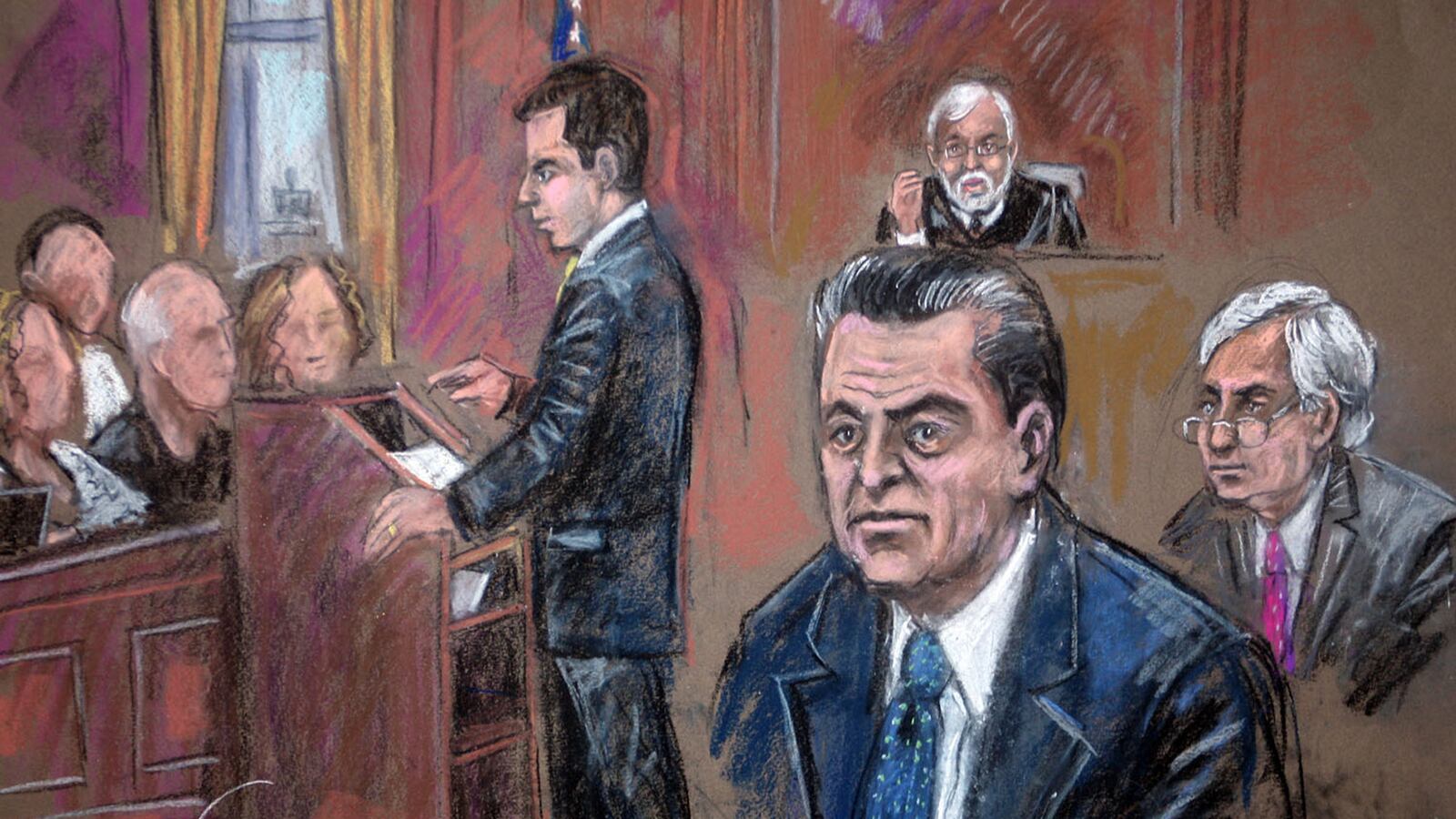

Of all the white-collar-criminal cases I have covered during the last quarter century, I may never have heard a more understated opening statement by a federal prosecutor than I did Monday, at the start of the insider-trading trial of Rajat Gupta, a man now known to the jury as “the ultimate corporate insider.”

Usually in cases like this, prosecutors harp on the notion that the defendant was blinded by greed. But in Manhattan federal court, Assistant U.S. Attorney Reed Brodsky didn’t use the word “greed” once. Instead he calmly told the jury Gupta had “violated his duties and abused his position as a corporate insider” by betraying his rank and reputation as one of the world’s most trusted advisers to “some of the wealthiest individuals and institutions in America.” The prosecutor continued: “This is a straightforward case of insider trading.”

