Japanese whisky fans know the story of Masataka Taketsuru, the man who traveled from Japan to Scotland a century ago and spent two years learning how the Scots made whisky. He then returned to Japan with his newfound knowledge and went on to change the trajectory of what had been a humble and low-key distilling industry. Taketsuru played a key role in the launch of Suntory and then created his own brand, Nikka.

So it’s with a small bit of irony that a 100 years later, a Scotsman has come to Japan with the intent of unsettling an industry and “pushing the boundaries of the Japanese whisky category.”

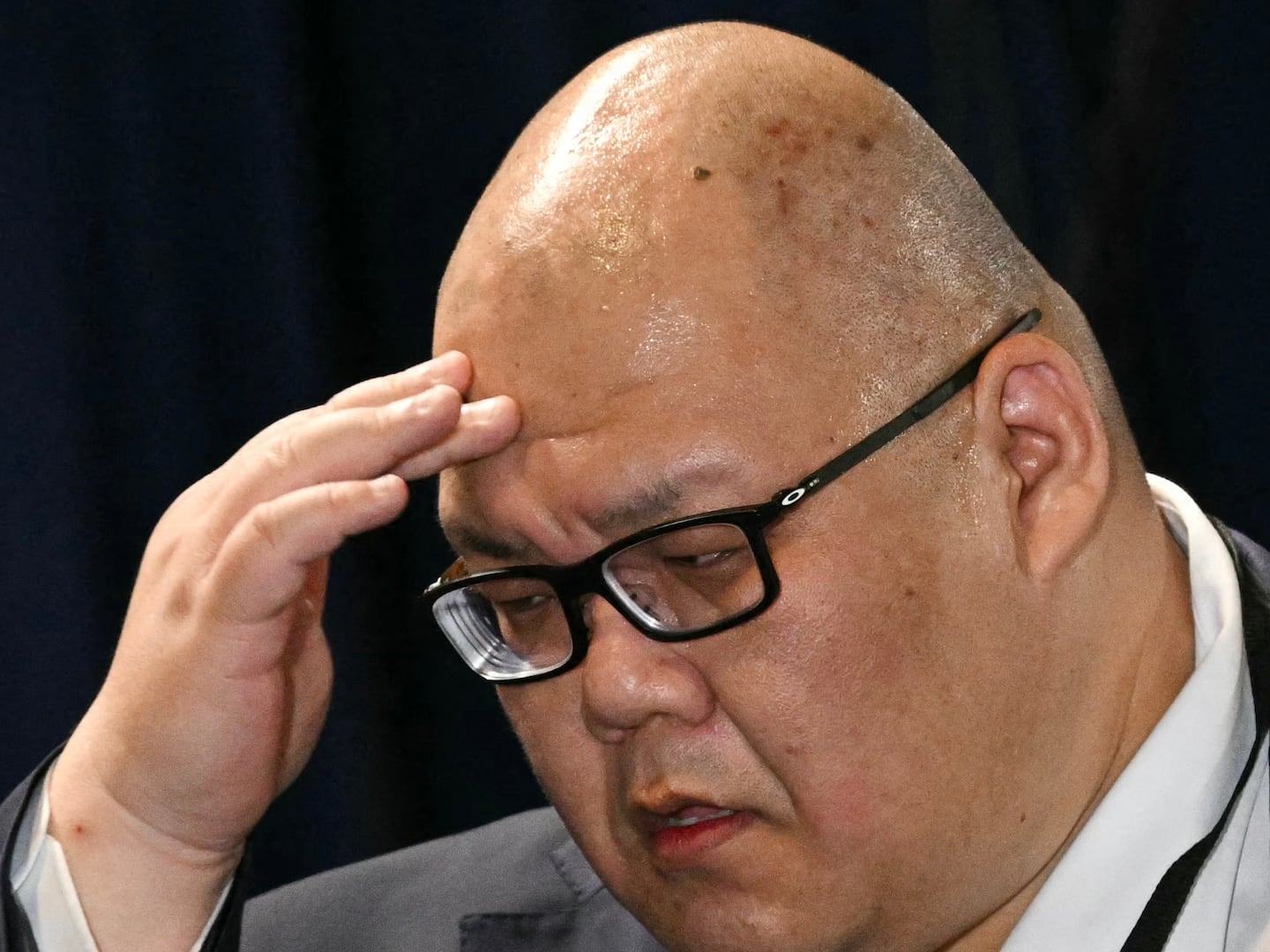

Nicholas Pollacchi is a partner and head of global whisky at IND Beverages, a small beverage firm launched by sisters Lauren and Rachel Simmons. They recently released Shibui, a line of whiskies sourced from lesser-known Japanese distilleries. (The name translates roughly as “understated cool.”) IND Beverages led off with nine expressions made by four distilleries, including a “world whisky blend” and a line of traditional rice whiskies. The goal? Release two or three new bottlings each year.

