From Mark Twain publishing Grant’s memoirs to Nixon’s unapologetic account, it’s always controversial when a former president picks up a pen. But as Josh Robinson writes, few have stood the test of time.

Sitting at the Tehran Conference in 1943, as the United States, Great Britain, and the Soviet Union shored up their alliance, Winston Churchill already had plans to set down his wartime memoirs, once the whole grisly business was done. So it was with great confidence that he turned to Josef Stalin and Franklin Roosevelt with a promise. “History will judge us kindly,” he said in his growling baritone, “because I shall write the history.”

Gallery: The 20 Best-Selling Politicians

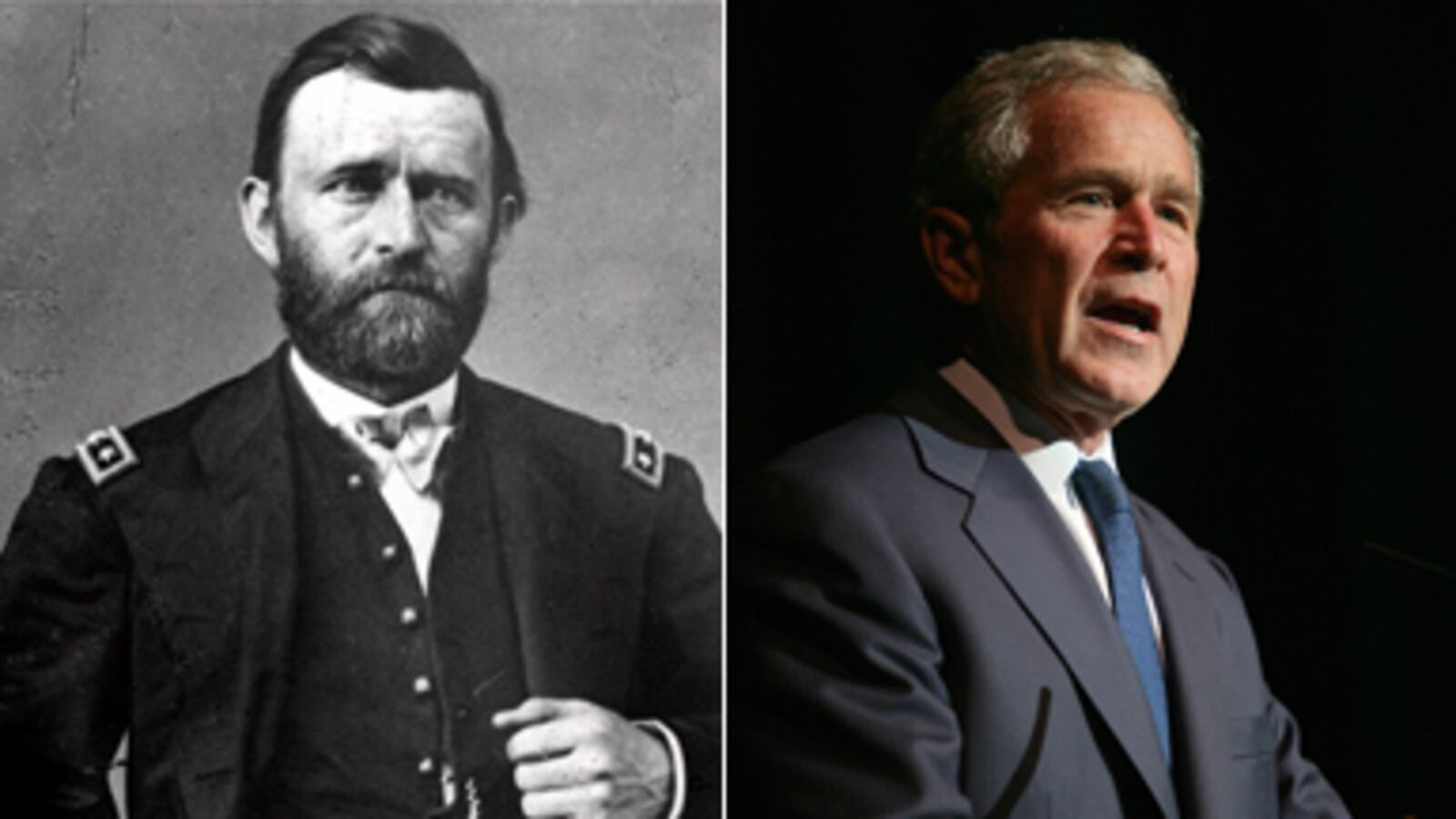

It is a lesson that men in power have taken to heart. None more so than the former presidents of the United States. And as George W. Bush’s memoirs, Decision Points, hit bookstores this week, he is joining a long line of ex-presidents who have—not always subtly—tried to guide the conversation about their legacies.

As a tool for historians, presidential autobiographies are usually much less valuable than personal papers or correspondence. By and large, they tend to be carefully choreographed retellings of political minutiae that serve to justify decisions. “Overwhelmingly, they are also boring,” said Ted Widmer, a historian at Brown University who helped Bill Clinton with preliminary work on his memoir, My Life. “I think that’s a given. The rare ones are the ones that step out of that and give you insight into private thoughts.”

The first memoir written by a former president to combine historical merit and real commercial success is considered to be Ulysses S. Grant’s. Though Grant is viewed as one of this nation’s lesser presidents, the Princeton historian Sean Wilentz said that his tainted legacy was largely the work of Southerners in the early 20th century. In fact, Grant was a hero in his own time, the savior of the Union, and in 1880, there had even been talk of running him for a third term.

But by the early 1880s, his popularity had not saved him from being nearly broke. So, perhaps sensing an opportunity, Grant’s close friend Mark Twain started a publishing firm, with his nephew in charge, specifically to publish Grant’s memoirs. Completed days before his death in 1885, they barely touched on the presidency, focusing instead on the Civil War. “He wanted to write about it authoritatively,” Wilentz said. “There were lots of records left from the war, but he wrote a very terse and elegant account of the war that he fought, from where he stood.”

