New York prosecutors appear to have found an opening they can exploit to pry open the notoriously insulated Trump Organization and get past its mob-like code of silence—by leveraging a long-running feud between two warring family fiefdoms.

It’s the company’s long-time chief financial officer and his son, Allen and Barry Weisselberg, versus the chief operating officer and his son, Matthew Calamari Sr. and Jr.

The target of this three-year criminal investigation has always seemed to be former President Donald Trump himself. To nail him, investigators might need to flip Allen Weisselberg, his right-hand finance man. But to get that guy, they’ll need to leverage his deputy, the accountant Jeffrey S. McConney. And it looks like they’ve found an avenue to pressure him: “Matty” Calamari Jr.

According to two people familiar with the matter, prosecutors are trying to use the Trump Organization’s young head of corporate security, Matty, to elicit damning information about the company’s controller, McConney. One of those sources said Matty’s only tie to McConney is that the accountant prepared his individual taxes years ago—and prosecutors are exploring whether those taxes accurately reported details about his residency and corporate apartment and vehicle.

Hence why “Matty Jr.” was subpoenaed to testify before the grand jury on Sept. 2. McConney was also brought in a second time later that same day, according to this person.

It’s gotten so apparent that, in multiple meetings and phone calls since the spring, Donald Trump has reminded business associates and other members of his inner orbit about the need for Trump Organization staff to “stick together” and stay strong, according to two other people familiar with the matter.

The twice-impeached former president’s point was simple: his staffers and confidants should not allow New York investigators to manipulate or play employees off one another over the course of the criminal probe into the Trump family empire.

Those calls for continued loyalty apply to the elder Weisselberg even as his name keeps getting stripped from Trump corporate documents since he was indicted this summer. (A recent email reviewed by The Daily Beast shows that he now goes by “senior advisor.”)

But prosecutors are counting on the ex-president’s calls for solidarity to fall on just enough deaf ears.

The enmity between the Weisselbergs and Calamaris dates back decades, and it centers on their unwavering love of Trump. Two longtime associates described a Shakespearean conflict of rival dynasties, with dukes competing for the king’s favor.

“They hate each other. It’s a war,” The Daily Beast was told last month by Jennifer Weisselberg, who is undergoing a contentious divorce with Barry Weisselberg and has become a witness for New York prosecutors.

If the latest gambit works, McConney could be a useful witness. For more than 30 years, McConney has reported directly to Allen Weisselberg—cutting checks, processing transactions, and implementing deals. Theoretically, the trusted company money man should have some knowledge about any possible financial crimes.

Until now, the odds of utilizing McConney seemed slim. He has a history of being a loyal company footsoldier who despises the political left and keeps his mouth shut. As The Daily Beast revealed in July, McConney protected higher-ups by taking the blame and chalking up potentially criminal behavior to mere accounting errors when the New York Attorney General’s Office interviewed him for its previous investigation of the Trump Foundation. And it’s unclear if McConney was helpful at all to the prosecution when he appeared before the grand jury on this investigation in the spring.

But any damning information from Matty could change that equation.

This has not gone unnoticed. In the upper echelon of Trump’s business and personal circles, it started becoming more common knowledge—as well as a topic of concern and irritation—this summer that prosecutors have been trying to use multiple Trump-linked families against each other, people with knowledge of the situation said.

These families have each had multiple respective members employed by Trump, and each family includes fathers who have pledged professional, personal, or even political devotion to The Donald and his kin.

The offices of the Manhattan district attorney and the New York state attorney, which are jointly working on this case, declined to comment. Spokespeople for the Trump Organization and the former president did not respond to requests for comment on this story.

McConney and his attorney, Patricia Pileggi, did not provide statements for this story. Neither did Allen Weisselberg and his attorneys, Brian C. Skarlatos and Mary E. Mulligan. The Calamaris and their attorney, Nicholas A. Gravante Jr., also declined to comment.

As a feature and not a bug, the Trump Organization is rife with nepotism. The general public is already familiar with how Trump placed his daughter and two sons in positions of leadership, before and during his government administration. It’s less widely known, however, that Allen Weisselberg’s son, Barry, has managed the company’s Wollman ice rink in Central Park for years—or that COO Matthew Calamari’s son, Matt Jr., is the head of corporate security.

Allen Weisselberg is a holdover from the days of Donald Trump’s father, Fred. Just a few years after graduating college, Allen started as an accountant in Brooklyn at the father’s real estate business in 1973. He eventually transitioned to the son’s emerging empire in 1986 and became Donald Trump’s company controller.

Weisselberg stuck around through bitter bankruptcies and flopping business projects, with McConney under his supervision as a lower-ranking accountant, according to associates. When Weisselberg rose to the position of chief financial officer at the Trump Organization, McConney took over his old role as company controller.

Weisselberg’s financial acumen and personal loyalty to the Trump family made him the don’s right-hand man. While Trump would dream up deals, Weisselberg would secure the financing, and McConney would implement his boss’s plan. Weisselberg always had the final say when it came to structuring employee compensation, two sources said. And it was he who would sit in a private room with Trump himself each year and develop what they considered the appropriate monetary values for their vast real estate portfolio—and what they should pay accordingly in taxes, according to one source familiar with the annual ritual.

It’s no surprise, then, that when Trump became president and was forced to step away from the day-to-day of his business empire, he put Weisselberg—alongside Eric Trump and Donald Trump Jr.—in charge of the trust that owned and controlled the organization and the then-president’s assets.

