The police, essentially a security force for the corrupt city governments, were untrained, incompetent and abusive – free with their nightsticks, especially in dealing with the “dangerous classes” of poor immigrants.

The immigrant groups (over 80% of New York City’s population was of foreign extraction in 1890), along with the African Americans who were just beginning their northward migration, were routinely discriminated against because of their nationality, their religion or their appearance, and were socially isolated from the city’s middle class, which fled to less menacing suburbs.

Despite these conditions, violent crime was relatively low. From 1890 to 1899 there were a total of 675 murders in New York City, which is less than there were in any one year in Gotham between 1970 and 1990. In 1970 alone there were 1,117 killings, and that was the best year of those two crime-infested decades. In the 1890s the city’s homicide victimization rate never exceeded 4 per 100,000. By contrast, from 1970 to 1985, New York City’s rate averaged 21.5 per 100,000.

Just as recessions don’t necessarily produce crime waves, economic booms don’t guarantee crime declines. The roaring 1920s also were a high-crime decade, with homicide victimization rates averaging nearly 9 per 100,000. Of course, this being Prohibition time, the booze gang wars helped keep crime rates high. Perhaps the best example of good economy/high crime was the 1960s. With vivid memories of riots, protests and bombings, it is sometimes forgotten that the economy of the 60s was supercharged. In fact, up to this period Americans probably never had it so good, financially speaking. Six of every 10 owned their own homes, eight of 10 a car. The work week declined to 40 hours while family purchasing power was up 30% over the previous decade. The unemployment rate averaged 4.8% for the full 10-year period and dropped to 3.5 in 1969.

