The suicide of the shah’s son is the latest tragedy for a dynasty drenched in blood. Stephen Kinzer on the death of a prince. Plus, more on Prince Ali Reza Pahlavi's life.

Down the street from my apartment in Boston's South End, a single gunshot shattered the pre-dawn darkness Tuesday. Police arrived to find a suicide. This doesn't happen any more often in the South End than anywhere else, and passers-by like me were left to imagine what tragedy lay behind it. Then came news of the man's identity. He was Prince Ali Reza Pahlavi, son of the late shah of Iran.

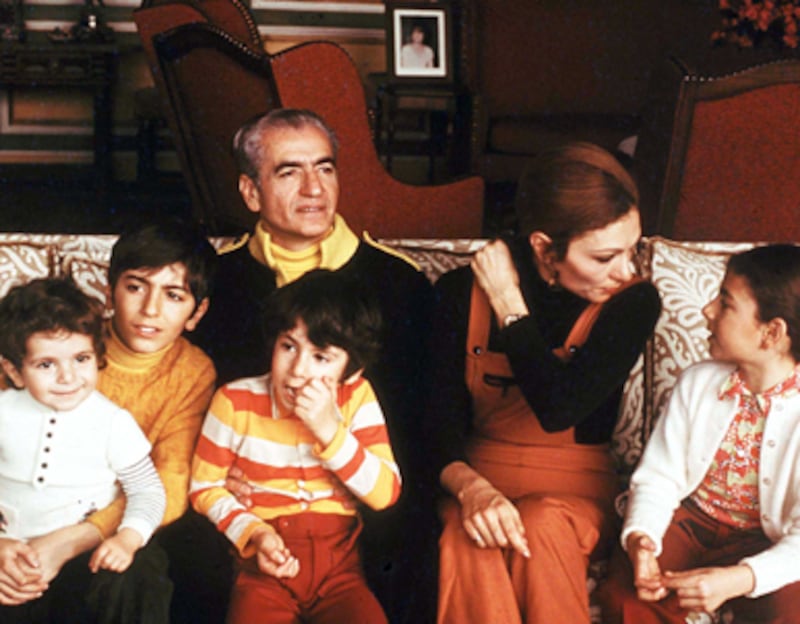

Gallery: Photos of the Iranian Royal Family

This shocking act of self-slaughter was the latest violent tragedy in the long history of a family drenched in blood—first that of the Iranians it tortured and killed, then its own. It is a drama of Shakespearean dimensions. The shah once ruled Iran with an iron fist, but his family later paid dearly for his sins, echoing Hamlet's judgment that royal crime “cannot come to good.”

Prince Ali Reza's father died in humiliating exile barely a year after being chased from his homeland in one of the 20th century's most spectacular revolutions. His aunt, Princess Ashraf, the shah's twin sister, a once-sinister figure known as Iran's “black panther,” has suffered through depressions and addictions, three failed marriages, and the assassination of one of her sons. His sister, Leila, was found dead in a London hotel room in 2001 after taking an overdose of barbiturates.

“Like millions of young Iranians, he too was deeply disturbed by all the ills fallen upon his beloved homeland, as well as carrying the burden of losing a father and a sister in his young life,” the Pahlavi family said in a brief statement on Tuesday. “Although he struggled for years to overcome his sorrow, he finally succumbed.”

Iran has also succumbed over the course of a cruel century, in large part because of the depredations of the Pahlavi dynasty. Yet this was a dynasty that set out to modernize and strengthen a nation that was prostrate and on the brink of extinction when it seized power. Prince Ali Reza's tragedy mirrored that of his long-suffering land.

The founder of the dynasty, Reza Shah, Prince Ali Reza's grandfather, was a titanic figure, a brutal tyrant but also a visionary reformer. He was an illiterate soldier who came to power in a coup and made himself shah in 1926. The main reason he refused to lead his country toward democracy was that he wished his son to be shah after he was gone.

That came to pass with Mohammad Reza Shah's ascension in 1941, but the son turned out to be a cowardly wimp, completely unlike his commanding father. He hated the democracy that emerged in Iran after World War II—personified by its most formidable leader, Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh—but could do nothing to crush it. Then, like a gift from God, the CIA and British MI-6 arrived to overthrow Mossadegh in 1953, angered by his attempt to nationalize Iran's oil industry. That allowed Mohammad Reza Shah to take absolute power.

The Pahlavi dynasty was one of the few facts of 20th-century geopolitical life that nearly everyone considered permanent and unalterable. Its collapse in 1979 stunned the world no less than the collapse of the Soviet Union a decade later.

He died in the manner of a soldier who cannot bear dishonor and disgrace, of a single shot to the head.

Prince Ali Reza spent his childhood in royal luxury. He was the second son of an absolute monarch who held the fate of 30 million people in his hands, became America's chief ally in the Middle East, and lost himself in such deep megalomania that he came to consider himself one of the greatest kings of all time, rightful successor to Persian titans like Cyrus, Darius and Xerxes.

The prince was not yet 13 when his family's world collapsed in 1979. Rarely in human history has a nation risen up so unanimously against a tyrant. Cataloging the Pahlavi dynasty's sins would be an exhausting task, but perhaps its greatest was driving Iranians to launch the revolution that brought brutal mullahs to power. Much as Prince Ali Reza detested their violently repressive regime, he cannot have failed to recognize the role his own family played in creating the conditions that allowed it to seize power.

He moved to the United States after his father's ignominious and lonely death in Egypt, attended prep school in the Berkshires, graduated from Princeton, and went on to study Middle Eastern and Persian history, as well as philology and ethnomusicology. He enrolled in a doctoral program at Harvard but did not complete it.

Once named as one of the world's most eligible bachelors, he was engaged to be married in 2001, but the engagement lasted for a reported eight years and then fell apart. His neighbors on West Newton Street say he never spoke to them; he would pull up in his Porsche, often wearing jeans and a nappy blazer, then disappear behind the walls of his brownstone, its bay windows permanently blocked by wooden shutters.

The prince's older brother, Crown Prince Reza, lives near Washington and periodically offers himself as a future shah of Iran. Prince Ali Reza never indulged in this fantasy, at least not in public, but he once said that bringing “freedom and democracy” to Iran was his “unique mission in life.”

Yet although some might say that fate has justly punished the Pahlavi family for its great crimes, the reality is that Prince Ali Reza was no more of a criminal than any of my other neighbors. If sons are guilty for their fathers' transgressions, he was surely covered with guilt, but if each individual is responsible for his own actions and nothing else, he was innocent. He never ordered an execution, dispatched anyone to a torture chamber, or prostrated himself before foreign power. He could honestly hold his head high. Yet the weight of his family history was evidently too heavy for him to bear.

One can only imagine the demons that tormented this exiled prince while he was cloistered in his darkened South End townhouse before taking his own life at the age of 44. He died in the manner of a soldier who cannot bear dishonor and disgrace, of a single shot to the head.

“Within the hollow crown that rounds the mortal temples of a king,” Shakespeare explained, “keeps death his court.”

Stephen Kinzer is an award-winning foreign correspondent. His new book is Reset: Iran, Turkey and America's Future.