What is it about fires? Why can we gaze endlessly into dying embers and speak truths or share dreams with the people we’re sitting next to, with little sense of time? Fires are totally mesmerizing. Why else would Richard Nixon have lit a fire in the White House in D.C.’s sweltering August heat the night before resigning? What’s roasting marshmallows on a camping trip all about if not finding a way for kids to safely engage with this fascination—initiates as both fledgling fire tenders and cooks.

I love everything about a real wood fire: gathering tinder; the one match challenge; smelling the resiny odors; hearing the cracks and snaps of burning logs; feeling the warmth from the slightest flame, an immediate antidote to the chill creeping in as the afternoon light fails. The smallest curl of smoke exiting a chimney announces that civilization is staked out here. People leap to call someone like me a pyro, as in a pyromaniac, which implies aberrant behavior, someone akin to an arsonist. On the contrary, I believe that part of our humanity is to love the magical transformation of the forest into heat and light. It’s an alternate sun, an earthbound source of warmth and light. Call me a pyrophile.

Most of all, I love the taste of the fire in my food and the perfect dry roast obtained from fireplace cooking that no designer oven can ever offer. My first self-cooked meals were prepared on camping trips over an open fire. Those delicious meals—made even more delicious after hiking all day—had the added bonus of being prepared without the modern conveniences of a gas stove or a refrigerator and primed me for more culinary explorations.

ADVERTISEMENT

Beyond its immediate pleasures, being able to elicit a satisfying pot of oatmeal over a reluctant fire from damp wood, softened me up to all kinds of challenging conditions to come. It defined my outlook that I can cook anywhere, on anything, an attitude that has served me well. Fuel, pot, food, ignition: that’s all I need to cook dinner. Anything else is a bonus.

Prior to taking possession of the Crosby Street space, I suspected that there might be a fireplace hidden behind the luncheonette’s stainless steel wall lined with coffee urns and a flat griddle. There were fireplaces upstairs and my measurements confirmed a two-foot discrepancy between the exterior width of the building and its interior width. Upon getting the keys, I immediately suited up in the denim coveralls that would be my uniform for the next five months and pried away some of the grease-laden stainless steel on the back wall. Jackpot! There was a brick projection directly beneath the fireplace upstairs and open space in between two brick outcroppings indicating a hearth of some sort. I was ecstatic, triumphant even, although I knew hadn’t accomplished much beyond a bit of demolition. But the discovery of the fireplace confirmed the worthiness of my site selection and fueled my excitement. It was a good omen to be sure.

I was convinced that it was worth having a real working fireplace in a New York City restaurant regardless of the renovation cost. Many tried to dissuade me, saying that a fireplace was an indulgence that would become more of a nuisance than a useful amenity. I knew otherwise and could not be deterred. Surely there were spots that had propane gas fireplaces with faux logs but very few that had the real thing. I knew that even a 10 percent increase in the construction budget would repay me many times over. It would be singular and go a long way towards communicating the openness, warmth, and lack of pretension we were trying to create. If the first smart thing I did was discovering this backwater location, then the second was committing to the restoration of the flue and chimney regardless of the cost.

I knew intuitively that wood-burning fireplaces are not mere embellishments but anchors of civilization and comfort in a room. Ours would offer New Yorkers a marvelous reprieve from the harshness of urban life or the chilling winds barreling down Broadway. Our restaurant did become that cherished refuge. The fireplace, along with the two that we added later when we expanded to the second floor, was a major element in establishing Savoy’s reputation as New York’s most romantic restaurant. During heavy snowfalls couples would trudge through the snow to sit by the fire. January, a traditionally slow month in New York City restaurants after all the December partying, would consistently be either our second or third best month of the year. People longed to take in the fireplace and the hearty winter fare we paired with it.

