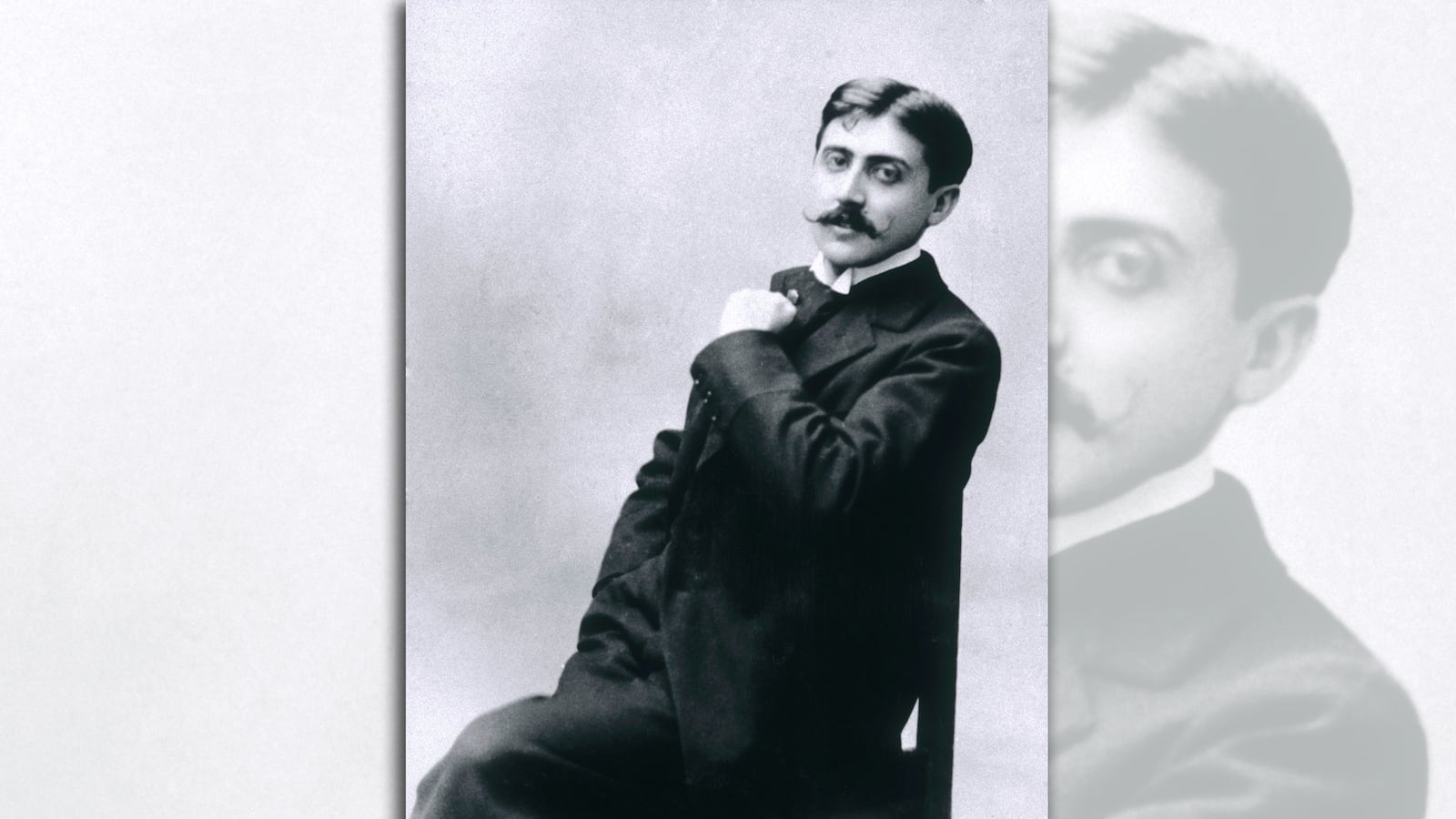

Marcel Proust (1871-1922), of hallucinogenic tea-cake fame, has become the unlikely pinup of the moment, thanks in part to the 100th anniversary of the publication of Swann’s Way, the first tome of his monumental Remembrance of Things Past, or, if you prefer, In Search of Lost Time. Recent years have seen Proust reading groups, websites, blogs, tee-shirts, wristwatches, films, plays; coffee-table books featuring Proust’s taste in painting or recipes for dishes mentioned by Proust, endless biographies, books about the author’s overcoat or his library, and numerous guides to reading his enormous novel, as well as memoirs of having read it. There has been both a doggedly literal French comic-book version of parts of the novel and a freestyle Japanese manga adaptation of the entire thing, with almost no dialogue. Proust has been recycled as a self-help guru and a neuroscientist, and shared billing with a squid (and, I would be tempted to add, with especially searing derision, there has even been a book about his alleged lesbianism, were I not myself the author of the slim volume in question). The current year will have seen an unprecedented number of Proust lectures, Proust readings, Proust conferences (sorry, guilty here too), Proust volumes, Proust knickknacks, Proust refrigerator magnets. And for some time now Proust has provided the punch-line for any number of New Yorker cartoons, always featuring either petites madeleines or high-culture long-term reading goals never achieved, or both.

In short, Proust has somehow become at once an inaccessibly highbrow exemplar of unreadable literary fanciness—Proust longus, vita brevis, as one early 20th-century wag put it—and a pop-culture icon, never without his emblematic madeleine and cup of limeleaf tea. If the author of a plotless 3,000-page novel composed of reader-defyingly long, syntactically complicated sentences about the nature of Time and Memory and Art, combining lengthy expository passages with confusing narrative, can come to adorn tee-shirts and watch-faces, something peculiar must be going on. The problem with Proust’s novel is that on the one hand it lends itself to synoptic profundity, since everyone has experienced “Proustian moments” in which one smells a smell, or tastes a taste, which evokes childhood sensation with disarming immediacy, while on the other hand, if this were really the main point, there would have been no need for those 3,000 pages; a short essay would have sufficed.

