I’ve never been good at describing what it was like to land Pyongyang. “Strange” or “surprising” doesn’t cut it. It was real, but unreal. Otherworldly, yet populated. I imagine what space probe Philae might have felt this week, had it landed on that comet and found people already there.

And I categorically can’t begin to comprehend what it must be like to land at a military base back in the United States after having been held captive in North Korea for almost two years. But that’s the story of Kenneth Bae, the American missionary who finally Kim Jong-Un released this week. And it’s a story I have a limited but nonetheless vested interest. I was, for a time, in the thick of it.

Through a series of particular and peculiar circumstances, I joined Governor Bill Richardson—with whom I was writing a book about his many negotiations around the world—and Eric Schmidt of Google—whom I can thank for making it so darn easy to research that book—on a private humanitarian delegation to North Korea. This was less than two months after Bae had been taken captive. We’re talking Pre-Rodman.

Regarding Bae, our goals were both ambitious and modest. We hoped, if not to bring Bae home with us—a long shot, we quickly surmised—then at least to get the faintest hint of the remotest likelihood of the possible chance, that at some point in the not too distant future, if things were to unfold in a certain way, the North Koreans might release Bae sooner rather than later.

With a surprising amount of leeway, we bounced from foreign ministry to official “computer library” to Kim Jong-Il’s mausoleum to an acrobatic performance (that I must say, at risk of offending the French, put Cirque du Soleil to shame) taking every appropriate opportunity along the way to bring up Bae’s plight. That is, not in our caravan (we had been advised to keep the talk small, lest our minders hear something they shouldn’t), not while waiting in government lobbies (they were kept at a frigid temperature that would have made it hard to talk anyhow), and not most everywhere else—where, for some inexplicable reason, and almost without fail, we were treated to a Musak version of a The Cranberries’ Dreams playing in the background. (More on that particular diplomatic musical oddity in a later column, but suffice it to it’s all we ever heard, ev-er-y day, in ev-er-y POSS-i-ble way-aayyy—there has to be an explanation).

We made our case only where it mattered most: in long negotiations with key players at the highest levels of the North Korean government. They were delicate, they were long, they were polite, and they were long. (Did I mention they were long? As they should be.)

They were, needless to say, fascinating. Greetings were courteous and warm, requests were focused, translations were careful. Candor was given, confidentiality was appreciated. In the end, expectations were limited. Suffice it to say, we hoped, with Governor Richardson as our veteran QB, to advance the ball down the field a bit.

Maybe that was the wrong metaphor. If anything, we were setting the pick—for Dennis “the Worm” Rodman to show up a month later, sing birthday serenades to Kim Jong-un courtside, and make a very absurd, very public spectacle in the very absurd, very secretive Hermit Kingdom. That’s not an indictment; spectacles bring spectators. I called it “ding-dong diplomacy”; Governor Richardson wisely pointed out that “basketball diplomacy” is better than none. (It was later, when Rodman said Bae was guilty and should be imprisoned, that pretty much everyone agreed the Worm’s actions and words had “crossed the line.”) But admit it: at the first whistle, we all paid attention, to a part of the world that would usually prefer us all to butt out.

On our trip, we did our best to butt in. Ultimately, we didn’t meet with Bae himself nor did we get “The Interview” that might have trumped all over our preliminary negotiations (although we “didn’t get” the interview in a far different way than the Supreme Leader “didn’t get” The Interview). It’s hard to claim either of our primary missions—neither ours, nor Rodman’s, whatever that was—were accomplished back then. Bae was ultimately sentenced to 15 years hard labor.