Our masons suggested that we lift the hearth off the floor to give us a place to store firewood and to offer customers an eye-level view of the fire from their seats. Predictably, everyone wanted to sit near the fireplace. During the winter, a day didn’t go by without someone making a reservation request to sit near it. The pressure mounted around Valentine’s Day when callers would try as early as November to reserve a table for February 14 and try to convince us that the entire future success of their relationship depended upon getting a fireside deuce. Our percentage of marriage proposals in house was quite high and I know of at least one baby who was conceived after a romantic dinner at Savoy, although I am quite sure there were many others. Cooking in the fireplace came later. On a whim, during our first New Year’s Eve, I stationed a cook by the fireplace to grill shiitake mushrooms over a small hibachi pushed into the hearth. Aside from the complication of coordinating service with the kitchen, it was clear that this was great theater for the diners, added great flavor to the food, and took another step towards connecting our visual aesthetics with the simplicity and directness of our cooking. If we were committed to pulling back the curtain on where our food comes from, how it is cooked and who is cooking it, then this took us three giant steps closer. I bookmarked this idea, for later use.

Mom-and-pop restaurants are rarely as finely planned as a newly built and well-capitalized restaurant: the coatroom might be a temporary rack set up in a fire exit corridor, the bar might double as the host stand with no actual greeting area at the entry door, deliveries and trash disposal might be through the front entryway, and pastry production might be staggered with savory work because there is only one oven and limited work space. A lot gets shoehorned into very small spaces and priority is always given to seats, i.e., direct revenue generation.

Compromises: we all have to make them, but small restaurants in high-rent districts trying to maximize use make lots of them. I was able to get building department approval for only one bathroom because the premise was a pre-existing restaurant but for even a wine and beer license, the State Liquor Authority (SLA) requires two bathrooms. When the approved drawings came back from the building department, I whited out the representation of the toilet, drew a pencil line down the middle to create a separating wall with two toilets, made a Xerox copy for the SLA and sent it off to Albany. Approved. Those days are gone.

The most challenging condition for us was not having an area to wait for a table. Diners with reservations would gather just inside the front door, which also happened to be right on top of the phone and host stand as well as near the entry to the bathroom and a few feet away from the kitchen door. Hooks for coats lined the wall from the front door to the phone stand. When we were cranking, the host was on the phone trying to take a reservation, the waiters were trying to clear and reset tables, customers were trying to get to the single bathroom toilet, and the holding area at the door would become increasingly restive if a waiting guest’s table wasn’t ready in a matter of minutes. When our largest table and only six-top would finally turn, the exiting diners had to push past the six others waiting to take their place all while retrieving their coats. I’m not one for foul language, but I think the word clusterfuck accurately describes this moment.

We were aching for more space, not just to do more business but to do better business, to offer a nicer dining and work experience for everyone involved. The opportunity came just a few years later in 1995 when we were able to expand to the second floor. It couldn’t have come at a better time. Susan and I had started a family; our son, Theo, was three when the second floor opened and our daughter, Olivia, was born the following summer. I wanted flexibility to be able to be with my kids during their waking hours, to read bedtime stories and to be involved in their social and school lives. Nothing out of the ordinary, it’s what most parents want and struggle to accomplish. This desire for balance meshed nicely with the growing needs of our key managers, John Tucker, the general manager, and David Wurth, the chef de cuisine. Both had been with us for several years and needed bigger challenges and fatter paychecks. I proposed offering them each 10 percent of any company disbursements in return for a three-year commitment.

Delegating responsibilities to managers who were completely committed to our success gave me the sense of security and stability I needed going into the expansion and to be with the family more frequently. I trusted that increased revenues from the expansion would pay for the profit-sharing arrangement. It was attractive to John and David too; they would receive a bonus if the restaurant thrived and we now all sat at the table when discussing operational and strategic plans for the restaurant. I drafted a simple agreement and we all signed it.

