Henry “Poppa” Miller’s influence on Kansas City barbecue might have been completely lost were it not for Dan Turner.

Turner, a culinary arts instructor at the Johnson County College in Kansas, learned of this story, informed Doug Worgul, and connected him to Bob Miller, Poppa’s grandson. Worgul was so impressed by Miller’s story that he included a profile of him in his excellent book on Kansas City barbecue, The Grand Barbecue.

Most of what we know about Poppa Miller is from an oral history provided by Bob Miller. I just have to warn you that things might get a little confusing because we’ve got several Millers involved (a good thing, I think), and Bob Miller and his great-great-grandfather share a first name. From now on, the former is “Bob the Younger,” and the latter is “Bob the Elder.”

Poppa Miller was born in Oklahoma in 1861 to an African American mother and a Cherokee father. As reported in a local newspaper, Bob the Elder had “learned the art from an Old Indian barbecuer on the Indian Reservation” and, in turn, passed it along to his grandson, Poppa Miller. Bob the Elder taught him well. Poppa Miller eventually earned the title “The Barbecue King” after successfully barbecuing 15,000 pounds of beef, pork, and mutton for a group of Fort Arkansas businessmen in 1902.

Poppa Miller had quite the culinary résumé, cooking at various restaurants and hotels in Arkansas, Colorado, Kansas, Missouri and Oklahoma. According to Bob the Younger:

<p>Henry Miller was fluent in several Indian languages and was fluent in French and German…He also sold barbecue behind the house where he lived in Kansas City, Mo. He was also a master stone mason and had built many barbecue pits throughout the Kansas City area. He cooked for several years in Kansas City restaurants and hotels. A few of these were the Old Savoy in 1903, the Coates House on Broadway and the old Wishbone Restaurant. My father told me he was the cook that made the original Wishbone salad dressing. He would make the dressing often in his restaurant…Henry Miller moved to Leavenworth and got married to my mother [Clifton] and raised three sons.</p>

After getting married, Poppa Miller moved to Leavenworth, Kansas, and ran a restaurant renowned for its barbecue as well as its fruitcake. Poppa Miller attributed his fruitcake’s popularity to a secret ingredient—whisky. The problem was that Poppa Miller sold those fruitcakes during Prohibition, which made them illegal. He got caught, and it cost him a $100 fine and 30 days in jail.

Poppa Miller was unusual for his era in that local media took the time to interview him and treated him as a barbecue authority without trying to caricature or diminish him. From these interviews, readers gained rare insight into the mind of a turn-of-the-20th-century barbecue cook. One thing that is quite clear is that he held strong opinions about barbecue. In fact, if you know anything about Kansas City barbecue sauce, it may surprise you that he loathed one of its signature elements.

In a 1922 newspaper interview, Poppa Miller emphatically said, “Many barbecuers use tomatoes, Spanish sauce, allspice, and cloves in making a seasoning for their meats…This should not be done. Everyone knows that the flavor of barbecued meat comes from allowing the smoke of good old hickory wood to penetrate the meat, and not from any tomatoes or spice. I use a special sauce made by a secret recipe, which I have found to be the very best for use with barbecued meat. But it contains none of the ingredients which spoil the good old hickory smoke flavor.”

Some say that genetic traits can skip a generation, and this is certainly the case for this Miller clan’s disdain of tomato-based sauces. Bob the Younger, certainly channeling Poppa Miller, told Worgul:

<p>Now we all know how catsup, puree paste got into barbecue sauces. Today sauces aren’t even cooked. Most sauces are mixed loaded with preservatives and put into about three styles of glass and shipped. I call these sauces Johnny-Come-Lately sauces. They come from everywhere…Ever since tomato catsup was introduced into today’s modern barbecue sauce, people have been misled about barbecue sauce. Catsup is thick and lays on top of the meat or food it’s used on. Real old-fashioned barbecue sauce has no tomatoes in its contents. It is much thinner and is put on the meats for real barbecue taste. You don’t get the two different items mixed up. Real barbecue is where “finger-lickin’ good” originated.</p>

The Millers speak about BBQ sauce with a power that recalls Malcolm X’s stern warning: “You’ve been had! You’ve been took! You’ve been hoodwinked! Bamboozled! Led astray! Run amok!” News to all of us tomato-based barbecue sauce lovers, including me. What then provides the base instead? These Millers had a strong affinity for the vinegar-based barbecue sauces often tasted in the Carolinas and Virginia.