It made Twain and Grant’s widow some real money. Then, the book was forgotten. It took two unlikely people to revive it half century later: Gertrude Stein and the literary critic Edmund Wilson.

After Grant’s, the next notable book by an ex-president was Theodore Roosevelt’s. Of course, Roosevelt had already written a bestseller before he won the White House with The Rough Riders, the bloody, action-packed story of his cavalry days during the Spanish-American war. His 1913 autobiography was not nearly as successful. But then again, the message of his memoirs did not have to be as delicately honed as Rough Riders’—he was not campaigning anymore.

“It’s not the best thing that he ever wrote, but it’s there,” Wilentz said. “Teddy left the presidency so popular, he didn’t have to settle many scores that way. It’s not like Bush. The Bush problem is that he had a very unpopular presidency, so everyone is waiting to see how he handles the things that made him so unpopular.”

Most of the men who followed Roosevelt in the White House went on to pen autobiographies after their terms—and sometimes several other books as well—but it seems that it did not become de rigueur until after World War II. Wilentz pointed out that it mirrored the tradition of presidents’ establishing libraries, so that historians could consult their personal papers. Every commander-in-chief since Franklin Roosevelt, with the exception of John F. Kennedy, has had both a library and a memoir.

More importantly, perhaps, the growth of the presidential memoir has gone hand in hand with “an enlargement of the presidency,” said Wilentz, who has written extensively about the office but most recently published Bob Dylan in America.

But why limit yourself to memoirs? The most prolific ex-president has, without a doubt, been Jimmy Carter, whom Wilentz called, “the graphomaniac of all time among former presidents.” Since leaving the Oval Office in 1981, he has written in excess of 15 books on pretty much everything, recovering quite well from his dull autobiography. There have been provocative arguments on how to handle the Middle East, nostalgic accounts of growing up in Plains, Georgia, poetry collections, inspirational religious titles, a novel ( The Hornet’s Nest) and even a children’s book called, The Little Baby Snoogle-Fleejer. Which is not something most people expected from him when he was struggling with stagflation.

