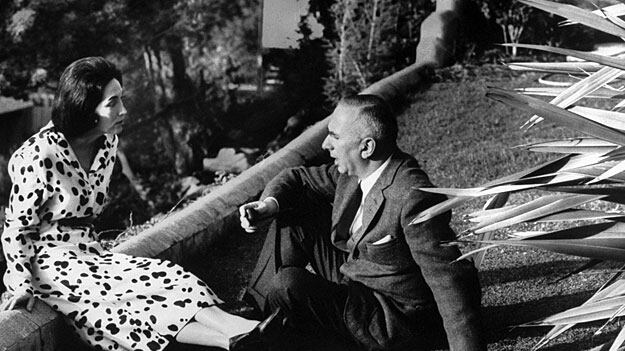

In 1959, just three years before Helen Gurley Brown famously authored the bestselling Sex and the Single Girl, she married David Brown, years before the producer would come into his own professionally. But David was the one who famously encouraged his new wife, who was a not-so-girlish 40 at the time, to chronicle her bachelorette days in what was to become a tome for female sexual empowerment. “Having a man is 50 percent of living,” the famed relationship adviser later wrote at the magazine she shaped.

Allan Grant, Time & Life Pictures / Getty Images

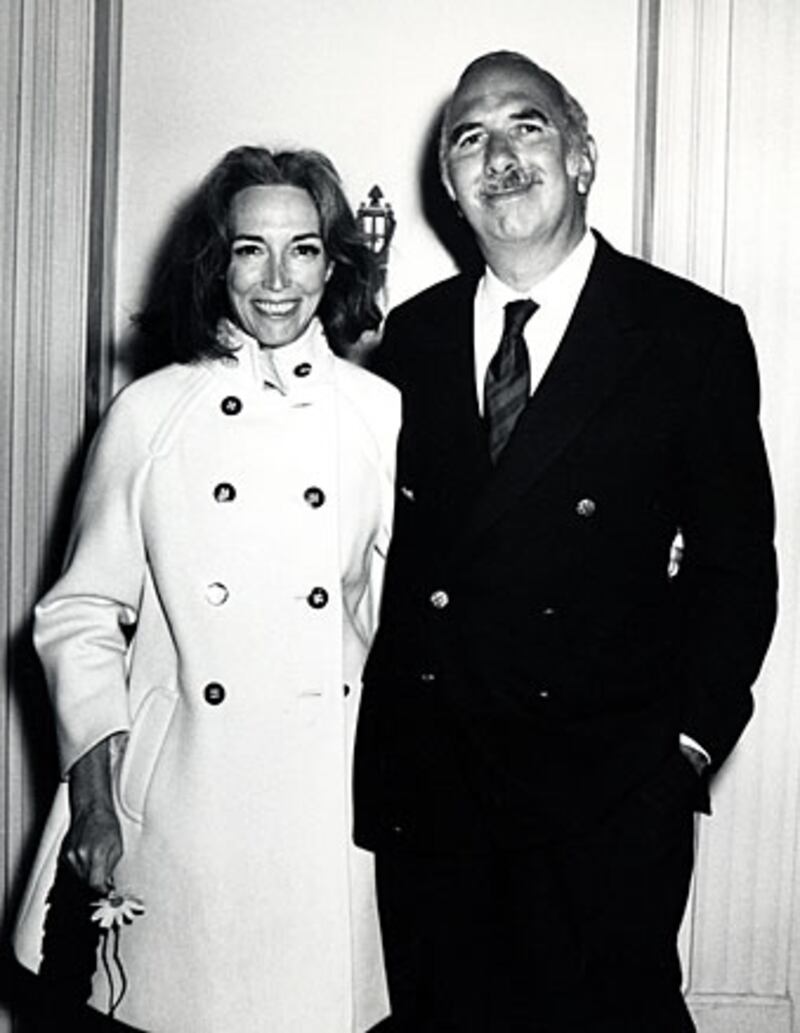

When Helen, who had never worked as an editor before, was approached to helm the struggling Cosmopolitan in 1965, it was again her husband who stood behind her as she invented what we now know as the women’s magazine. Her formula combined curvaceous cover models with provocative headlines, some of which her husband would reportedly write. “The Startling Truth About Sex Addicts,” “How To Be Very Good In Bed,” and “The Terrible Danger of a Perfect Sex Partner,” are all courtesy of David, according to AP. He also edited her personal column in Cosmopolitan, “Step Into My Parlor.”