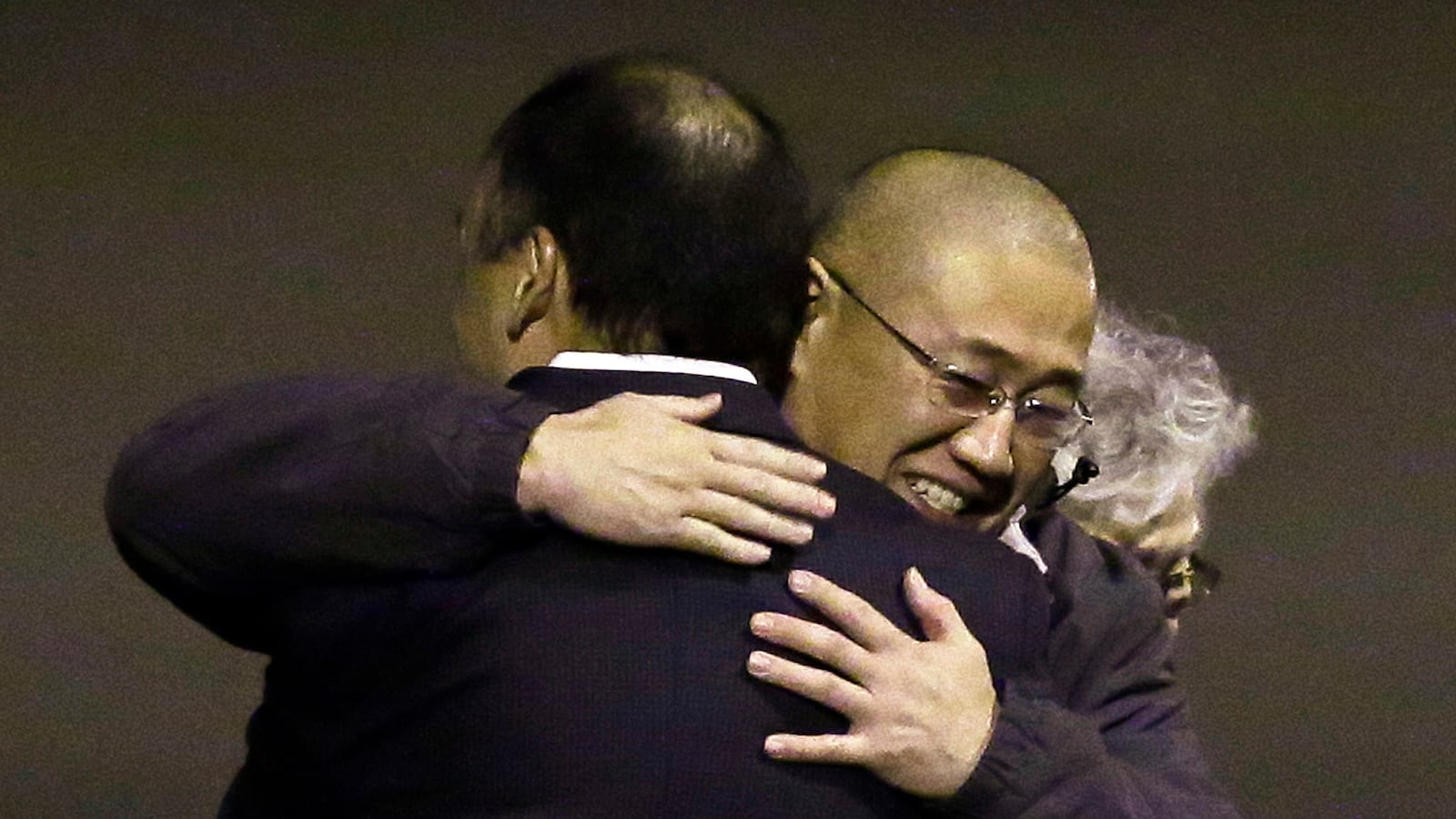

As we know now, it took the will and diligent efforts of the Obama administration and the will and flexible schedule of the Director National Intelligence James Clapper to get it done. Kenneth Bae is home now. After so long in such a strange place—and after many months of hard labor—I only hope for his sake that his return wasn’t like returning to a strange planet with people already there.