American Jews were reminded once again last weekend that even in one of the safest countries in the world for Jews, they are never truly safe.

A gun-wielding man of British Muslim descent took four worshipers hostage in a synagogue in Colleyville, Texas. After hours of fruitless negotiations, the hostages fled for their lives and the gunman was subsequently killed by an FBI anti-terrorism unit.

As is often the case when high-profile antisemitic attacks occur, American Jews were bombarded by the now familiar “thoughts and prayers” from political leaders and media figures outraged by the latest manifestation of anti-Jewish hatred.

But such gestures are increasingly falling flat, particularly as more and more American Jews—and Jewish institutions—find themselves fearful and under assault.

Despite accounting for 2 percent of the US population, Jews are the victims in more than half of all hate crimes. One in four Jews say they have experienced antisemitism in the past year. Wearing a yarmulke in public is becoming an increasingly risky endeavor and an open invitation for ridicule or even assault. Synagogues today in America look more like armed garrisons than open and welcoming places of worship.

This is the new reality for American Jews. And if non-Jews want to truly stand with us, they need to do more than mouth empty platitudes.

For example, Republicans were quick to condemn the attack in Texas—and pledge their bona fides in fighting antisemitism—but where was their outrage when just last month former President Donald Trump said Jews used to have “absolute power” over Congress and that American Jews “either don’t like Israel or don’t care about Israel” because they overwhelmingly voted for Barack Obama and Joe Biden?

How many of them have spoken out against the routine and obscene use of Nazi atrocities committed against European Jews as an analogy to mask-wearing and vaccine mandates in the fight against COVID-19?

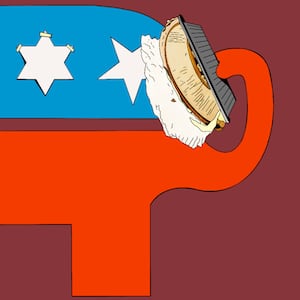

Truth be told, most American Jews don’t have the highest expectations for Republican politicians. The GOP has long used charges of antisemitism as a cudgel for dividing Democrats, all the while looking the other way at anti-Jewish animus in their own ranks.

But it’s the reaction on the left that’s more troubling for Jews, who have long viewed the Democratic Party and progressives as political and cultural allies. Progressives, by and large, are happy to talk about antisemitism when the culprit is a white right-winger. They are far more reticent when anti-Jewish hatred hits closer to home.

As the situation in Colleyville unfolded, some progressive commentators pointed a finger at white supremacists, which is not necessarily surprising. In 2017 neo-Nazis infamously marched in Charlottesville, Virginia, chanting “Jews will not replace us.” In 2018 a deranged gunman stormed the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh and killed 11 worshipers.

But antisemitism is more than just the oldest prejudice—it’s also bipartisan and multicultural.

Deeply liberal New York City is host to the majority of antisemitic assaults in the United States, and they are almost never carried out by white nationalists.

In 2018 and 2019, Orthodox Jews in New York were routinely the victims of antisemitic attacks, including slapping, kicking, sucker punches, death threats, menacing, vandalism, and swastika graffiti. According to the NYPD’s hate crime stats for 2019 and 2020, more than half of those arrested for anti-Jewish hate crimes were persons of color.

In 2019 two members of the extremist Black Israelite sect took over a Kosher supermarket in Jersey City and killed four people, including a local police detective. Weeks later, a machete-wielding Black man stormed a Hannukah celebration in Monsey, New York, killing one person. And then last May, Jews were attacked on the streets of Los Angeles, New York City, and a host of other major American cities by pro-Palestinian demonstrators. In Bal Harbour, Florida, four men surrounded a Jewish family and yelled “Die Jew” at a man in a yarmulke before threatening to rape his wife and daughter.

On college campuses, virulent criticism and demonization of Israel and its supporters is frequently lodged in the language of antisemitism and the ridicule and exclusion of Jewish students.