Ron Galella, WireImage / Getty Images

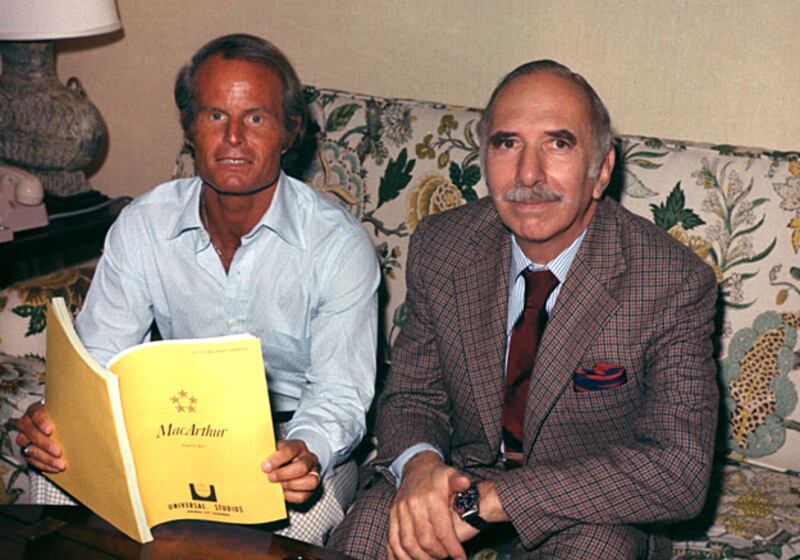

When Zanuck’s father hired Brown in 1951 to head the story department at his studio, 20th Century Fox, he could not have predicted the eventual executive would leave to team up with the younger Zanuck in 1972 to create their own production company, as reported by The New York Times. “He had a great story sense,” Zanuck said, “and great connections with publishers and agents.”

