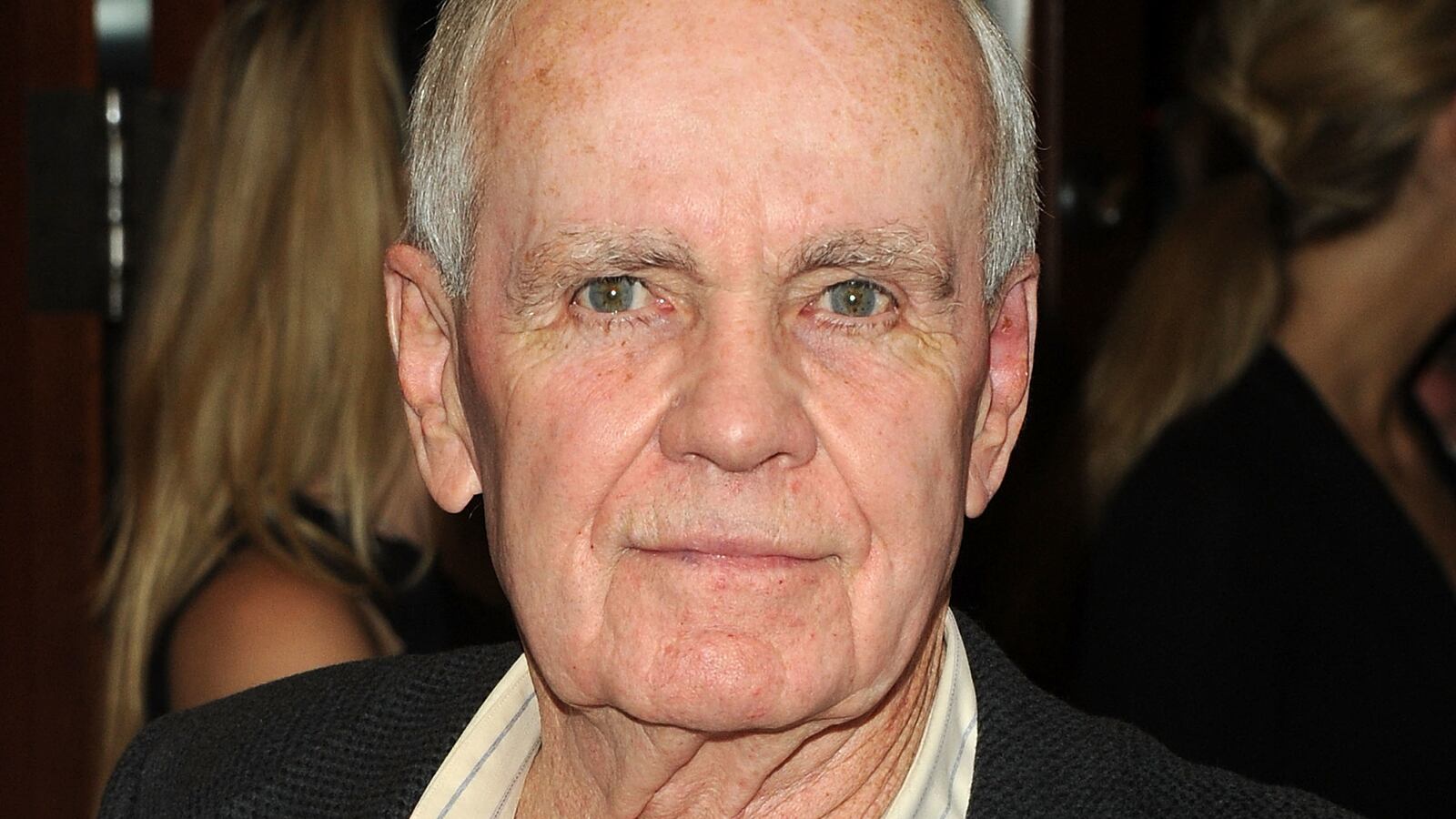

Cormac McCarthy, the Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist widely regarded as one of the greatest American writers of all time, died Tuesday at his New Mexico home, his publisher announced. He was 89.

