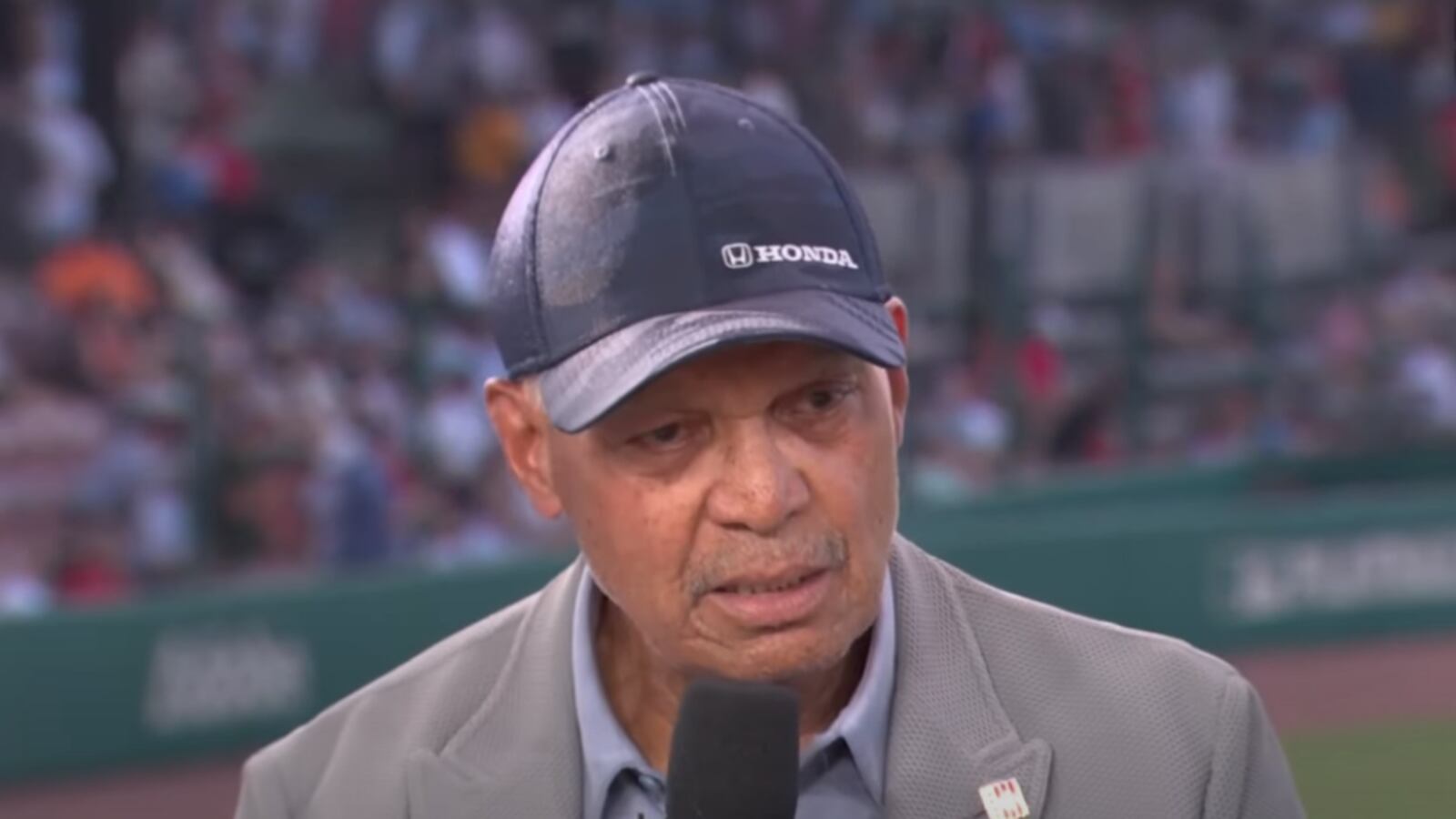

Baseball legend Reggie Jackson on Thursday evening returned to the historic Alabama park that helped launch his Hall of Fame career. He sat down with Fox’s broadcast crew and delivered a powerful monologue about the ugly racism and bigotry he endured there in the 1960s.

During the MLB’s Negro League tribute game between the St. Louis Cardinals and San Francisco Giants, Jackson bluntly recounted his time playing for the Birmingham A’s before he was called up to the majors in 1967. At the time, Jackson noted, he was one of the few Black players on a team that played in the Deep South as it emerged from Jim Crow.

“Coming back here is not easy,” Jackson said before the game. “The racism when I played here, the difficulty of going through different places where we traveled. Fortunately, I had a manager and I had players on the team that helped me get through it, but I wouldn’t wish it on anybody.”

Appearing emotional at times, Jackson said that even though people may say now that “you won when you played here and conquered,” he “never” would want to relive that time in his life. “I walked into restaurants, and they would point at me and say, ‘The n***er can’t eat here!’ I would go to a hotel and they’d say, ‘The n***er can’t stay here!’”

The five-time World Series champion credited his Birmingham teammates, manager, and the A’s team owner for their solidarity in coming to his aid at the time. Jackson spent much of the season with the Double-A squad before being called up to the Kansas City A’s later in the year. The team would then move to Oakland the following season, where Jackson would win three consecutive world championships and establish himself as one of baseball’s premier sluggers.

“We went to Charlie Finley’s country club for a welcome home dinner, and they pointed me out with the N-word. ‘He can’t come in here!’ Finley marched the whole team out. Finally, they let me in there,” he said.

“Fortunately, I had a manager in Johnny McNamara that if I couldn’t eat in a place, nobody would eat. We’d get food to travel,” Jackson added. “If I couldn’t stay in a hotel, they’d drive to the next hotel and find a place where I could stay.”

The former MVP, who was known as “Mr. October” for his postseason exploits, also recalled receiving death threats while playing in Alabama at the height of the civil rights movement.

“Finally, they were threatened that they would burn our apartment complex down unless I got out,” he exclaimed. “I wouldn’t wish it on anyone! The year I came here, Bull Connor was the sheriff the year before, and they took minor league baseball out of here.”

He concluded: “I wouldn’t wish it on anyone. At the same time, had it not been for my white friends, had it not been for a white manager and [Joe] Rudi, [Rollie] Fingers, and [Dave] Duncan and Lee Myers, I would have never made it. I was too physically violent. I was ready to physically fight someone. I’d have gotten killed here because I’d have beat someone’s ass and they’d have hung—you’d have seen me in an oak tree somewhere.”

Billed as the oldest professional ballpark in America, Rickwood Field was home to the Negro Leagues’ Black Barons, which once featured Hall of Fame icon Willie Mays on its roster. Mays, who died on Tuesday, was honored during festivities before Thursday’s contest.