Universal / The Kobal Collection

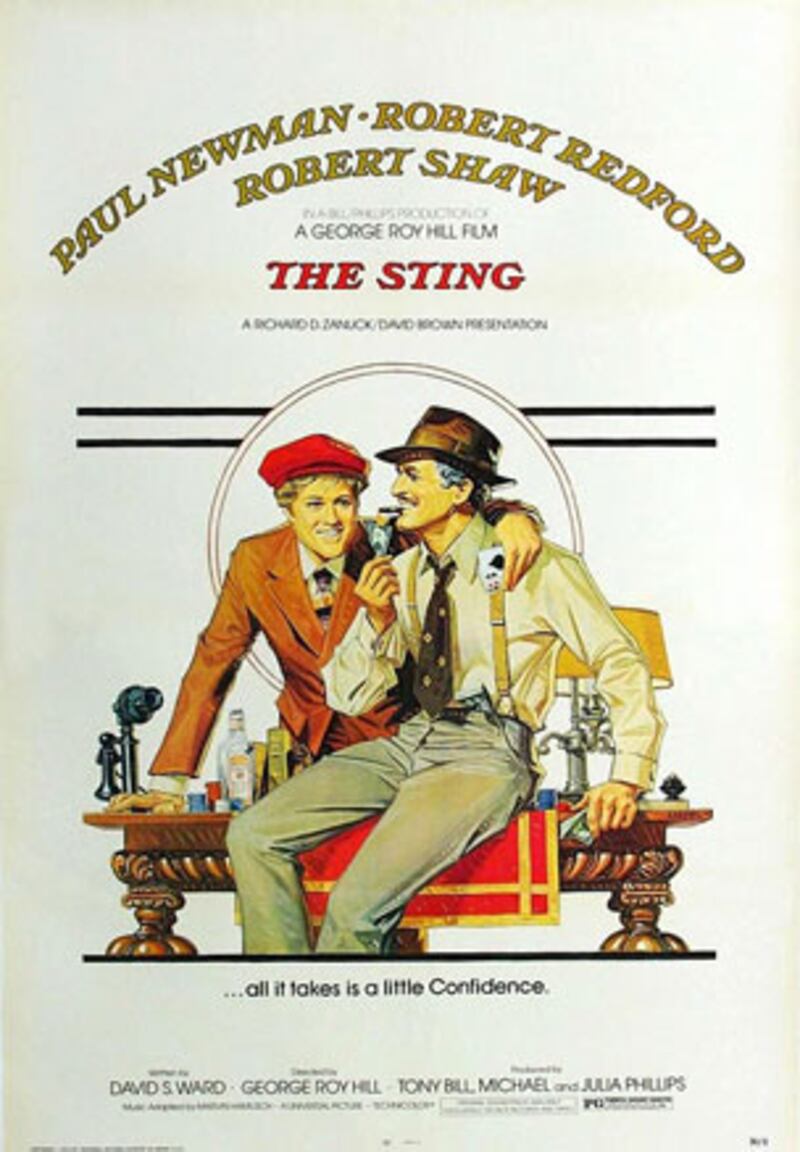

The year after Richard Zanuck and Brown teamed up, one of their first films, The Sting, opened to immense critical success, earning seven Academy Awards, including Best Picture. Though the pair was not credited as producers for the Paul Newman and Robert Redford caper, the movie was identified as “a Richard D. Zanuck-David Brown presentation.”

As Brown began breaking into the film industry, he and his Cosmo girl became a power couple on the New York social scene. At the 1977 West Point Society benefit premiere of his film, MacArthur at the Waldorf-Astoria, the pair was still in love after nearly 20 years of marriage. “The extraordinary thing about Helen is that she's so unpredictable,” Brown told The New York Times in 1995. “I’ve never had a boring moment with her.”

Bettman / Corbis

After Zanuck and Brown produced the megahit Jaws in 1975, the two continued to have big-screen success. In 1985, audiences and critics alike were wowed by their fantasy film Cocoon, a Ron Howard-directed story of senior citizens who stumble upon evidence of alien lifeforms in a swimming pool that ends up serving as a fountain of youth. “He knows that story drives everything,” Howard told Variety in 1998. “He loves writing, and he know what ideas will translate and what won’t.” The film went on to win two Oscars and became a classic in the sci-fi genre.

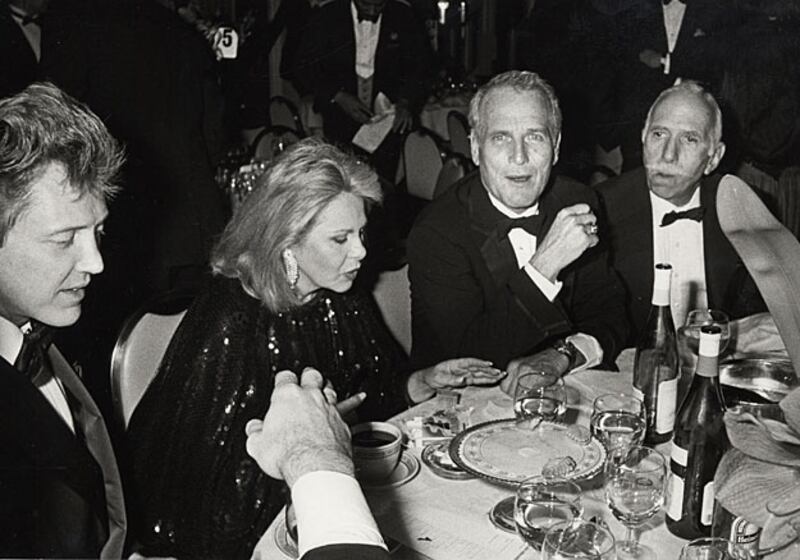

In the ‘70s and ‘80s, Brown became a mainstay at Hollywood events. When the American Museum of The Moving Image saluted Sidney Lumet in 1985, Brown sat amongst actors Christopher Walken and Paul Newman, as well as former talent agent to some of the most important members of the movie world, Sue Mengers. “At a certain age you become cool, not cold,” he told The New York Times in 1999. “I kind of represent the new and old Hollywood.”

