On a Saturday morning in late May of 1914, a funeral was held at Manhattan’s Hotel Netherland. Lying in repose there was Gertrude Rhinelander Waldo, a singularly unusual lady. Once heir to a vast fortune, she was now mired in debt. What family she had left alive either hadn’t spoken to her in years or were unable to attend her funeral, leaving it a lonely affair.

Her brother Charles, “90 years old, deaf, lame and suffering from many of the infirmities of old age,” according to the New York Sun, was one of the few to attend, despite not having spoken to her in decades following a feud. “She is dead,” he declared. “I feel no bitterness toward her memory.” Gertrude’s life had been dominated by her eccentric personality, her general misanthropy, and in the end, her woeful fiscal mismanagement.

“Mrs. Waldo was a woman of forceful manner and some unusual views,” the New York Sun proclaimed after her death in 1914. “She had no hesitation in declaring her opinions on a woman’s dress, art, music and society.” She was an abrasive woman, often making headlines for all the wrong reasons.

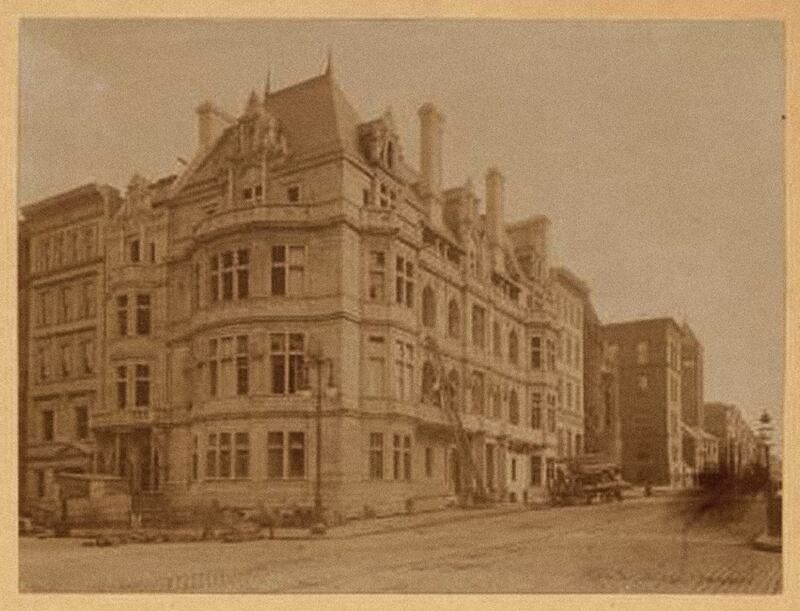

Her crowning achievement, and her most lasting legacy, was a pair of mansions she commissioned in 1895 for herself and her son. Sitting on a generous plot on the southeast corner of Madison Avenue at 72nd Street, Gertrude’s home was to be a palace worthy of her wealth and family name. (Her son’s matching townhouse stands next to it.) Five stories tall and more than 100 feet long on the Avenue, it was a mini chateau, reportedly inspired by one she’d seen on a trip to Europe. Today, it is better known as the flagship store for luxury retailer Ralph Lauren.

The mansion, when completed in 1898, boasted enormous halls, galleries, banquet rooms, and a full-floor ballroom, as well as a bowling alley and swimming pool. She filled its expensively finished interiors with crates of furniture, art, and antiques, but left it all to gather dust. She died across the street, hardly having set foot in her mansion, known by the press as her “house of mystery.”

Born in 1842 to Bernard Rhinelander and his wife Nancy Post, Gertrude was one of nearly two dozen Rhinelander heirs beholden to her grandfather William’s last will and testament. The will forbade the family lands and fortune from being divided in any way until the last of his children, including Gertrude’s father Bernard, was dead.

The Rhinelander family’s origins in the city are shrouded in some mystery, but their original ancestor Philip Rhinelander likely emigrated from France in the late 17th century. His son William Rhinelander established the family fortune through real estate investment in the city. William’s son, also named William, was Gertrude’s grandfather, and it was he who drew up the will which prevented the splitting of the family fortune.

Gertrude’s father, Bernard, was one of seven children born to William and his wife Mary Robert. Together, the siblings ruled one of the city’s largest collections of land holdings. Huge swaths of Greenwich Village and the Upper East Side fell under their control, with the Rhinelander name splashed across deeds and developments across the island.

Bernard Rhinelander died in 1844, when Gertrude was just two years old. She and her five siblings were raised by their mother in a brownstone on East 23rd Street near Madison Square Park. Their uncle William C. Rhinelander served as patriarch for the larger Rhinelander clan. The unofficial family seat was his stately red-brick townhouse on Washington Square North. (That home still stands, if only a facade, owned by NYU.)