The idea of a Japanese “world blend” has gotten something of a black eye in recent years. As Japanese whisky was discovered by the thirsty American whiskey market, it edged into cult status. Supplies dwindled, prices rose and chaos ensued. The problem is that Japan had very loose liquor labeling regulations and those with a scruple deficiency would import aged whiskey from abroad, blend it with a small measure of Japanese distillate, and market it as Japanese whisky. Consumers would then buy what’s essentially a mid-range Scotch lightly flavored with Japanese whisky but priced as a cult-liquor premium product.

Such marketing was actually allowed under Japanese rules, which defined Japanese whisky simply as whisky that had been bottled in the country. Faced with rising concern about sketchy Potemkin whiskey, the trade group that oversees labeling, the Japan Spirits & Liqueurs Makers Association, changed regulations in the spring of 2021 to prohibit whiskey from abroad claiming to be “Japanese whisky.” Bottlers can’t even use misleading imagery on its label such as a Japanese flag or kanji characters. But the new regs won’t be fully enforced until 2024,

After that Japanese whisky must be entirely produced within Japan.

Pollacchi has no problem with the new regulations that require blends to drop the pretense. “I think that’s half the battle with Japanese whisky,” he says. “There’s an element of distrust. Because there’s a lot of crap out there.” The company insists on transparency, which is baked into its slogan: “We don’t distill, we discover.”

After all, Pollacchi notes, Scotland’s spirits industry was in large part built on the hallowed art of blending. Producers would acquire different styles of whiskies sourced from distilleries around the islands—some Lowland, some Highland, a touch of smoke from Islay—to create an array of distinctive bottlings.

Shibui’s Nigata range features lowland Scotch blended with whisky from a distillery in the Nigata prefecture, about four hours north of Tokyo. The releases include a grain whisky, along with two pure malts, one with no age statement and a second one aged 10 years. (Retail prices run from $50 to $140.)

To offset the distrust that’s recently afflicted Japanese whisky, Shibui is making its sourcing plain for all to see. In that, they’re following the route pioneered by Compass Box in Scotland, which has ruffled some feathers by shining a light on its sourcing practices. This is in stark contrast to the Scotch industry that doesn’t generally allow the component whiskies of a blend to be named. “That’s exactly what we’re trying to do,” Pollacchi says. “We’re adamant that they [the distillers] be the focus of the story. We’re trying to open up the market, one in which a lot of questions arise about provenance of the spirit.”

The Okinawa range of single-grain Shibui whiskies also emphasizes transparency but highlights traditional rice whiskies. “We’re dealing with seventh-generation, family-owned distilleries, going back to the 19th century,” Pollacchi says. Why would they want to hide that from American consumers?

The Okinawa range includes six rice whiskies sourced from three distilleries—Shinzato, Shunzo, Kumensen—in Okinawa, Japan’s southernmost prefecture. These whiskies are made using traditional black koji, a source of fungal enzymes that break down the rice starch into sugars and readies it for fermenting. It’s messier to work with than other strains of koji but has the power of tradition behind it. The whisky is made purely from rice—some grown in Okinawa, but most imported from Thailand.

Pollacchi notes that if Taketsuru hadn’t gone to Scotland and returned with a head full of knowledge about Scotch-making, Japan likely would have continued to develop its domestic rice whisky rather than pivot to distill from imported barley. “This is what I truly consider to be Japanese whisky,” Pollacchi says.

The initial releases range from whiskies aged eight years to 30 years. These include two 10-year whiskies, one aged in virgin oak and another in ex-bourbon barrels ($170), and 15- and 18-year whiskies aged in sherry casks ($230 to $300).

Pollacchi visited dozens of Japanese distilleries and sampled as many as 1,400 whiskies in searching for the company’s initial bottlings. Along the way, he was offered a sampling of a 30-year-old whisky from Okinawa, which he said was “one of the most interesting, sophisticated and just damn delicious whiskies.” He inquired how many casks were available, then told them, “we’ll take all of it.” The first limited release came out earlier this year, with a second bottling slated for later this year. Then it’s done until the distillery can age more. “It’s just stupidly good,” he says. The price? $1,069 a bottle.

Shibui is just getting underway in bringing Japanese whisky to the American market and is looking at changing things up in future releases. That includes extending the Scotch tradition by producing a blend using a selection of different whiskies from various Okinawa distillers—another break with tradition, as Japanese distillers tend to keep their product for themselves, and not sell or swap for blends. “That’s never happened before,” he says. “The Japanese don’t trade barrels or have options for blending.

“I think it would be really cool for myself as a Scotsman to help reimagine what Japanese whisky truly should be—considering it was a Japanese man who was so influenced by scotch,” Pollacchi says. “It’s been almost 100 years to the day since Taketsuru was in Scotland. I feel like there’s another part of that story that has to be told. And it’s exciting because we’re only scratching the surface.”