More than anything else, the restaurant needed a waiting area to transform that nightly barrage of bodies at the door into a civilized experience. In other words, we needed a bar, a lounge, a coat closet, and a second bathroom. Additional dining space, a place for a cocktail before dinner or an after-dinner nightcap were all welcome and potential revenue boosters, but that wasn’t the initial goal. Believing that we couldn’t integrate the two floors and serve from one kitchen—David wanted limited involvement in the expansion project—I began to think about independent concepts, a restaurant within a restaurant, similar to Chez Panisse only in the reverse, where they serve a prix fixe menu downstairs and run an à la carte menu upstairs. The fireplace seemed like the obvious focus for the dining experience. I remembered my New Year’s Eve fireplace shiitakes but also an older and more fundamental conversation that I had in 1985 with Richard Olney, the cookbook writer, during a visit to his home in southern France. Sitting in front of his stone cooking hearth, lined with mortars and pestles in graduated sizes, various iron fish grates, a small adjustable grill, and a clockjack rotisserie, all the accoutrement necessary for superior hand-hewn food, Richard pontificated on the inherent structural failure of restaurants to deliver excellence. His critique was that from the inception of the restaurant, when public cooking transitioned from the tavern, with its preparation of a single dish served to all the guests, known as table d’hôte, to the restaurant setting where individual choice was offered, à la carte, soul had been lost in the food itself. There had been a tradeoff: the ability to compose individual plates in a sophisticated setting gained, the power and depth of flavor that comes from whole joint cookery in a communally seated tavern lost. A measure of control over the meal was also lost; the chef had ceded power over to the dining room.

Cooking à la carte means being able to accommodate groups of varying sizes at different times. This necessitates deconstructing a dish into its constituent parts so that they can be partially prepared and then assembled when the dish is actually ordered. Animal proteins get cut off the bone into individual four-or five-ounce portions and vegetables are blanched separately in water to advance their cooking and reduce the time necessary for what we call “pickup,” the final preparation of the plate. Although this approach is in keeping with the comptroller’s directive that portion control is key to the financial success of a restaurant, it also is a style of cooking that can never approach the quality of flavor achieved when all the elements of a dish are cooked as an ensemble and their flavors meld together. Richard counseled that this mechanistic approach was antithetical to good cooking, more akin to manufacturing and, as with all manufactured items over handcrafted ones, there is a resultant decline in quality, in this case flavor. Instead, he lobbied for cooking whole dishes, birds roasted on the spit, fish on the bone, entire saddles and haunches of lamb roasted over embers, gratins cooked and served when done, no holding time. Before we sat down to lunch I made a careful pen-and-ink sketch in my journal of his clockjack, or tournebroche, a small spring and gear wind‑up rotisserie designed for fireplace cookery, the anachronistic tool in his fireplace that most intrigued me.

The next several pages are recorded in wildly loopy cursive, no doubt a direct result of all the wines we drank over lunch, ending with multiple tumblers of 1900 Grand Champagne Cognac from Lucas-Carton, the famed Belle Époque Parisian restaurant. Listening to him, I began to fantasize about a restaurant concept in which large-format celebration dishes were the focus of the cooking, and the meats and fishes were cooked on the bone. I returned home still intrigued by both the mechanical gadget and the idea of trying to cook in less mechanistic ways. It went against everything I had learned and practiced in restaurants up to this point. As the sole concept for a future restaurant it clearly wasn’t going to work. That’s not how restaurants are generally organized and though I was familiar with swimming against the tide, I knew that the framework needed to be recognizable.

I developed a plan for the second floor dining experience that moved us in this direction. I thought that if everyone was eating the same meal even if at staggered times, we could elevate the quality of the food and alter the way we thought about menus and menu development. We could get out of the manufacturing mindset, compose dishes that were less about an assemblage of deconstructed parts and more about home cooking at its best.