The pinnacle of Poppa Miller’s barbecue career was also a glorious homecoming. In late 1922, the Oklahoma governor-elect John C. Walton inauguration committee contacted Poppa Miller, and they called on him to travel from Kansas to help prepare a mammoth barbecue. Poppa Miller’s local newspaper announced: “Henry Miller…the barbecue king…has been called to Oklahoma City, Okla., to take over the preparations to be given at the inauguration of the governor of Oklahoma.” When it came to large-scale barbecues, 19th- and 20th-century newspapers were notorious for their hyperbolic estimates of the number of attendees. If the estimated 150,000 attendees for this barbecue is accurate, it was arguably the largest barbecue in recorded world history.

Walton had pledged as a candidate that “when he got into office he would hold an old-fashioned barbecue and dance for everyone in the State.” It’s unclear whether Miller actually made the trip and superintended the monstrous affair. Other media reports indicate that I. R. McCann, a white man from Pauls Valley, Oklahoma, was actually in charge. If Miller ever elaborated on his role at that famous barbecue, it has not yet been found.

That inaugural barbecue cost a whopping $100,000 in 1923, roughly $1,549,285.71 in 2020 dollars. Take a gander at the shopping list, and you’ll see why: 100,000 buns, 100,000 loaves of bread, 5,000 chickens, 1,000 pounds of pepper, 1,000 rabbits, 1,000 squirrels, groundhogs, and frog legs, 1,000 turkeys, 500 beef cattle, 500 ducks and geese, 250 bushels of onions, 200 hogs, 200 possums (and “sweet taters” to go with them), 10 bison, 10 bears, 10 deer, 10 antelope, 5 tons of coffee, 5 tons of salt and 5 tons of sugar.

After Governor Walton’s inauguration, Poppa Miller spent the rest of his days in the city of Leavenworth running a barbecue restaurant near a bustling military base, operating a gas station, and traveling to several states to oversee barbecues for many prominent politicians.

Worgul wrote: “Poppa Miller died in 1951 at age 90. Bob [the Younger] says that his father remained amazingly strong and active right up until the end. ‘Even when he was 90 we would still go out together with our two-man saw to cut hickory, oak and apple wood or barbecue,’ Bob says. ‘He was cooking barbecue on the day he died.’”

I think that’s a fitting end for the extraordinary life of a celebrated barbecue artist.

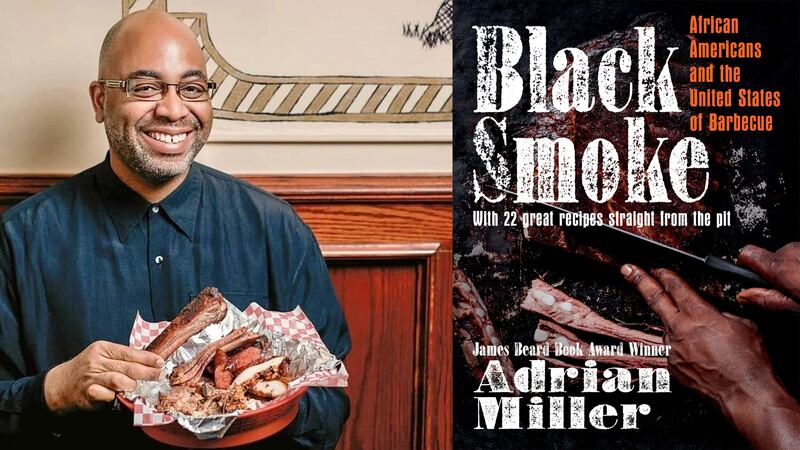

From BLACK SMOKE: AFRICAN AMERICANS AND THE UNITED STATES OF BARBECUE by Adrian Miller. A Ferris & Ferris Book. Copyright © 2021 by Adrian Miller. Used by permission of the University of North Carolina Press.