Even U.S. District Judge Jed Rakoff noted that the prosecutor’s opening statement was “very low key” and “not in any way flamboyant or rhetorical.”

In response, Gupta’s defense team—led by the white-collar superstar Gary Naftalis—relied heavily on the notion that Gupta has done so much good during his long career that he never could have done anything wrong.

Complaining about Brodsky’s opening argument, Naftalis said, “He may not have used the word ‘greed,’ but that was the whole tenor of his case.” He pleaded with Rakoff to allow him tell the jury that Gupta was “a world- renowned leader in the fight to combat malaria, tuberculosis, and AIDS.”

Naftalis argued that it defied “common sense” that a man with such a sterling reputation would risk it all by stooping to insider trading.

It was an unusual approach for such skilled lawyers, and Rakoff didn’t buy it.

Naftalis instead traced Gupta’s legendary ascent from a middle-class background in India to Harvard Business School, the leadership of McKinsey, the world’s most trusted and important consulting firm, and access to the rarified inner sanctums of the world’s most successful companies. The defense attorney even pointed to Gupta’s wife and four daughters in the front row of the courtroom, noting that one had just graduated from Brown University and another from Harvard Business School.

“These are false charges. He is not an insider trader, he never defrauded anybody. He never cheated anybody,” said Naftalis. “He does not belong in this courtroom.”

Meanwhile, Brodsky methodically plowed through a list of Gupta’s alleged crimes.

While serving as a director on the boards of Goldman Sachs and Proctor & Gamble, Brodsky said, Gupta phoned in “secret information” gleaned from board meetings to his business partner and friend Raj Rajaratnam.

Gupta had invested $10 million with Rajaratnam in Voyager Capital Partners, which had doubled its money before losing everything in the market downturn of 2008.

Last year, Rajaratnam, the founder of hedge funds operating as the Galleon Group, was found guilty of 14 counts of insider trading and sentenced to 11 years in prison. He and Gupta are the most important Wall Street figures charged with such securities-fraud crimes since Ivan Boesky pled guilty in 1986 and helped prosecutors convict junk-bond king Michael Milken in 1990.

Brodsky highlighted a moment during the stock market collapse on Sept. 23, 2008, when Gupta, during an emergency conference call of the Goldman Sachs board, learned that fabled investor Warren Buffett was going to invest $5 billion to keep the eminent Wall Street investment bank afloat.

“Goldman was going to ride out the financial storm at a very turbulent time in the market,” Brodsky said. But “this big news,” the prosecutor continued, was “secret information” until the brokerage firm’s public announcement the next day.

“About 60 seconds after he hung up the phone [from the Goldman call],” Brodsky said, “he called his business partner and friend,” Rajaratnam, with the tip. With only six minutes left before the New York stock market closed, Brodsky said, traders at Galleon managed to buy $43 million of Goldman stock. The next morning, after news of the Buffett investment was made public, Rajaratnam sold his holdings for a profit of more than $1 million.

Saying Gupta “periodically” funneled secret information from board discussions to Rajaratnam, Brodsky acknowledged that the government has no direct wiretapped phone calls between the two men, as it did in Rajaratnam’s trial. Instead it will offer tapes of other calls in which Rajaratnam discussed having inside information on Goldman, and phone records showing Gupta’s calls.

Naftalis tried to capitalize on the lack of wiretaps, telling jurors the prosecutors had ”no real, hard, direct evidence,” and that they should ignore the government’s efforts to make them guess what really happened.

Brodsky also prevailed on Rakoff to limit Naftalis’s efforts to portray Gupta as a great humanitarian. Still, friends of Gupta, especially prominent Indian industrialists, have been posting testimonials to his charitable works and unimpeachable integrity on the website friendsofrajat.com, which, Bloomberg news reports, is managed by former McKinsey principal Atul Kanagat.On Tuesday, the first day of testimony, Raj Rajaratnam’s former secretary, Caryn Eisenberg, took the stand and stated that during her first week on the job in 2008, she was given a list of five “important people” whose calls she should always put through to Rajaratnam.

The list included Rajat Gupta, as well as four others, two of whom have pleaded guilty in connection with their dealings with Rajaratnam.

Gupta faces up to 25 years in prison on four counts of securities fraud and one count of conspiracy.