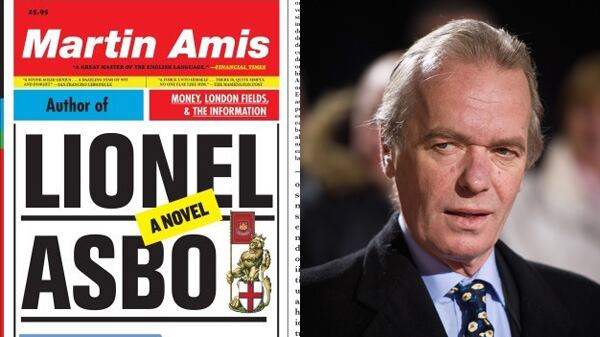

Martin Amis—whose latest novel, Lionel Asbo, has just been published—may be suffering from Norman Mailer syndrome. Like Mailer before him, Amis has given so many loose-lipped interviews and been the subject of so many gossip-filled profiles that people who have never read Amis have opinions of him.

And like Mailer, Amis was at first lionized by the media, then caricatured, and then vilified. In Amis’s case, the unforgivable sins are: getting a divorce, switching agents, receiving a huge advance, fixing his teeth, moving to Brooklyn, and being the immensely talented, physically attractive son of a famous writer. Amis’s penchant for making provocative comments that feed the media’s endless appetite for outrage is also at play. Like Mailer, Amis’s ironies are often misunderstood.

But none of that matters, really. The books do. So, how to choose the essential Martin Amis?

Best to go with the fecund middle period, three novels sometimes referred to as “The London Trilogy.” Begin with Money, a hugely entertaining chronicle of ‘80s excesses, in which Amis found his mature voice, much in the way that his literary hero Saul Bellow came into his own in The Adventures of Augie March.

Money’s protagonist is John Self, a hard-drinking, wild-man British director of TV commercials who is making his first feature film in America. Crossing the Atlantic to set his story largely in New York liberates Amis to range exhilaratingly through American society where John Self senses “all the contention, the democracy, all the italics, in the air.” And though the atavistic Self is the narrator of his own self-destructive tale, Amis finds increasingly poignant dark beauty in this headlong bender of a novel.

Amis next managed to follow his own very tough act. London Fields features Nicola Six, one of Amis’s femme fatales. The wildly attractive, somewhat cartoonish Six is even more self-destructive than John Self: she deliberately plots her own murder, stealthily recruiting an upper-class twit and a classic Amis yob in her conspiracy of self-annihilation. The yob, Keith Talent, is one of Amis’s finest comic creations, a porn-addicted, failed criminal who dreams of being a champion darts player. The twit, Guy Clinch, is the unlucky father of Marmaduke, an 18-month-old prodigy of domestic mayhem. London Fields takes place while London itself is experiencing some sort of vaguely defined “global crisis,” and Nicola Six’s behavior mirrors our self-imposed, late-20th-century nuclear and environmental woes. Perhaps the novel at times strains for the sort of significance that flows more effortlessly from Bellow’s many high-minded protagonists, but the audacity and freedom of the narrative—and the sheer pleasure of reading Amis’s sentences—are the real attractions here.

Novels about novelists can be a claustrophobic mix of self-pity and self-praise, especially if the novelists in question are middle-aged and increasingly aware of their own mortality. But Amis escapes these traps in The Information, the story of two lifelong literary friends dedicated to covertly trying to destroy each other. They’re novelists, after all—and this is a Martin Amis novel—so what really do you expect besides jealousy, envy, adultery, and the like? The absurdly successful Gwyn Barry is a hilarious take on middlebrow, narcissistic celebrity authors. Barry’s old friend, the wildly unsuccessful Richard Tull, is a “marooned modernist” whose tortured fiction has literally sent readers to the hospital. The Information is a devastating comical take on the price of unrealized literary ambitions and the desperate acts that failure can inspire.

Special mention also goes to The Moronic Inferno, Visiting Mrs. Nabokov, and The War Against Cliché, collections of Amis’s witty—sometimes generous, sometimes brutal—profiles and literary essays.

Read the books; ignore the hype.