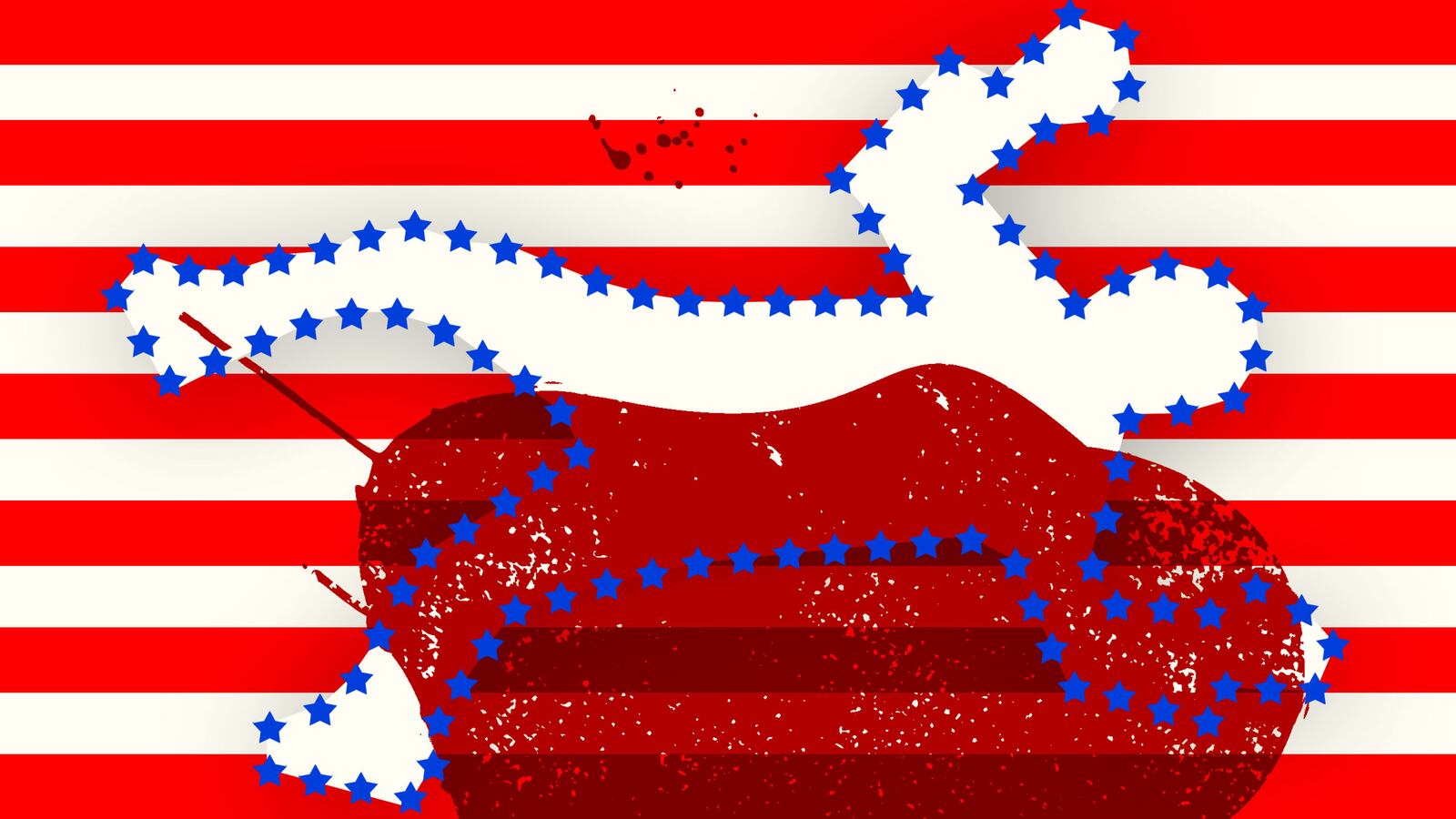

You know the rest of this story. Starting in the late 60s the United States suffered the biggest sustained rise in violent crime in over a century, perhaps the biggest in American history. More Americans were murdered between 1970 and 1995 – over one-half million – than died in all of the wars we fought from WW II on.

If economic conditions don’t explain violent crime, then what does? The first thing to remember is that violent crime is different. Acquisitive offenses, led by theft, are mainly motivated by economics. Larceny (nonviolent stealing) probably does increase when times are hard. If people become desperate for life’s necessities they will resort to stealing them. But violent crimes – murder, manslaughter, rape/sexual assault, robbery, and assault – are not usually motivated by money.

Murder, manslaughter and assault are mainly quarrel-based. Anger and disputes, abetted by alcohol and guns, fuel these crimes. Rape/sexual assault, obviously, has no economic motive either; it is driven by a craving for sexual satisfaction through force and violence. Robbery, defined as larceny by the threat or use of force, is a mixed crime, involving both economic motives and a desire to intimidate or hurt the victim. So robbery may or may not increase during recessions. It certainly increased in the post-60s era despite the positive economy.

It should be no surprise, then, that violent crimes are not correlated with general economic conditions. But what about the link between low income groups and violence noted at the beginning of this essay? How can that be explained?

The answer lies with the values of middle- and upper-class populations. They eschew violence and generally try to resolve disputes peacefully, using the law and courts if necessary. If they engage in crime it will be nonviolent high-end larceny and embezzlement. Contrast the young, unattached low-income male: what does he have to lose by fighting and killing? The true answer is “a lot,” but young men, being especially impulsive and heedless of consequences, i.e., lacking middle-class values, don’t think much about the future, not even their own.

So what are the policy implications of all this? Violent crime will diminish for low-income populations when they move up the social ladder. This happened with the 19th century Irish immigrants whose violent crime involvement was akin to the involvement of African Americans in the 20th and 21st centuries.

But who today talks about (or even knows about) Irish-American crime? That’s because the assimilation of the Irish – their movement into the middle class – removed them from the violent crime roster. It took two to three generations, but the Irish melted in. And I firmly believe that as we overcome our long, sad history of racism, the same thing will happen to African Americans.

Does this mean that raising groups to the middle class – as liberals have long advocated – is a type of crime control? In a sense, yes. So what policies will best achieve this? Here is where the ideological divide holds sway. The right’s priorities, as reflected in the Trump administration’s new tax proposal, for example, favors economic growth to expand wealth and employment – derided by the left as trickle-down economics. The left, meanwhile, pushes wealth redistribution policies, such as Medicare for all, to reduce the financial burdens on the poor. Whichever path we choose, we won’t know for a few more generations whether the policies we adopt now reduced the size of the poverty class and helped make violent crime a topic of mainly historical interest.