One of best novels of 2011 was Amy Waldman’s The Submission, about a jury unwittingly choosing the design of a Muslim architect for a 9/11-like memorial. The uproar over the award consumes the whole country, feeding a frenzied media and hungry politicians. Everyone wants his or her say.

Now life is imitating art, with a controversy erupting over this year’s Pulitzer Prize for Fiction. On Monday, the prize committee announced that it had not chosen a winner for the fiction award for the first time since 1977. Publishers are fuming, The New York Times said, presumably because no prize means no Pulitzer sales bump. “BREAKING: Fox News Wins Pulitzer for Fiction,” the comedian Andy Borowitz quipped, as readers and pundits around the world took to Twitter to vent their outrage. "Perhaps it is the end of the world," MTV Books tweeted.

Maureen Corrigan, one of three jurors for the fiction prize, said she was just as shocked as everyone else when she learned Monday that there would be no fiction winner. “Honestly, I feel angry on behalf of three great American novels,” said Corrigan, a critic in residence at Georgetown University and a book critic for NPR’s Fresh Air.

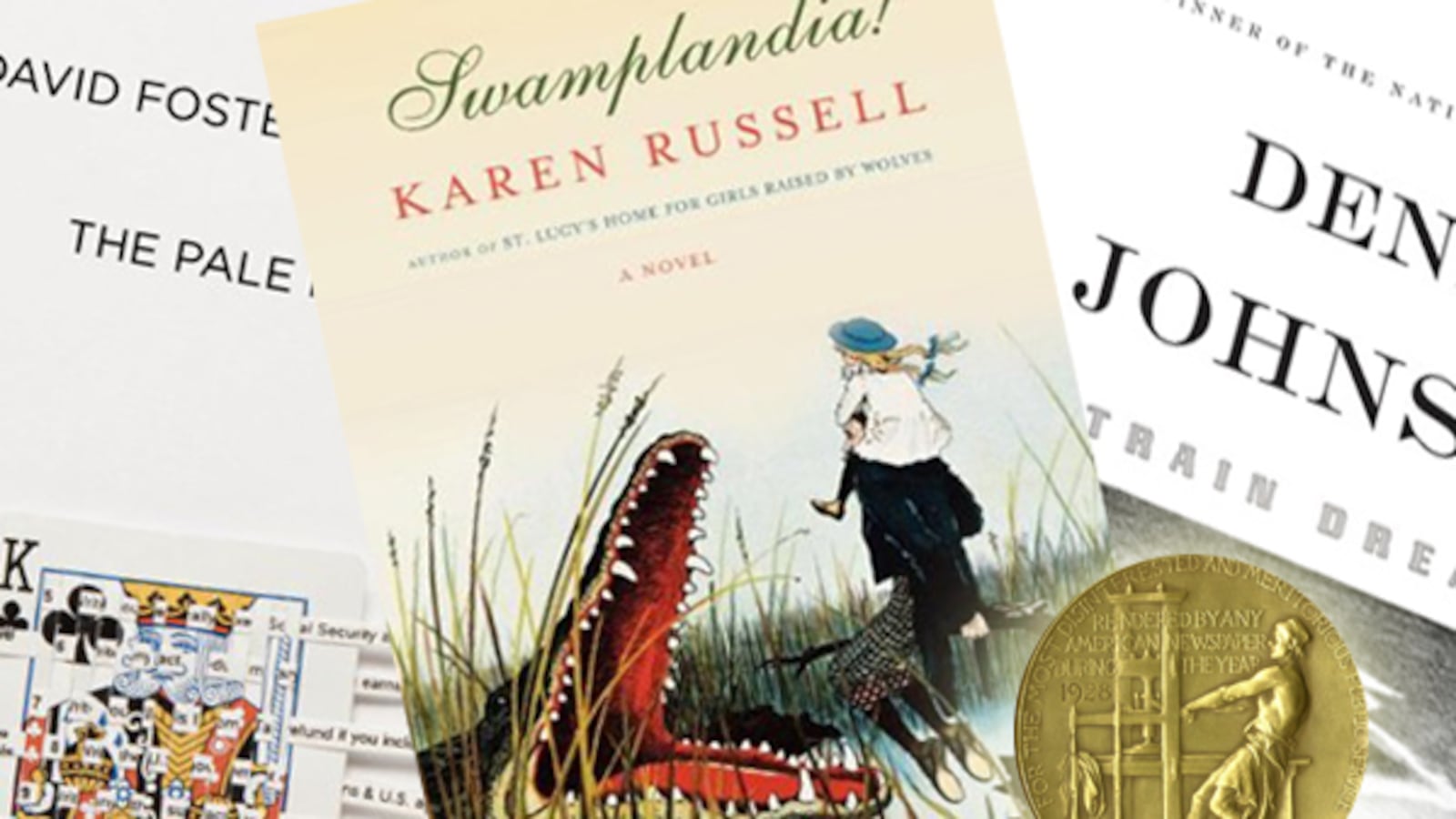

Corrigan, along with Susan Larson, former books editor of The Times-Picayune and host of The Reading Life on WWNO-FM, and Michael Cunningham, author of the 1999 Pulitzer winner The Hours, read about 300 novels each over the course of six months. They then met and corresponded to pick the required three finalists: the late David Foster Wallace’s posthumous and unfinished The Pale King, which was pieced together from manuscripts by Wallace’s editor, Michael Pietsch; the young Karen Russell’s quaintly surreal debut Swamplandia!; and Denis Johnson’s stark and spare novella Train Dreams. The three were submitted to the Pulitzer Prize board, made up of 20 journalists and academics, 18 of them voting members, who must come to a majority vote on the winner. Or not, as was the case this year.

Corrigan, Larson, and Cunningham realized that all their hard work had come to naught. Even worse, the null-decision gave the impression that they must have believed no fiction book was worthy of the prize this year. ("This year, nobody was good enough," wrote the Huffington Post.)

"I can safely say that anger and surprise/shock, and just sort of feeling this is an inexplicable decision on the part of the board—that really characterizes, I think, the way all three of us feel," Corrigan said. She had never thought about wanting the rules changed—until now.

"The obvious answer is to let the [jury] pick. We’re the people who have gone through the 300 novels. All the board is asked to do is to read three top novels that we’ve given to them…In fact, what’s happened today is a lot of the articles and blog posts have gotten it wrong—they’ve been blaming the three of us!"

UPDATED: Cunningham also agreed that the board should think about revising the selection process. “I think there's something amiss in a system where three books this good are presented and there's not a prize,” he said. “So, yeah, they might want to look into that.”

