For three days and three nights, on a damp February weekend in Palm Beach, Florida, I read Nabokov to Nabokov. I had traveled from New York to Palm Beach with a manuscript in my suitcase to visit Dmitri Nabokov, the only son and literary executor of Vladimir Nabokov.

The manuscript, my first book, contained a number of Nabokov quotes for which I needed to obtain rights before I could approach an American publisher. I knew that, in 1999, Dmitri had threatened to sue an Italian author named Pia Pera over a book titled Lo’s Diary, a rewriting of Lolita from Lolita’s point of view. To avoid an infringement lawsuit, Pera’s American publisher had printed a scathing preface by Dmitri (“Pia Pera [henceforth PP], an Italian journalist and author of some stories that I have not read …”). Aside from this, Dmitri had built a forbidding reputation in the literary world for attacking the works of many a would-be Nabokovian. Fearing the worst, I had emailed Dmitri the manuscript, hoping he would read it before I made it to Florida, and that we might spend the evening discussing potential issues.

My book was a curious combination of fiction and essay, of invention and interpretation. It posited that Nabokov was the great writer of happiness. A notion that, over the years, almost invariably turned small talk into opinionated tirades. Happiness, evidently, did not keep good company with nymphets and nympholepts.

Palm Beach felt like a sort of grotesque inversion of Nabokov’s short story “Spring in Fialta”: gigantic pine trees; juniper shrubs; sorry-go-rounds of concrete high-rises. With a map and a bicycle, I’d made my way to Ocean Drive. I rehearsed with myself how I might parry various lines of attack: breathe, acquiesce, qualify. “Your father hated didactic writings, hence this book had to be extremely playful ... I had to imagine him.” With an accelerated heart rate, I rang the bell of Dmitri’s apartment. A beaming nurse opened the door, and I stepped into a living room adorned with posters outlining, in 19th-century font, the casts of productions Dmitri had sung in during his operatic career. La Bohème stood out—a memorable performance, as Dmitri later recounted, at the Teatro di Reggio Emilia, where he had sung his debut role on the same night as Pavarotti, nearly half a century ago. On the door to his bedroom, to the left, a glossy poster of Kubrick’s Lolita displayed the famous pair of heart-shaped red glasses. Among mirrors and modern cream-white furniture, one could glimpse various miniature models of racing cars, another of his life’s passions.

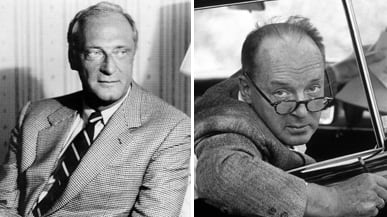

Dmitri himself, now 76 and looking uncannily like his father at about the same age, was seated in a wheelchair, at the head of the dining table. To his left was Ariane, a blond lady with an edgy sense of humor who turned out to be an old friend of Dmitri’s, and like him a former opera singer. Dmitri’s ice-blue eyes looked dazed and sleepy that night. Ever the gentleman, however, he announced that he, together with Ariane, had read and appreciated the first two chapters. The most conventional ones from a narrative standpoint, I immediately thought to myself, and felt my temperature drop. He had read only a fragment, and everything remained uncertain. I joined them at the table for a three-course meal, and tried to ease into a semblance of small talk. He could yet hate, and kill, the book I had worked on for the last several years. A moment later, Dmitri Nabokov looked up, smiled, and declared he had come up with a good idea. He was too exhausted to read the manuscript, he confessed, so would I kindly read it out loud to him over the span of the next few days? I glanced at Ariane, who nodded in agreement.

For the past 20 years, Dmitri has been a remarkably meticulous translator of his father’s earlier works, from Russian to English and Italian. Last year he edited and oversaw the publication of the unfinished manuscript of Nabokov’s last novel, The Original of Laura. But during those three marathon days in Florida, he remained in bed, and I sat on a chair by his computer and read to him. As I started off on chapter three—the chapter on his father’s first loves—bursts of “SLOWER!” and “LOUDER!” punctuated our hours. Dmitri had been a basso profundo singer, and to this day retains a commanding voice as well as a keen ear. I must have driven him mad, as I garbled my words and raced erratically through clusters of sentences that looked clear on the page but sounded barely intelligible as I spoke them. At the end of each evening, he would begin to nod off, and I bicycled my way back to the hotel.