I built a small professional kitchen in the galley area where the residential kitchen had been and had a skilled Italian mason build out the fireplace to accommodate our goal of trying to do restaurant cooking in it. In designing a small kitchen and dining room independent of the main kitchen with a separate prix fixe menu, I created a laboratory for culinary experimentation. I could offer young talented cooks the opportunity to explore their cooking style without being burdened by all the complications of running an extensive menu and the staffing needed for execution. It became the breakout kitchen for some terrific cooks: Caroline Fidanza, who went on to become the first chef of Brooklyn’s renowned Diner and owner of the beloved sandwich spot Saltie; Andrew Feinberg, later chef- owner with his wife, Francine Stephens, of Franny’s; Jody Dufur, Westchester chef; and Todd Ahrens, the kosher chef at one time of Baron Herzog Winery. All of them used the opportunity to create carefully curated meals and deeply delicious food. Each night we offered a set three-course menu largely composed of hearth dishes that changed on a daily basis. I was committed to giving a taste of the fireplace in every meal, year-round.

We began to learn about cooking with live fire. I bought a version of Olney’s tournebroche I’d captured in my sketchbook, using it for guinea hen, rabbit, chicken, and capon. We discovered that there are all kinds of areas close to the flames that allow for gentle cooking or give a hint of smoke to the food. We could cook lamb à la ficelle, French for “on a string,” by tying a leg of lamb onto the chimney damper lever and then twisting the joint in one direction and allowing the string to unwind and rewind in ever-shortening alternating revolutions, much like the way a twisted playground swing alternates the direction of its revolutions until coming to a stop. The string didn’t burn and the slow radiant heat was a superior cooking method, far more gentle than a grill, without any of the trapped moisture of an oven or the dehydrating effects of a convection fan: a true roast. We loaded up Mason jars with dried beans, garlic cloves, a fistful of herbs on the stem, salt, a healthy shot of olive oil, all topped off with water and set them six or eight inches away from the fire’s center. Over the course of their meal, customers watched the slow-motion theater of a see-through pressure cooker next to the burning logs produce the most unctuous and flavorful cooked beans imaginable. Called al fiasco because traditionally Italians use a wine bottle for cooking the beans, this is a safe and simple technique that anyone with a fireplace can try. It produces some mighty stellar beans. It wasn’t long before we expanded to cooking cassoulets in the fireplace and teaching waiters how to tend to the stew and then serve it tableside.

William Rubel, author of The Magic of Fire, taught us how to bury vegetables in the embers and slow roast them there: sweet potatoes, onions, carrots, squashes, from which we made salads or side vegetables. In the summer we cooked more in the back kitchen but remained committed to one item from the fireplace in every meal. We would light a fire in the afternoon, smoke some fish for an appetizer or roast vegetables, and then dress them with a vinaigrette of sherry vinegar and pimenton, the Spanish paprika made from peppers dried over a wood fire, accentuating the fire elements of the dish.

The tool and the dish that became the signature for the dining room experience was the iron salamander, essentially a branding iron that got its name in the seventeenth century because people thought it looked like a salamander with its “head” buried in the coals, its “legs” propped up on the hearth, and its “tail” the handle. We used it to finish off crème brûlée: burning granulated sugar sprinkled atop a gently cooked custard to create a thin sheet of brittle caramel reminiscent of my best marshmallow moments. We gave every diner a taste of the fireplace at the meal’s conclusion regardless of whether or not they opted for dessert: a mini crème brûlée. The dramatic puffs of burning sugar caught everyone’s eye but the fragrance was marshmallows by the fire, a hundred percent. As charming and delicious as the experience was, the fireplace prix-fixe menu was a tough sell. Maybe it works in more community-minded Berkeley or because Chez Panisse has a few decades of international fame under its belt, but New Yorkers don’t like being told they don’t have choice. Masters of the universe get twitchy when they lose control, especially of what they are eating; they don’t take kindly to being told what to do under most circumstances. Countless parties would book and then call back saying “I’m not sure if my business associate eats fish” or “My partner doesn’t eat squab so I’m going to have to cancel.” In the second year we offered a choice in the entrée course: a meat or a fish. That helped. We also began to write a menu for the week instead of trying to change it every night, giving us more time to polish the dishes and for everyone to practice describing the food. In the third year we offered a choice in every course. It never ceased being an uphill battle. It also wasn’t efficient. Running two menus with two sets of mise en place created more waste and increased the number of ingredients subject to deterioration. Chef up and chef down didn’t always happily play in the sandbox together and coordinate buying. Labor was also inefficient. Executing the upstairs menu wasn’t a one-person job when we were busy but not really a two-person job either. I would hire swing shifters or offer culinary interns assistant shifts.