McCarthy’s death was confirmed by his son, John McCarthy. A specific cause of death was not immediately shared, but his publisher, Knopf, attributed it to natural causes.

The McCarthy canon consisted of 12 novels, two plays, five screenplays, and a handful of short stories. His stylistic bleakness—both in content and form, with the writer favoring apocalyptic backdrops, gruff protagonists, and aberrant punctuation—was instantly recognizable. He hated the “idiocy” of semicolons, and his dialogue lived on the page unburdened by quotation marks or character attribution.

“Simple, declarative sentences,” he once said. “I believe in periods, capitals and the occasional comma. That’s it.”

Death and violence suffused his work, something he was almost always asked about when he granted rare interviews.

“There’s no such thing as life without bloodshed,” he told The New York Times Magazine in 1992. “I think the notion that the species can be improved in some way, that everyone could live in harmony, is a really dangerous idea... Your desire that it be that way will enslave you and make your life vacuous.”

He largely shunned the spotlight, shocking those who knew him when he agreed to his first and only on-camera interview with Oprah Winfrey in 2007. He seemed to prefer the company of scientists and researchers, and spent decades as an informal artist-in-residence at New Mexico’s Sante Fe Institute.

“There isn’t any place like the Santa Fe Institute, and there isn’t any writer like Cormac, so the two fit quite well together,” Murray Gell-Mann, a friend and one of the institute’s founders, explained to Vanity Fair in 2005.

McCarthy and Gell-Mann met in 1981, the same year the writer won a MacArthur “genius” grant. At the time, he’d been living in a motel, according to the Times. Even after winning the grant, he continued cutting his own hair, eating his meals off a hot plate, and washing his clothes at the laundromat.

His haunting of the institute was particularly notable given that McCarthy never graduated from college, abandoning a physics and engineering degree at the University of Tennessee to join the U.S. Air Force in 1953. There, he later claimed, he picked up a voracious reading habit.

“I read a lot of books very quickly” to kill time in Alaska, where he was stationed for much of his four-year stint in the Air Force, he told the Times. He went down south to give university another shot; when it didn’t stick, he turned to writing, and published his first novel, The Orchard Keeper, in 1965.

McCarthy penned approachable bestsellers like All the Pretty Horses, his sixth book and 1992 breakout hit; gruesome anti-Westerns like Blood Meridian, his savage 1985 masterpiece that features dead babies hanging from trees and necklaces made of human ears; and searing fables like The Road, which was awarded the 2007 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction.

Clocking in at a characteristically lean 287 pages, The Road depicts a father and son trudging through a world devoid of color and hope, past interstates where “long lines of charred and rusting cars” are “sitting in a stiff gray sludge of melted rubber” and shorelines where “the ribs of fishes in their millions [stretch] along the shore as far as eye could see like an isocline of death.”

The novel’s desolate vision, which was greeted with instant commercial and critical success, was adapted into a movie starring Viggo Mortensen just three years after its publication. (All the Pretty Horses got the film treatment in 2000, with director Billy Bob Thornton tapping Matt Damon and Penélope Cruz to star.)

The best-known and most beloved adaptation of his work, however, remains 2007’s No County for Old Men, a cinematic juggernaut that cleaned up at that year’s Academy Awards, netting Joel and Ethan Coen gold statues for directing, adapted screenplay, and best picture. Actor Javier Bardem also won best supporting actor for his chilling depiction of Anton Chigurh, McCarthy’s dead-eyed and psychopathic hitman.

After decades of stalling out, it was reported in April that a film version of Blood Meridian would be brought to the silver screen by John Hillcoat, the director of The Road. McCarthy and his son were said to be attached as executive producers.

The announcement raised more than a few eyebrows among McCarthy’s acolytes, who know better than anybody of the book’s reputation as a supposedly unfilmmable tome.

Asked by The Wall Street Journal in 2009 about that reputation, McCarthy replied, “That’s all crap.”

“The fact that it’s a bleak and bloody story has nothing to do with whether or not you can put it on the screen,” he continued. “That’s not the issue. The issue is it would be very difficult to do and would require someone with a bountiful imagination and a lot of balls.”

“But the payoff could be extraordinary.”