Sig Gissler, the administrator of the Pulitzer Prizes, said, “It’s unusual for the fiction award to be a problem, but it was a problem this year. It’s not unheard of, but it’s unusual.” Indeed, it’s happened 11 times, the last in 1977. Back then, the jury presented three finalists along with recommending one winner. In 1977, the suggestion was A River Runs Through It by Norman Maclean, but the board decided not to give the award.

In 1984, the board overruled the jury’s recommendation to award the prize to Thomas Berger’s The Feud, instead choosing William Kennedy’s Ironweed. "It’s happened 15 times in drama!" Gissler said. "There’s always going to be dissatisfaction, frustration. But [this year] the board deliberated in good faith to reach a decision—just no book got the majority vote."

The Pulitzer board is strictly forbidden to talk about the closed-door proceedings, and Gissler was being unusually candid when he said there was a “problem.” With that gag order in place, the reason behind the decision will remain unclear.

"They could have been passionate admirers of all three books," said Harold Augenbraum, executive director of The National Book Foundation, which administers another of America’s major book prizes, The National Book Awards. "And because the Pulitzer board has to vote in a majority, and so if you have 18 members, if you’ve got seven, seven, and four, that means that there’s not going to be a prize. It doesn’t necessarily mean they didn’t think one of the books was worthy."

The National Book Award for Fiction is chosen by five writers. The National Book Critics Circle Award is picked by 24 book reviewers who serve three-year terms. Three judges select the annual PEN/Faulkner Award. Augenbraum believes the diversity of the four major American literary prizes is a good thing. "They all have different personalities," he said. They result in different winners, and generate a wider and more passionate conversation about what good literature is, and how it manifests itself so that an audience can recognize it.

Both Corrigan and Augenbraum said they thought 2011 was a strong year in fiction. Wallace’s Pale King goes deep into what it means to be bored and a working stiff in America. Swamplandia! introduces an audaciously original American wry voice in Russell. And Johnson is a master of the pared-down archetype; despite the length of Train Dreams, its silence and space occupy a vast wasteland.

Then there’s Waldman’s visionary and prescient political indictment. Trusted commodities Jeffrey Eugenides and Russell Banks produced major psychological works (The Marriage Plot and Lost Memory of Skin), audacious young minds like Teju Cole and first-time novelists Chad Harbach and Tea Obrecht wowed critics and gained followers (Open City, The Art of Fielding and The Tiger’s Wife), and admired female authors like Ann Patchett and Dana Spiotta took over the spotlight (State of Wonder, Stone Arabia).

"We’re getting some suggestion from some of these articles that maybe we were scraping around, desperately trying to find novels, but that was not the case," Corrigan said. She has decided to never again be on the jury. "Only if the rules were changed."