Along the way, Weisselberg brought his own family into the mix. His son Barry became the manager of Trump’s ice rink in Central Park. His other son, Jack, did not join the Trump Organization outright but still operated on the periphery as a director at Ladder Capital Corp., which has made several loans to the company.

Meanwhile, Matthew Calamari Sr. took a similar but slightly different track into Trump’s inner circle. He got started as Trump’s hired muscle. Barbara A. Res, an engineer who led construction projects for the company in the 1980s, told The Daily Beast that she still recalls how Calamari got his toe in the door.

Trump noticed him while attending the 1981 U.S. Open semifinal tennis tournament over a weekend in New York City, where Calamari was the security guard who aggressively pounced on two young men and dispatched them posthaste. Trump was so impressed that on Monday morning he called Res, who was overseeing construction of Trump Tower, and told her: “I got this guy… we’ll put him in charge of security!”

She cautioned against that and suggested he hire a company instead. But Trump would not be convinced. Calamari, fresh out of college where he’d played football, was tasked with protecting the building as it was being constructed.

“A lot of people didn’t like him,” Res said. “He was forceful, menacing, intimidating. He was bigger than he is now… I thought he was sort of spying on everybody.”

When Trump Tower was finished, Calamari became the head of security there. And he was eventually elevated to be Trump’s personal guard. Several sources who’ve flown in and out of Trump’s orbit over the decades told The Daily Beast that the real estate mogul made him a bodyguard and occasional chauffeur, mostly because he looked and sounded the part of a typical, New York labor union tough guy—or, at least, the caricature of a tough guy who appeared in Trump’s mind.

Throughout Calamari’s many years in which he dedicated his life to serving the House of Trump, the famous, tabloid-dominating businessman liked having Calamari physically around him as a blunt instrument of sorts, sources told The Daily Beast. Trump believed Calamari helped convey an air of intimidation and ruthlessness, those sources recounted.

One person with direct knowledge of the matter, who described Trump as having “fetishized” Calamari’s appearance and persona, said they had been around on multiple occasions when Trump would point to or mention Calamari and then joke to people around him that Calamari “will kick your ass, watch out,” or that he could “kill you” very quickly.

By 1992, Calamari was vice president of corporate security, tasked not only with protecting Trump’s property, but also spearheading the internal investigation that caught the guy who broke into the apartment of Trump’s lover, Marla Maples—who would later became his wife.

Calamari, as Newsday described it then, “got [the man] to voluntarily submit to a search of his Manhattan office.” In 1995, when an employee claimed to have found evidence of “financial improprieties” and sent his wife and child to pick up documents at the office, Calamari and his security team stopped them—and allegedly trapped them, according to a lawsuit that went nowhere.

By the time Calamari made a brief appearance on The Apprentice in 2004—in which he froze and remained unable to form complete thoughts—he had shot up to chief operating officer, overseeing improvement projects.

Like Weisselberg, Calamari brought his son into the fold. Matty’s online resume says he worked security at the company while attending college, only to follow in his father’s footsteps and rise to head of corporate security in 2017.

Long-time associates said that while the Weisselbergs and Calamaris compete to curry favor with The Donald, they also feel that each is entitled to the benefits the other has received.

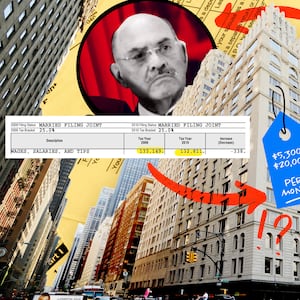

For example, Trump in 2004 gifted Barry and Jennifer Weisselberg a luxury apartment at 100 Central Park South—one Manhattan’s most desirable locations because it faces the biggest stretch of green in the city. Years later, Matthew Calamari Sr. asked Trump why his son shouldn’t get the same, according to a person with knowledge of the interaction. Calamari Jr. eventually got a corporate apartment at the same building, according to two associates and a neighbor.

And while Allen Weisselberg got a corporate apartment in a building that faces the Hudson River and the New Jersey skyline, Matthew Calamari Sr. was given a high-end corporate apartment at the Trump Park Avenue building four blocks away from Trump Tower, according to two associates and two neighbors.

But this tit-for-tat now exposes the Calamaris to a possible attack from prosecutors.

The June 30 indictment against Allen Weisselberg—the only individual charged with crimes so far—alleges that he received valuable benefits in the form of apartments and cars that weren’t taxed the way additional salary would be. The charging document lists his apartment at Riverside Boulevard, his son’s former place bordering Central Park, and two Mercedes vehicles.

The Calamaris, meanwhile, are expected to defend their freebies by arguing that their jobs necessitate being a short stroll away from the company headquarters. After all, they both deal with security issues that range from midnight emergencies and random calls from the police and fire departments—particularly since the company founder became one of the most hated men in the world.

In New York, people who provide secret testimony before a grand jury are offered immunity for what they disclose, so McConney and the younger Calamari might be in the clear. Although, prosecutors could still pursue perjury charges against either of them for lying.

But the elder Calamari and younger Weisselberg are widely considered to be on the shortlist of Trump Org executives who could be indicted next for getting untaxed perks—and further law enforcement action appears to be coming.

At a court appearance on Monday, Allen Weisselberg’s attorney revealed that investigators have discovered a tranche of evidence in the basement of an unnamed co-conspirator. That attorney, Skarlatos, added that he has “strong reason to believe there could be other indictments coming.”

—with additional reporting by Lachlan Cartwright