“He did not have a successful presidency, so I think he prides himself on having turned in a performance which leads a lot of people to think of him as an exemplary ex-president,” Wilentz said. “He thinks of himself as a man of wisdom with much to contribute, who has been at the center of power, so why not?”

Richard Nixon handled his writing after the presidency much the same way. No children’s books, though. As a product of World War II and the Cold War, and a self-styled statesman of the world, Nixon felt he could offer valuable advice on foreign policy with books like No More Vietnams or Seize The Moment: America's Challenge in a One-Superpower World.

“That was his way back to respectability, writing cogent foreign-policy essays,” Widmer said. “That’s where he was at home. He loved to think strategy about the world.”

Nixon’s own 1978 autobiography, RN: The Memoirs of Richard Nixon, did not help his cause. Addressing one of the most shameful chapters in American history, he took a passive “Mistakes were made” approach. Because of the pardon, no one would ever be able to force him to own up to Watergate and, understandably, he chose not to. (Paying extra for one his special editions didn’t buy readers any more answers.) The book spurred a vicious backlash from groups like the Committee to Boycott Nixon’s Memoir. According to The New York Times, one of its founding members told a reporter, “Four years ago, he had a chance to tell the truth for free. Now he’s charging $19.95 a copy to tell us the same old story.”

His predecessor’s account of the presidency was equally unsatisfying. Lyndon Johnson, a man profoundly troubled by the impact of the Vietnam War on his term in office, wrote The Vantage Point to delve into the nitty-gritty of his decision-making process through the 1960s. It was the polar opposite, for instance, of Ronald Reagan’s An American Life, which served mostly to perpetuate Reagan’s mythical image, while conveniently ignoring things like Iran-Contra.

Different as the autobiographies that came out of the '50s, '60s, '70s, and '80s might have been in their content, the form remained fairly consistent. It took George H.W. Bush to reinvent it. In A World Transformed, he and former National Security Adviser Brent Scowcroft presented a discussion of the salient foreign-policy issues they dealt with between 1989 and 1991.

“It’s just a break from the old format of blow-by-blow ‘What I did, why I did it, and how I did it,’” Wilentz said. “It was a work of documentary history, funnily enough, as opposed to simply his autobiography.”

But the gold standard for presidential memoirs seems to be Clinton’s My Life, which offered insight into his presidency, a rich picture of his childhood, and a discussion of the Monica Lewinsky scandal. Clinton showed a keen understanding of how to treat his legacy early on in the writing process. Instead of hiring a ghostwriter, or seeking help from his inner circle of policy advisers, he reached out to Widmer, a historian and former speechwriter. Widmer’s job throughout the two or three years it took Clinton to write his book—which he did by himself, entirely in longhand—was to prompt him with questions, almost as if compiling an oral history. The result was a spoken draft before the first written draft, on the way to a 1,000-page tome that sold in excess of 1.6 million copies.

“I think he wanted to get right with history and tell a very full and honest story,” Widmer said.

The one to match Clinton’s might have been Kennedy’s, since he was already a Pulitzer Prize-winning author and inspired such fascination. Wilentz and Widmer agreed that history was probably cheated out of an exemplary presidential memoir. “ Profiles in Courage is beautifully written and genuinely interesting. So I think a rich presidential memoir would have been extraordinary from John F. Kennedy,” Widmer said, before joking, “It would have sold a billion copies.”

If his predecessors’ books are any indication, George W. Bush’s book probably won’t.

Plus: Check out Book Beast, for more news on hot titles and authors and excerpts from the latest books.

Joshua Robinson is a freelance writer based in Manhattan. His work has appeared in the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, the Washington Post, and Sports Illustrated.