During a very slow summer, I happened to be interviewing a potential new accountant. When I told him that the two dining rooms were booked separately and that we did not allow diners to eat from the downstairs à la carte menu in the upstairs dining room—even if we were fully booked downstairs—he looked aghast, set down the dismal profit and loss reports we were reviewing and said, “You can’t do that.” The sickening truth was that I knew he was right. I’d had a notion of what I wanted to do, but I was turning away interested diners and with them the money needed to pay rent and salaries. Looking back across the table at this accountant whom I didn’t really know, I couldn’t hide from the truth or continue justifying my complicated, labor-intensive pet project. After four years of tweaks and recalibrations I finally admitted that it was unsustainable.

I anxiously approached Nicole Wester, the downstairs chef at the time, and asked what it would mean to serve the à la carte menu upstairs. Ever the optimist, she just shrugged and said, “It’s OK. We can do that.” Not a patsy by any means, especially in the face of all the chauvinistic pushback she got from certain male cooks uncomfortable taking direction from a woman, Nicole would say yes whenever she could. It was a huge relief; buy-in from everyone on the staff is important but from the chef it’s critical. My best chefs were ones who knew how to offer hospitality from the kitchen side, who found ways of saying yes to accommodate customers and owners while still remaining committed to their artistry and holding a high standard for the food. A waiter’s or manager’s primary responsibility is to be hospitable and accommodating whereas the kitchen staff’s primary responsibility is to make delicious food. Good social skills, however, are harder to come by. Historically, a lot of ingrained negative behaviors by chefs were tolerated, creating divisions between the front and back of the house. I always worked hard to dismantle these old habits. Those with more rigid views of their role either cycled themselves out or I had to remove them from our culture by firing them.

Thankfully at this critical moment this wasn’t the case. Even though the prix fixe menu concept didn’t prevail, the fireplace remained the heart of the restaurant. People still came because it gave them the feeling that they were in a country inn or in someone’s home outside of the city, far removed from the multitude of churn and burn spots. I had taken Richard Olney’s un-restaurant vision of fine food and melded it with who I was as a chef, thinker, and restaurant operator in New York City. Echoes of his viewpoint always reminded me to protect good taste and good cooking in the restaurant. The hearth is always the center of the house.

Serves 4 as a side dish

Fireplace cooking doesn’t require fancy equipment. All that’s needed is a Mason jar. Lacking a fireplace or a campfire, the beans can be cooked in a covered pot but it is less dramatic. The slow, even cooking produces wonderfully flavorful beans, and the glass is a window into the cooking process. The method utilizes the heat of a mature but not roaring fire. Traditionally done in a wine bottle (fiasco in Italian) the Mason jar lets you easily spoon the beans out of the jar. Serve with grilled meat or wilted greens. I prefer Sorana beans but scarlet runners or cannellinis all make great versions. Avoid white navys. They are inferior in flavor and texture.

