Twitter announced Tuesday that it’s done letting the QAnon conspiracy theory run rampant on its site, setting the stage to ban 7,000 QAnon accounts and limit the voice of roughly 150,000 more.

But Twitter’s crackdown comes too late to stop QAnon’s growth. While QAnon’s presence on Twitter will almost certainly shrink after the move, the movement it built on Twitter and other social media platforms has already moved into the real world—and established a foothold in the Republican Party.

Ahead of the deletions, panicked QAnon believers have attempted to evade bans on Twitter by changing up their spelling—now they claim to instead support CueAnon, or QANöN. “Praying Medic,” a leading QAnon promoter who blends late-night conspiracy theorizing with evangelical Christianity, temporarily deactivated his account in the hopes that Twitter will eventually give up on its purge.

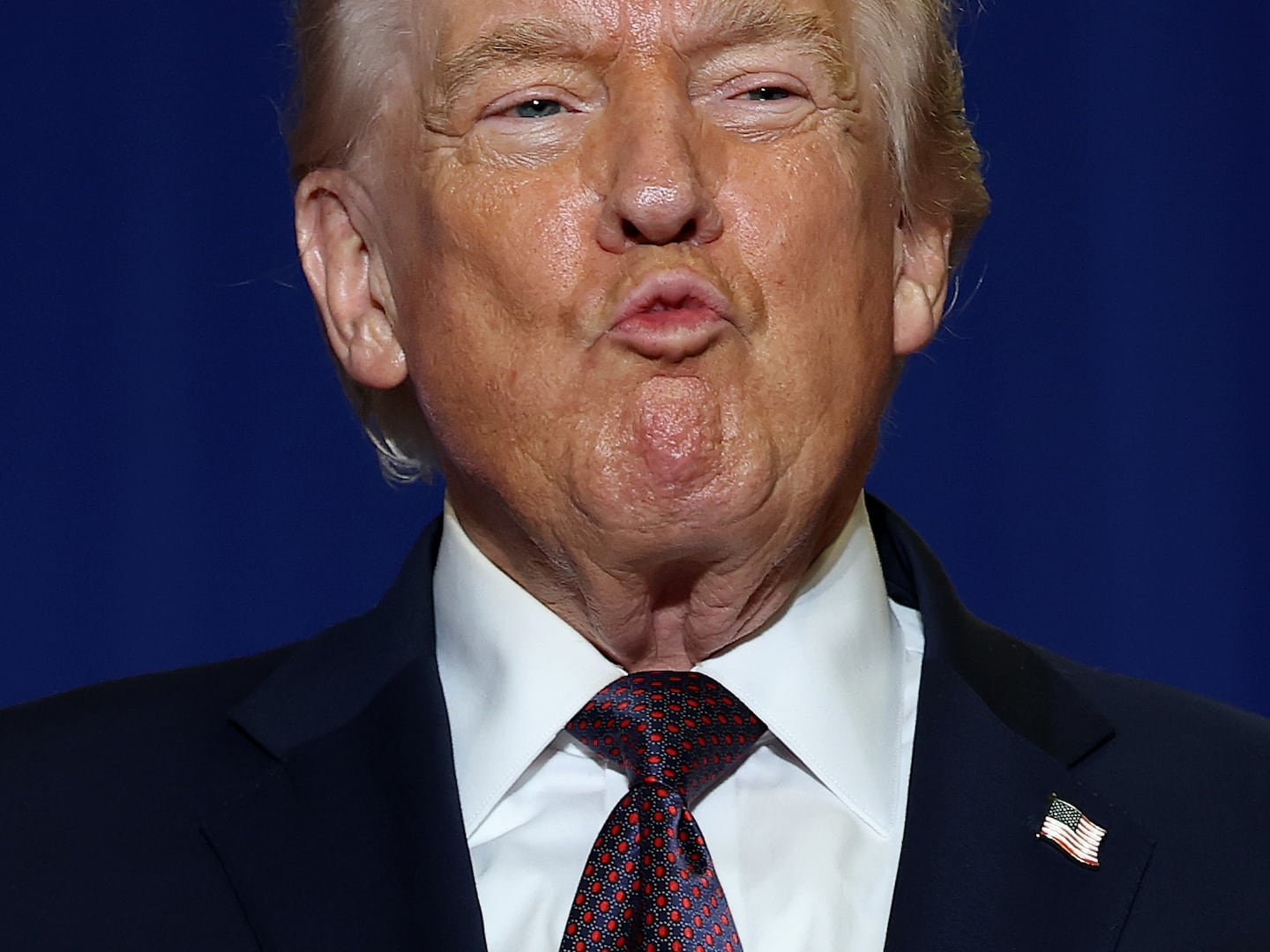

Twitter’s crackdown has been portrayed as a major move against QAnon, the pro-Trump conspiracy theory that posits that top Democrats and anyone else that QAnon fans don’t like is a cannibal-pedophile (or, in their telling, a “pedo-vore”) who will soon be arrested and executed by Trump.

Right-wing activists have traditionally seen their online influence drastically reduced, from anti-Muslim activist Laura Loomer to InfoWars conspiracy theorist Alex Jones. But the QAnon crackdown appears to be less of an outright ban on any QAnon promotion, and more of an attempt to reduce its circulation on the site.