In 1876, Gertrude married widower and stockbroker Francis Waldo, whose finances had been decimated by the Panic of 1873. Their first and only child arrived the following year: a son named Rhinelander Waldo. In June of 1878, her uncle William died, the last of his generation of Rhinelanders. His death freed the family properties and fortune to be divided among Gertrude and the rest of the family heirs.

Three months later, as inheritances were being sorted out, Gertrude’s husband Francis died, just 41 years old. Gertrude found herself quite suddenly a widow, a single mother, and charged with the care of a fortune estimated to be $2,000,000.

Gertrude’s eccentricities began to appear in the papers as early as 1889, when she filed a lawsuit against her lawyer and rumored lover Charles H. Schieffelin. In her argument, she alleged that Schieffelin fraudulently invested more than $12,000 of her money against her wishes, though he claimed she directed the risky investments against his better judgment and the money was lost to the markets.

The New York Times pointed out that the couple was “as nearly engaged to be married as is possible” though Mr. Schieffelin was still married to his wife at the time. “He and Mrs. Waldo were almost daily companions, dining together at Delmonico’s, spending days together at Manhattan Beach, and being seen often of evenings together at High Bridge, the parks, and other pleasant resorts.” Mrs. Waldo denied the insinuation.

Gertrude’s Madison Avenue mansion was designed by the architectural partnership of Francis H. Kimball and G. Kramer Thompson. As construction commenced in 1896, she was living at the Savoy Hotel (where today’s GM Building and subterranean Apple Store are located). There, she made headlines again when a scuffle with a housekeeper reportedly left her with a sprained shoulder and fractured wrist. Gertrude, who was “said to be worth about $1,500,000,” sued the hotel for damages.

Several months later she was back in court (and the news), this time suing a dry goods firm over some silk brocade she’d purchased 18 years prior. She went to court in the Bronx when her chauffeur was caught speeding. She went to court again when her carriage ran over a bicyclist and sped away.

She went to court when she had her cook arrested over a pay dispute: the maid thought she was owed $5 and Gertrude would only pay her $4.17. When Gertrude was unable to attend the cook’s appearance at night court, she tried to have the woman held in jail overnight. “Why, she is only a domestic and I insist upon her being held until morning so that I can appear against her.” The cook was released, much to Mrs. Waldo’s consternation, and later sued for wrongful arrest.

With each headline, Gertrude’s reputation as a wealthy New York eccentric grew. When her palatial home on Madison Avenue was completed in 1898, she chose not to move in. She opted instead to live across the street with her sister Laura. The mansion, along with the matching townhouse next to it which had been built for her son Rhinelander, sat empty and fell into rapid decline. The stone exterior became streaked with filth, its windows broken, its immense glass rooftop dome collapsed by heavy snowfall.

In short order, thieves began to frequent Mrs. Waldo’s empty house, carting off anything that wasn’t bolted to the floor. In the year 1909 alone, half a dozen robberies were reported, with thousands of dollars worth of items stolen, including a bronze statue of Gertrude. On one occasion, thieves were brazen enough to pull a wagon up to the house’s front door and begin loading it with fixtures and appliances from the kitchen. Watching this unfold, Gertrude sent a servant across the street to fend them off.

Gertrude seemed to feel entitled to special treatment due to her wealth and name, an entitlement which only grew when her son, Rhinelander Waldo, became the city’s Police Deputy Commissioner in 1906. “I’m Mrs. Waldo, the mother of your […] commissioner. We were not going too fast, and I’ll report you to Commissioner Bingham,” she once told an officer who had the audacity to try to cite her carriage for speeding. In the three decades since she came into her inheritance, she had done little more than spend money and fight court battles.

Over the years, Mrs. Waldo would occasionally entertain the possibility of selling her neglected Madison Avenue property, only to call off the deal at the last moment, perhaps because she didn’t like the appearance of the buyer, or simply because she decided not to sell after all. Her empty mansion stood as a derelict symbol, perhaps not only of her capacity to manage her wealth and responsibilities, but for the halcyon age of New York’s gilded palaces as a whole.

The death of Gertrude Rhinelander Waldo in May of 1914 made the papers as befitting a woman of her birth and status at the time. But her obituaries hinted at her tumultuous life, abrasive personality, and dwindling fortune. “Mrs. Waldo, as a member of the Rhinelander family, inherited a fortune estimated at $2,000,000,” lamented the Sun in 1914, “but friends yesterday expressed the fear that little if any of it is left.”