INGREDIENTS

- 1 cup Dried beans, soaked overnight

- 5 Garlic cloves, peeled

- 1 (5-inch/12 cm) Sprig rosemary

- 1 Bay leaf

- .5 tsp Salt

- 1 tsp Freshly cracked black pepper

- .33 cup (75 ml) Good olive oil

DIRECTIONS

Combine all the ingredients and 2.5 cups (600 ml) water in a (1-quart/960 ml) Mason jar. Place the lid loosely on top—steam needs to be able to escape during the cooking process. Set in the hearth of the fireplace 8 to 10 inches (20 to 25 cm) from the active fire. Feel with your hands that this distance is hot but not unbearably so. Rotate the jar every 15 minutes for the first hour to ensure even cooking as the beans begin to simmer. After 2 hours check to see if all the liquid has been absorbed. Taste them to see if the beans are fully cooked. Add more water if necessary to complete the cooking. When the beans are tender and brothy, they can be served immediately. Allowing them to simmer overnight in the fireplace as the fire dies down produces a caramelization of the bean against the jar walls that is delicious and a consistency more like a rough puree.

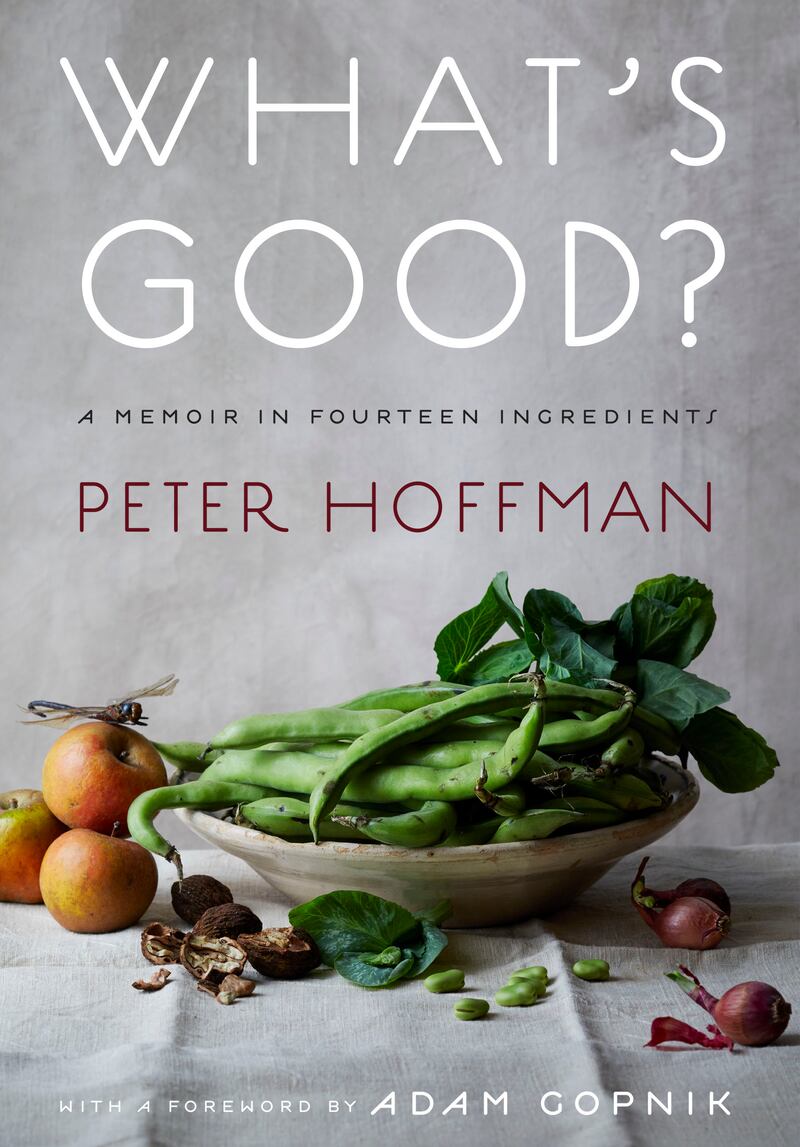

Excerpted from What’s Good?: A Memoir in Fourteen Ingredients by Peter Hoffman. Published by Abrams Press © 2021.