Ron Galella, WireImage / Getty Images

When Zanuck and Brown’s professional relationship amicably dissolved, the latter proved successful going it alone. He earned his second Best Picture Oscar for his adaptation of Alfred Uhry’s Pulitzer Prize-winning play, Driving Miss Daisy in 1989. But producing, he told The New York Times, is a thankless task. “When people look at credits on a movie, like gaffer or camera assistant, they know what they do, but the problem is no one quite knows what a producer does,” he said. “Actually, the producer is the first one on the project and the last one off.” In Brown’s acclaimed ‘50s-era film, Jessica Tandy played Miss Daisy, a Jewish widow living in Atlanta who is forced in her old age to hire a driver. Morgan Freeman reprised his role from the stage production as the driver, Hoke, who shares 20 years with the movie’s title character.

Taking on another adaptation, Brown brought Angela’s Ashes, Frank McCourt’s chilling memoir of his poverty-stricken childhood in Limerick, Ireland, to the big screen in 1999. “Whatever Frank writes,” Brown, who bought the rights to the book with co-producer Scott Rudin, told Entertainment Weekly, “Scott and I will be first in line [to buy it].”

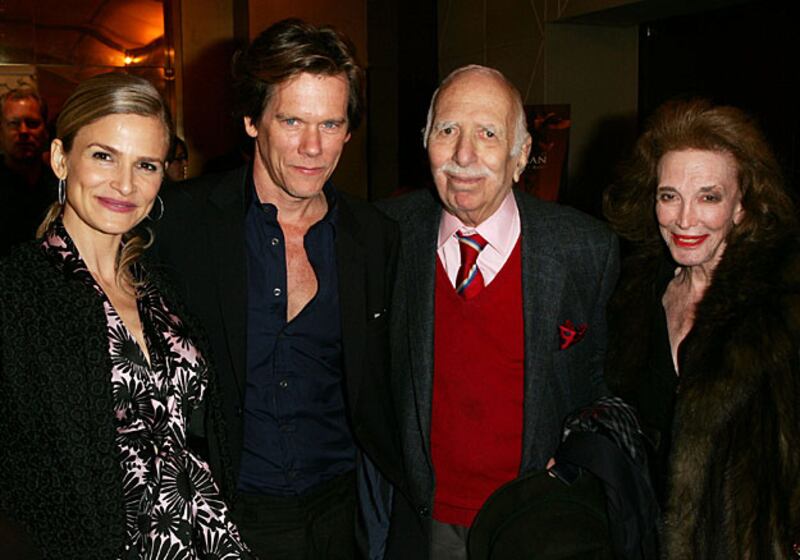

Even after 45 years of marriage, David and Helen Gurley Brown were still as in love as younger Hollywood couple Kyra Sedgwick and Kevin Bacon at a special screening of The Woodsman in 2004 in New York City. Three years ago, the couple told USA Today that Brown would write his wife a poem on Valentine’s Day, her birthday (four days later), and their September 25 anniversary, all of which she kept in a leather folder by her manual typewriter in their Upper West Side apartment. One from February 14, 1999 read: “For nearly 40 years / of love and laughs and, yes, tears / you have been mine, Valentine.”

Peter Kramer / Getty Images

Now that he’s gone, the industry’s top executives and filmmakers have emerged to shed light on the talented and magnetic David Brown. “His expansive body of work will be enjoyed by people around the world for many centuries to come,” said CEO of Hearst, Frank A. Bennack. “He will be greatly missed.” And never will he be duplicated. “He was the last great gentleman producer,” said writer/producer Aaron Sorkin, whom Brown discovered. “You’re not going to see his kind again.”

Amy Sussman / Getty Images for the Israeli Film Festival