Judging from Twitter’s description, for example, QAnon fans won’t necessarily be banned from the site. Instead, the new restrictions are meant to eliminate accounts that are already breaking other Twitter rules, while also trying to stop QAnon supporters from creating harassment mobs aimed at their targets.

In the real world, meanwhile, QAnon isn’t concerned about being banned. Its promoters earn invites to the White House, as the president retweets QAnon followers and Trump social media chief Dan Scavino posts a cartoon from avowed QAnon supporter Ben Garrison. Presidential son Eric Trump recently posted a QAnon graphic with a giant “Q” on it—probably not a sign that Trump is a closet Q-head, but more proof of QAnon’s ubiquity within MAGA world.

Former Trump national security adviser Michael Flynn recently filmed himself taking a QAnon oath with his family, thrilling QAnon followers desperate for proof that their dream of mass executions will come true. All of these Trumpworld nods to QAnon come even as the FBI considers QAnon a source of domestic terrorism.

QAnon’s rise to real-world power is especially baffling when you consider its origins: a handful of posts on the 4Chan message board in October 2017. The posts, from a still-anonymous figure calling themselves Q, claimed that Hillary Clinton would be arrested by the end of the month.

That prediction failed to come true, but those posts and the many Q “breadcrumbs” posted since then have spawned a thriving, and often lucrative, far-right subculture. QAnon encompasses a wide range of beliefs, from anti-vaccine activism to, for some, the theory that John F. Kennedy Jr. faked his death to team up with Trump. But just about all QAnon believers agree on the theory’s core tenets: that the world is controlled by a global pedophile cabal run by Democrats, and that Donald Trump is poised to arrest and execute them in a much-anticipated event called “The Storm.”

QAnon’s incipient takeover of the right isn’t just confined to social media. Boosted by a pandemic and a president who believes Barack Obama was born in Kenya, QAnon and the conspiratorial thinking that spawned it has never been more prominent. A QAnon believer who compared Q to Jesus won the Republican Senate nomination in Oregon. Another QAnon fan and congressional candidate is poised to win a runoff in Georgia in a heavily Republican district, meaning the conspiracy theory could soon be represented on the House floor next year.

Meanwhile, QAnon has started to seep into American life in other unexpected ways. QAnon billboards have appeared across the country. A boxing trainer appeared on a UFC broadcast decked out in QAnon slogans. The head of New York City’s police union appeared on television with a QAnon mug in the background—an ominous nod to a theory that’s predicated on vigilante justice.

The Twitter crackdown comes in a month where QAnon believers have flexed their muscles like never before on the platform, regularly seizing control of Twitter’s trending topics feature to terrorize large companies and celebrities, two keys to Twitter’s own growth.

The trending bar is supposed to tell Twitter users what matters on the site that day. Instead, QAnon fans used their numbers to cook up a bizarre theory that children were being traded and sold on furniture website Wayfair. And they harassed celebrity Chrissy Teigen with baseless allegations of pedophilia and cannibalism, until Teigen made her account private in the face of the onslaught and said she feared for her family’s safety.

A Twitter spokesperson claimed that the QAnon crackdown, which includes efforts meant to stop QAnon hashtags from trending, isn’t inspired by any particular incident.

“Based on a lengthy investigation and further assessment from our Trust & Safety team, we have seen a marked trend of QAnon accounts increasing their coordination and swarming to disrupt the public conversation across the service,” the spokesperson said in a statement.

Twitter’s new restrictions could limit QAnon’s spread on the site, but they were late in coming, according to Joan Donovan, the research director of the Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics, and Public Policy at Harvard University. QAnon is well-established on other social media networks, including Facebook and TikTok, the social media app popular with young people where the QAnon-adjacent Pizzagate conspiracy theory has flourished.

“These groups have strategically spread out across numerous platforms to protect themselves from losing their network,” Donovan told The Daily Beast. “Ultimately, unless YouTube and Facebook quickly follow up with similar removals, they will become a hive for this group trafficking in political and medical misinformation.”

Hashtags aside, there are even more obvious downsides to QAnon’s growth—ruined families, split apart by one member’s conviction that Hillary Clinton eats children, or the swathes of Republican voters who are increasingly divorced from reality.

There’s also real-world violence. One QAnon believer allegedly drove a Samurai sword into his brother’s head, convinced of the stories told by a splinter QAnon faction that the world was controlled by lizard people. Another allegedly shot the head of a Mafia family in an attempt to bring him to Trump’s mythical QAnon tribunals, ruining his own life in the process.

A military veteran in Arizona who became enamored with QAnon now faces a lengthy prison sentence after using an armored vehicle to shut down a bridge near the Hoover Dam to protest QAnon clues that had failed to come true.

Another man tried to burn down Comet Ping Pong, the Washington pizzeria QAnon believers are convinced is the hub of a global pedophile cabal. The arson attempt could have killed countless patrons, including children, if employees hadn’t put out the fire. Two women have been charged with QAnon-related plots to kidnap their own children.

So far, Twitter’s purge hasn’t extended to some of QAnon’s leaders on the site. As of this writing, many of the most visible QAnon accounts—including Jordan Sather, a QAnon promoter who encourages his fans to consume a substance the FDA warns amounts to drinking bleach—are still active on the site.

Dustin Nemos, a prominent QAnon promoter who was banned from Twitter earlier this year, feels confident that other QAnon believers will find out ways to remain on Twitter and keep pushing their message through hashtags.

“Maybe they’ll just hijack a Pepsi hashtag or something,” Nemos said.