As the days and nights unfolded, my heart often pounding, I read to Dmitri passages from Lolita, Ada, or Ardor, Speak, Memory, and countless short stories, but also imaginary interviews and fictional accounts of his father’s erotic life. The page at times elicited fierce reactions, even fits of anger (“Why, please tell me why you need to invent this? It almost sounds too close to home!”), but also moments of gentleness. His critical ear remained sharp throughout the reading. He not only critiqued and edited, but also corrected grammar (“Is it onto or unto?”), diction (“Vladimir and his mother would never ‘argue’ over a weak serve! Perhaps you meant ‘squabble’?”), and, most precious of all in my sense, pronunciation. Dmitri or I often picked up the dictionary to check British and American variations, and sometimes, to my relief, found we were both right, as in the case of “skein” (pronounced both “skeen” and “skeyn”). Dmitri also taught me to pronounce the names of butterflies ( Ly’caeides Samue’lis), myriad plants, and the Latinate shades of many other words I had read and written but never said aloud.

My mother, though Iranian, had taught me English exactly two decades before in Paris (where I was born)—irregular verbs, vocabulary, tonic accents, and modulations. As Dmitri instructed me, the powerful reminiscences of my childhood lessons with my mother began to meld with memories of her reading Nabokov when I was an adolescent, of her own world-within-worlds mirroring of Nabokov’s childhood in a country and a period I had never known. The forests of blue firs by the Caspian sea-lake, the glorious countryside in summertime, her grandparents who time and again had traveled to Russia in the first decade of the 20th century, in another world that appeared as remote and mysterious to her now as it was to be always unreal to me. So that, in the end, several generations seemed to converse through Dmitri and myself during those afternoons—fathers and sons, mothers and daughters, exchanging words and even at times switching parts, as in a luminous labyrinth through which Russia, by way of Iran, had come alive again in the most unlikely of American towns. It felt like a miraculous antiphonal echo to my first English lessons that, years later, a Nabokov was completing my English education.

We had all survived the revolution in our own way. We had created our stories. I had been born in Paris and spent a fraction of time in Tehran. But soon the 1979 revolution swept away time as we knew it. My uncle was assassinated. My grandmother suddenly died. My mother was the final person to be called on the endless waiting list for the last flight out, amid an airport convulsed with fear. That night, the borders were closed. Her cousin walked west through the Kurdish mountains. My father and I had been away and were never to return. I grew up in Paris surrounded by Iranians who only ever talked about their homeland. The things they had seen that I would never see. The ancient cities, the dreamy harbors, the sonorous street names that no longer existed. I created a mental geography, and imagined, likely, another country.

In this, our new reality, my mother became an anchor. She had lost almost everything overnight. Yet her strength was to believe in culture. She wanted me to acquire the one thing that could never be taken away. So we read, listened to music, learned unknown languages. Western literature existed alongside centuries of Persian tradition. Each new discovery brought its modicum of happiness. For an hour or two, exile became a notion rather than a perpetual prickle in the stomach. Space was abolished. And “culture” amounted to no more and no less than a mosaic of stories, where home, at last, was everywhere.

As the days passed, I was still unsure about what Dmitri actually thought of my book. But what had begun as a nervous attempt to garner approval had turned into an exercise in sharing, somewhat ecstatically, with a hawk-eyed Nabokov, the thrill of planting one’s claws into such miniature stuff as stories, and texts, are made on. Until the third night, when following hours of question-and-parry, Dmitri rather matter-of-factly approved the manuscript, and sent off its writer to a life of her own. He was asleep when I left the apartment, and whisked down Ocean Drive, holding fast to the marked-up pages and thousands of words.

Lila Azam Zanganeh was born in Paris. She has taught literature, cinema, and Romance languages at Harvard University. She now writes and lives in New York City.