Indeed, Gertrude was found to be in debt to the tune of $136,670 at her time of death. Her Madison Avenue mansion, under threat of foreclosure, had been transferred to her sister Laura several years prior in an attempt to protect it and Gertrude. The home was sold in rapid succession over the following years to a series of real estate developers, none of whom seemed willing or able to put it to any real use. It continued to sit empty, a ruined testament to a lost fortune.

In the 1920s, as mansions up and down the avenues of Manhattan were demolished to make way for larger office and apartment towers, developers fought for the right to demolish Gertrude’s decrepit chateau on 72nd Street. But local zoning restrictions prevented the lot’s redevelopment, and it was instead carved into a series of retail shops and two upstairs apartments. More than twenty years old, the mansion at last had its first residents.

“Two attractive, unusual French housekeeping apartments recently completed,” the New York Herald advertised in 1922. One boasted twelve rooms and five bathrooms, the other fourteen rooms and six bathrooms. “The appointments are exceptional in every detail. Immediate possession. Rent reasonable.” Among the mansion’s early tenants were William May Wright and his wife Cobina, an actress and socialite. The couple threw lavish parties in their apartment, including a circus-themed masque in 1927.

The mansion’s ground floor was stripped of its elaborate stone detail, replaced by storefront doorways and large shop windows. Otherwise, Gertrude’s old mansion became an unlikely survivor in a city unaccustomed to preserving old things. Talk of landmark designation for the building began in 1964, less than a year after the old Penn Station had fallen to the wrecking ball. When it was officially landmarked in 1976, the city’s preservation commission called it “an exceptionally large and imposing structure, its opulence a reminder of the lavish scale on which many rich and fashionable New Yorkers lived in the late 19th century.”

By the 1980s, the mansion had suffered decades of abuse, most recently owned and used by neighboring St. James Church for “religious and directly related charitable purposes.” It sold in 1984 for $6.36 million to real estate developer Ian MacKay Kean, who specialized in revitalizing “historically grand spaces into commercial successes.” The plan was to restore the mansion’s faded glamor and make it appealing to some assemblage of high-end tenants.

What ultimately transpired, which would arguably transform New York’s retail landscape entirely, was that Gertrude’s long-suffering mansion would be leased out to an iconic fashion designer and retailer, fast on the rise at the time and looking for an appropriate place to cement his brand in New York City. What became of the marriage between Ralph Lauren and the Gertrude Rhinelander Waldo mansion would define the building’s next four decades.

Ralph Lauren, founded in New York in 1967, took control of the building’s restoration and opened its grand 20,000 square-foot flagship store there in 1986. At a cost of some $14-18 million, it was no easy feat. Virtually nothing of the original interior had survived the decades since Gertrude died. The grand staircase was completely gone, as was nearly all of the original wood detailing and plaster ceilings.

Restoration meant a lot of guesswork based on what remained and what original plans could be found, all coupled with a pragmatism as to the needs of the modern retail store it needed to become. The exterior facade was cleaned, its ground floor rebuilt as it would have looked prior to its 1920s commercial retrofit. At its peak, work on the mansion required some 400 construction workers, according to a 1989 New York Times article, “including 100 craftsmen and a dozen historical consultants.”

The result, as described in the New York Times in April of 1986, was “part American palazzo, part exclusive men’s club, part elegant women’s salon.” The company used the mansion’s Gilded Age credentials to sell its message of 20th-century aspirational consumerism. Lauren, a native New Yorker, saw the store as a reciprocal endeavor, not only cementing his place atop the city’s retail ladder, but also giving New York a landmark it could be proud of. “I didn’t need it for my business,” he said. “But I did it out of love for New York.”

When the mansion sold again in 1989 (Ralph Lauren remained the sole tenant), it brought $43 million, far more than the $6 million it had cost just five years before. It sold again in 2005 for $80 million. All the while it did nothing but gain a patina of refinement, an anchor for one of the city’s most exclusive shopping districts.

Today, for the majority of passersby, the mansion stands as a testament to Ralph Lauren’s seemingly eternal presence on Madison Avenue. Those who know anything of the building’s history might know anecdotally that it was built by a wealthy Rhinelander who never lived in it. But her story, like that of most people’s, was far more interesting than such a simplification.

The Gertrude Rhinelander Waldo house stands as a reminder of a lost age of wealthy eccentricity in New York, when fortunes were made, inherited, and lost over generations of diamond-encrusted heirs and heiresses. For every mansion like Gertrude’s which has survived today, a dozen more like it were lost to the wrecking ball, and with them went a version of New York which will never return.

Ralph Lauren speaks of the mansion as the fulfillment of a dream, but it also serves as a window to the past. Stand at 72nd Street and Madison Avenue and gaze upon this American chateau, and for just a moment be transported back to a singularly unusual time, and the life of a singularly unusual lady.