Media attention—and outcry from liberal commentators—has been far more muted after these incidents. At the very least, there’s been little introspection at the growing prevalence of antisemitism committed by non-white supremacists.

Few recent episodes have highlighted this resounding silence more than the reaction to comments by Rep. Ilhan Omar, who in February 2019 took to Twitter to declare that American support for Israel is “all about the Benjamins”—a long-standing conspiracy theory that claims Jews use their allegedly vast wealth to exercise influence and political power.

Though she half-heartedly apologized, only weeks later she obliquely suggested that American Jews maintain dual loyalty to the United States and Israel. She also argued that her comments are unfairly labeled as antisemitic because she is Muslim.

Many progressives rallied around the embattled congresswoman, all the while telling concerned American Jews that she meant no harm and that attacks against her were motivated by Islamophobia.

This is a recurrent phenomenon in the discourse on antisemitism.

American Jews are perhaps the only minority community in America who are regularly told by progressives that what they view as antisemitism really isn’t antisemitism. As the British comedian and writer David Baddiel notes in his book “Jews Don’t Count”:

“It is a progressive article of faith,” Baddiel notes, “that those who do not experience racism need to listen, to learn, to accept and not challenge, when others speak about their experiences. Except, it seems, when Jews do. Non-Jews, including progressive non-Jews, are still very happy to tell Jews whether or not the utterance about them was in fact racist.”

I was reminded of this odd circumstance in an exchange with the MSNBC anchor Mehdi Hasan. In the hours after the Colleyville incident he used his nightly newscast to express solidarity with the American Jewish community. “You are not alone. We have your back. And in this moment of fear, hate, and violence, you can count on the rest of us,” Hasan said.

Many Jews were rightly gratified by Hasan’s empathetic words. However, after I pointed out on Twitter that it’s not enough to simply express solidarity with Jews after high-profile incidents, Hasan directed me to an op-ed he’d written several years ago defending then-British Labor leader Jeremy Corbyn.

Corbyn had infamously made a host of antisemitic comments. He also associated with and defended virulent Jew-haters. But after British Jews published an open letter decrying Corbyn as an “existential” threat to Jewish life in the U.K., Hasan wrote, “Don’t. Be. Silly.” He added that it was possible to “commit to both defeating antisemitism and electing a Corbyn-led government.”

I don’t write to point fingers at Hasan—who is humane, fiercely honest, and whose heart is clearly in the right place. Rather, I offer up this admonition as a teachable moment.

Allyship means listening to American Jews when they point out antisemitism, not questioning what centuries of experience have taught us about anti-Jewish hatred. Having “our back” only some of the time is not enough.

Allyship also means looking inward at the ways that antisemitism has taken root and flourished in American society.

Indeed, the Texas hostage-taker took hostages in a synagogue because he believed that Jews exercise disproportionate power in the United States, and that by taking Jews captive his demands to free a convicted Islamic terrorist would be met.

It is an idea that is widely held across the political spectrum, from those who highlight the allegedly out-sized power of prominent philanthropists like George Soros to those who see financial suasion as the explanation for American support for Israel. Quite often, non-Jews use anti-Jewish tropes or speak in the language of antisemitism, not even understanding the prejudicial nature of their words. That’s why it’s so important to listen to Jews when they talk about the sometimes subtle nature of antisemitism—and the scars it leaves behind—just as we must listen to any minority community talk about prejudice.

The best possible response to anti-Jewish hatred is not just to speak up in the immediate aftermath of incidents like the one in Colleyville. That’s easy. The hard part is recognizing antisemitism when it occurs in its more benign, but common forms—and forcefully speaking out against it.

Frankly, Jews need to more forcefully demand such attention from their nominal progressive allies. Far too often we accept a few breadcrumbs of support rather than demanding more than just fancy words.

Quite simply, if you can speak out against Jews being held hostage in a synagogue but balk at condemning the routine use of antisemitic tropes by your political and cultural allies, then American Jews should not be in interested in ritualistic affirmations of support.

If you want to be true allies of American Jews, “thoughts and prayers” simply won’t do.