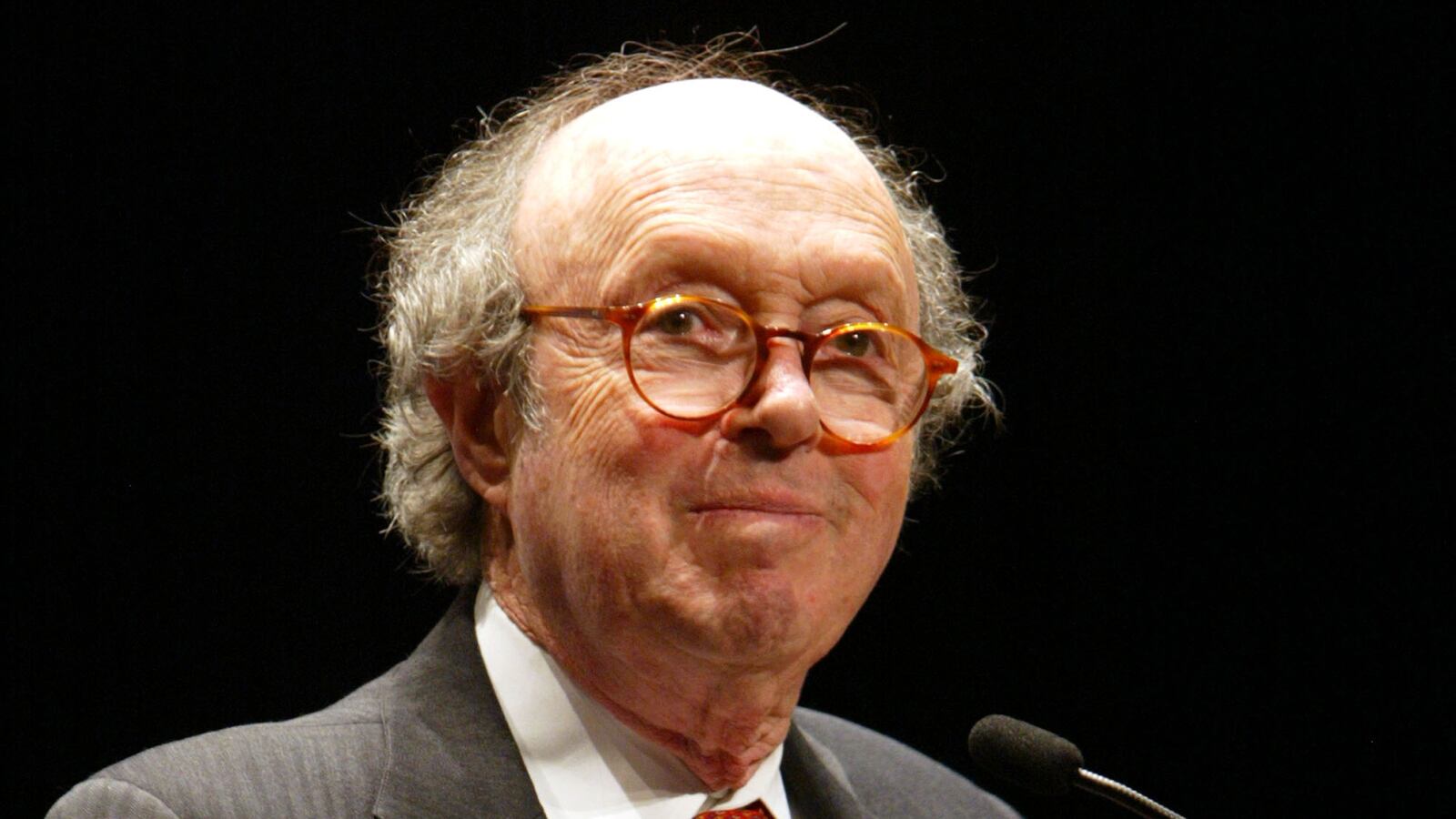

I was privileged to know Anthony Lewis for 50 years. My wife and I named our son Gideon after Tony had sounded Gideon's Trumpet. Tony encouraged me when I first called for a British Bill of Rights and felt alone. He came to Strasbourg, France, to witness the free speech argument in Harry Evans's landmark thalidomide case. His commentary on the American Supreme Court in good times and bad times, for which he won his second Pulitzer in 1963, was worth a hundred textbooks. He was a wise and balanced reader of the First Amendment.More than that, Tony was a mensch who lived life deeply with his best beloved Margie, the brave, brilliant, and gorgeous former Chief Justice of Massachusetts who cherished him and made him wholeWe will not see his like again and will always remember that gentle and well-tempered master writer and loyal friend.

If there is a heaven, Tony will surely enter to the sound of God's trumpeters.

*****

The Essential Anthony Lewis Reading List, by Josh Dzieza

Abraham Chasanow

Lewis won his first Pulitzer in 1953, at the age of 28, for a series of articles on Abraham Chasanow for the Washington Daily News. Chasanow, a Navy clerk for 23 years, was suspended from his job for alleged Communist ties but forbidden from knowing the names of his accusers. Lewis’s articles brought national attention to Chasanow’s plight, and the Navy, embarrassed, reinstated him. In an obituary for Chasenow in 1989, Lewis wrote:

All that may seem like ancient history, but it is not. American law, particularly our immigration law, still has provisions allowing officials to make decisions vitally affecting people's lives without giving them a fair chance to test the truth. The American press is stained by too many examples of the deadly anonymous accusation. Any society, however committed to law, has to be reminded again and again that it is deadly to reach conclusions on secret, untested evidence. From the French Revolution until today, the accuser has used the shield of anonymity to work off grudges and hatreds. In secrecy, there cannot be truth.

Baker v. Carr