Proust was himself, to a great extent, responsible for this. For one thing, his Recherche du temps perdu was at its origin the product of a hesitation on the author’s part between the essay and the novel format. He wanted, in other words, both to instruct and to divert, and when he felt that he’d finally found his hybrid medium, in 1908—some five years before he managed to persuade a publisher to take on the project—he announced to a friend that he’d just begun, and finished, a very long book. This meant that he’d written the first part of the first volume and the last part of the final one. He spent the entire rest of his life filling in the rest. Unfortunately, what the world most often retains is precisely what he was prematurely talking about in 1908: the very beginning, with its madeleine and cup of tea, and the very end, with its reiterations of the opening section’s insights and promise of redemption via the work of art.

The bad news is that Proust’s novel is indeed very, very long, and that many of its sentences are also very, very long, and sometimes hard to follow, and that there’s not much of a plot, and there are a lot of characters, and that it’s hard to keep track of them all, and that he likes to engage in anticipatory retrospection, along the lines of “this moment was, for reasons that I will eventually reveal, to play a major role in my life,” and that the reader may confidently expect to slog, or sashay, or possibly zoom, through several hundred pages at least before learning exactly why that moment was to prove so important in the life of the semi-autobiographical protagonist. The good news is that what lies between the madeleine and the promise of redemption via the work of art itself is the best part.

Proust is, in addition to everything else, very funny; much funnier, in fact, than all those New Yorker cartoons. This is not often noticed, because of his exalted place in the literary pantheon, somewhere between Dante and Joyce (both whom can also be quite funny, but this too tends to be a well-kept secret). We take our cultural icons very seriously, often to both their detriment and ours. The key to almost everything in Proust, for instance, is Groucho Marx’s line that he wouldn’t want to belong to a club that would have him as a member. Everyone in the novel is always trying to get into clubs that won’t have them as members; this basic principle explains all the love-relationships in Proust’s world, as well as all the social machinations. The only club to which the narrator wants to gain access and that may eventually agree to let him in is that of Art, which can’t happen until after the novel’s conclusion, and indeed didn’t happen until after the author’s death. Proust’s novel is among many other things surely the world’s most fully documented case of writer’s block, and for this, if for nothing else, it deserves our interest in itself as well as because of its author’s life as a giant squid.

The Proust Reread Conference will run on October 4 and 5 at Columbia University. It is open to the public. More information, here.