Lewis, now covering the Supreme Court for The New York Times, won his second Pulitzer in 1963. The Pulitzer committee mentioned Lewis’s coverage of Baker v. Carr, a legislative districting case in which Lewis’s own writing was cited in the decision.

The next year, during a newspaper strike, Lewis wrote Gideon’s Trumpet, a book about the case of Clarence Earl Gideon, a Florida drifter who had been convicted without a lawyer. The decision guaranteed lawyers to poor defendants, and Lewis believed it was part of a trend in the Warren court of expanding the definition of civil liberties. In a 2003 piece for the Times, Lewis revisited the principles of Gideon v. Wainright and found the current legal system wanting:

Why does the dream of the Gideon decision -- the dream of a country in which every person charged with crime will be capably defended -- remain just that, a dream? Why do judges countenance mockeries of legal representation? Why do we, the citizens, tolerate such unfairness?

Freedom of Speech

Lewis was a nuanced scholar of the right to free speech, describing the implications of the libel case New York Times Co. v. Sullivan in his book Make No Law, and tracing the legal evolution of the First Amendment in his last book, Freedom For The Speech That We Hate: A Biography of the First Amendment. But Lewis was occasionally at odds with his fellow journalists, frequently arguing against journalistic privileges like the right to protect confidential sources and high standards for libel suits. While Lewis supported a press that could harshly criticize government officials, he worried that insistence on special journalistic rights would create a media that was arrogant about invading privacy. Invoking the case of Wen Ho Lee, a government scientist who, echoing Chasanow’s case, was accused by anonymous sources of being a spy from China, Lewis wrote:

Suppose that a federal shield law had existed when Wen Ho Lee sued to seek some compensation for his nightmare ordeal. The journalists who wrote the damaging stories would have had their subpoenas dismissed, and without the names of the leakers Lee would probably have had to give up his lawsuit. Is that what a decent society should want? Would that have really benefited the press? Or would it have added to the evident public feeling that the press is arrogant, demanding special treatment?